There’s only so much you can do with a movie like 127 Hours. Director Danny Boyle does all of it, but in the end his film still hinges almost entirely on the performance of James Franco. Franco is an actor who, till now, always tried hard but never really achieved anything beyond mediocre results. An enthusiasm for acting, a willingness to take on challenging projects, and movie star good looks were always there, but talent? Until now I’d never really been sure. But in taking on the true life story of trapped climber Aron Ralston, Franco finds himself in the perfect place at the perfect time. It’s a role which. if played by someone else, might have just been the story of some guy trapped in a hole. Franco finds something more.

James Franco plays Ralston as a geek, and like all geeks he has an obsession. His obsession isn’t collecting Star Wars figurines or vintage comic books, his obsession is the outdoors. An engineer by profession Aron dreams of making his living as guide and when we meet him, he’s home from work and packing up for a weekend to be spent under the stars and sun, wandering endless, remote canyons all alone. He’s confident in his abilities, perhaps with good reason, and so he doesn’t bother to tell anyone where he’s going. Yet even an experienced hiker, his head packed full of survival knowledge, can’t prepare for everything.

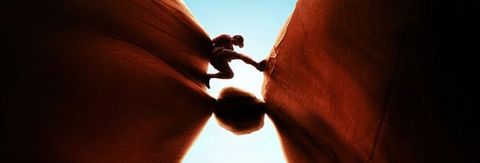

The real life Aron Ralston’s story is well publicized, and by now it’s not a spoiler to tell you that before long he’ll end up trapped at the bottom of a canyon, pinned beneath a rock he can not move. Stuck there all alone for nearly a week, Aron will have plenty of time to think of everything he did wrong. The Swiss Army knife he failed to pack, the Gatorade bottle he left in his truck, the phone call from his mom he didn’t answer as he threw everything in his bag and hit the open road. Eventually he’ll have a choice to make. By the time he makes it, it’s almost not a choice, just a final desperate act to survive at any cost.

We spend a few brief moments with Aron, before he’s trapped, as he races across the wilderness on his bike. On his way out towards solitude he’ll encounter two pretty hikers. They’ll invite him to a Scooby Doo theme party, and fantasizing about what it might have been like if he’d shown up is one of the many things that’ll keep him going during his long imprisonment. Most of the movie is spent there with him, trapped beneath a rock, for 127 hours of solitude. The only thing on screen is Franco’s Ralston, with no one to talk to, nothing to do but sit and struggle and despair. Somehow, Ralston never gives in to panic; he’s too capable, too smart, too savvy for that. That doesn’t mean, however, he has a way out.

A lesser filmmaker would have blanched at the prospect of spending an entire movie in one place, with one character, and nothing to do but stare. At least in Cast Away Tom Hanks had an island to wander around and a beach ball to talk to. A lesser filmmaker would have panicked and cut away, perhaps to show us a rescue effort underway, or to fetishize his grieving family. Danny Boyle never does. He doesn’t need to, James Franco’s performance, sitting in that one spot, is that good.

Instead Boyle tries to find meaning in Ralston’s predicament. Aron sits and fantasizes about the choices he’s made and the people he loves. In more than one, feverish fantasy Ralston envisions himself freed and moving on. Some of these fantasy sequences are more successful than others. None of them are as good as the moments in which we simply sit with Franco, underneath that rock, and stare into the heavens looking for hope. None of those moments are as thrilling as his tiny triumphs of improvisation, his steely-eyed determination to find a way out, the minutiae of minute by minute life turned into grim life and death decisions. Much as he tries I’m not sure Boyle ever really finds that broader meaning he’s looking for. There’s some attempt to make a point about the way we’re all connected and how much we need each other, or to make a statement about the power of the human spirit. Some of that feels forced. It’s one man, in a hole, he does what must be done in order to survive, and that’s enough.

Franco’s best moments are almost entirely silent. The one that’ll stick with me, perhaps forever, comes after he’s finished the grisly, horrifying work of freeing himself. Aron stumbles back to survey what he’s done and for a moment, just a moment, there’s a smile. Standing there bleeding and dying, he steps back and grins, it’s the grin of someone who never thought he’d leave one spot and, no matter what happens from there on out knows he’s already won. His dirty, bloody, crooked smile in the face of unexpected freedom says everything there is to know about what’s happened and what matters most to Aron in those terrible moments. It’s a masterful performance by Franco, sharply directed with all the visual flair he can bring to bear on a single location by an unflinching Danny Boyle. 127 Hours is the kind of movie you absolutely must see once and then, battered and broken by enduring Ralston’s gruesome predicament with him, you’ll never want to see again.

Most Popular