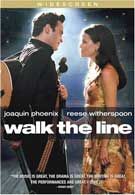

It used to be telling the story of a celebrity’s life was material for the Sunday night movie on one of the three networks. Now it’s almost a basic requirement for a movie to receive any Oscar nominations. But how could anyone beat 2004’s successful take on the life of the soulful Ray Charles (starring the unlikely Jamie Foxx)? Easy – stop making the movie about the celebrity and focus on the person behind the legend instead. It wasn’t long ago that I not only wasn’t a fan of Joaquin Phoenix, but that his presence in a film was enough to turn my interests away. I felt his performance in the overhyped Gladiator was extremely poor, spouting speeches and gesturing like an actor of the stage in Shakespeare’s time, not a Hollywood actor in front of a camera. If any doubts about Phoenix’s ability still remained by the time Walk the Line got here, they’ve been erased forever, wiped away by a performance as the legendary Johnny Cash that shows the legend and the man within.

Phoenix’s performance as Cash is flawless. Although he manages to capture the feeling of Cash’s baritone voice, Phoenix doesn’t perform an absolute mimicry of the former music star, instead he evokes enough of Cash for us to recognize who this character is, and then takes control of that character. The true testimony to his performance is not when Phoenix is speaking, but when he’s reacting, just watching his face as words come out of the mouths of Cash’s first wife Vivian (Ginnifer Goodwin), who opposed Cash’s musical career, or June Carter (Reece Witherspoon), who Cash loved from a distance for many years.

It is those relationships, rather then Cash’s career, that take center stage for Walk the Line. Sure, the movie shows lots of performances by Phoenix and Witherspoon as Cash and Carter, but those songs are a loose framework for the true heart of the story – a man and a woman falling in love. By centering the film around their relationship, the movie allows Phoenix and Witherspoon to give some brilliant, heartfelt performances that people can relate to.

The same is true of several other performers, like Robert Patrick, who plays Cash’s disapproving father over the course of twenty years, a performance, along with Ginnifer Goodwin’s disapproving Vivian, that drives the second plot for Walk the Line: Cash’s attempt to find acceptance for what he does, both from his family and from himself. The movie doesn’t let the audience forget that all of this took place in another time, when music from stars like Cash or Elvis Presley wasn’t widely accepted, viewed by some as flat out evil. Evil music like theirs led to drug use and divorce, which was also frowned upon. All of these are elements woven in and out of the movie artistically, making Cash’s story almost a modern-day fairy tale. We want Cash to beat all the bad guys (his naysayers) and get the girl in the end.

Maybe that’s what makes Walk the Line work better than most bipoics out there – it appeals to the average moviegoer by making Johnny Cash look incredibly human. This isn’t a movie about a superstar or a legend; it’s a story about a man, with faults, dreams, and desires just like anyone else. It’s about friendship – the kind of friendship that stays with a person through the good and bad, and eventually blossoms into a beautiful love. Thanks to the excellent performances, direction, and script, the audience pulls for Johnny to make it, despite the fact that we already know he does. Walk the Line is the latest in the trend of separate one and two-disc releases. The version you want to pick up depends entirely on your interest in the film and the actual life of Johnny Cash. The two disc edition includes extended musical performances by Phoenix and Witherspoon (undoubtedly full versions of the scenes that appear in the movie), an extended documentary about Cash and the making of Walk the Line, and featurettes about Johnny and June Carter’s romance and the historical concert at Folsom Prison.

Sadly, that wasn’t the version we were given to review.

Instead we’re looking at the single disc edition, which actually makes up the first disc of the two-disc set. Knowing there’s a better version of this film on DVD is automatically a strike against this release for me. I almost always want the best DVD release I can get, and studios releasing separate versions for collectors like this seems contrary to the entire spirit of DVD to me.

The movie itself is fantastically transferred to DVD. This is the type of movie that really pushes a home theatre, particularly the bass sound of Cash’s music. In order to truly appreciate the film plan on turning your sound system up and taking the phone off the hook so the neighbors can’t complain. If the police haven’t been called, you’re not watching this movie properly.

There are ten deleted scenes included, with optional commentary by director James Mangold. Most of the scenes are short sequences that make complete sense to have on the cutting room floor, but there are one or two scenes that feel like a shame to see cut. Particularly of note is a scene where Johnny breaks the demo record he cuts early in the film and calls the record company producer in a panic, only to discover that was just a test press and the producer has a thousand copies of the record. It’s a moment similar to the first time the band hears their song on the radio in That Thing You Do!, one of the moments this movie was missing by not focusing strictly on Cash’s music career. It’s a really good scene, one that I will miss now that I know it existed. I can understand why it was cut though – most of the really good deleted scenes add more separation to the relationship between Cash and his first wife, Vivian. Since she’s already depicted in the film rather wickedly, that part of the story didn’t really need any more help. In fact, the addition of these scenes might have even taken her character too far.

The other main feature for the disc is a commentary by Mangold, a director who offers some great insights as to how he goes about making a movie. Mangold opens the commentary by reading what he had written in the script for the film’s opening. It quickly becomes apparent how much of this movie was in Mangold’s head before it ever touched film, and how true the film is to that version. For that reason alone Mangold deserves a lot of credit for Walk the Line’s success. The only complaint I have about Mangold’s commentary is the mixing of it. When Mangold gets silent (which isn’t very often) the movie volume comes blaring back up. There’s no fading in or out of the movie’s audio – it’s either on or off, which is a bit annoying, although not enough to keep me from listening.

If the single disc release is any indication, the two-disc release for Walk the Line is the one worth getting, after all, it can only improve on what is already an excellent DVD release. If I were picking up one of these editions (which I highly recommend), that’s where my money would go.

Most Popular