Interview: Benjamin Bratt

I realize I’ve confessed to having a crush on interview subjects before, but I promise, Benjamin Bratt’s interview below is not so long because I dig him. He’s really just that well-spoken, and not unlike his character in Love in the Time of Cholera, the handsome doctor Juvenal Urbino, whom Bratt himself describes as “Superman” Still, just as Lois Lane loved another, Juvenal is not the right man for his wife, Fermina Daza (Giovanna Mezzogiorno), who is loved from afar for 50 years by Florentino Ariza (Javier Bardem). Though he spends the film in the middle of an epic love, Bratt still took some lessons on the subject from his work in the film, as well as how the right outfit can turn a man into an ocean liner.

You’re playing a good man in this film who is still the wrong guy. He has his flaws, but he’s still a great man.

The initial challenge is he’s damn near the perfect man. As described in the book he’s everybody’s dream, from every bachelorette who lives in Cartegena to various artists that he’s a benefactor to. He’s learned, he’s worldly, he comes from a great family, he’s wealthy, he’s charming, he’s good-looking, he’s a doctor, he’s a patron of the arts, he solves the problem of cholera. He’s Superman. The way Mike described it, and I love this description—actually it was quite helpful for me as I tried to portray him—in addition to all of those qualities, he’s extra kissed by God. He’s someone who’s lived the luckiest of lives. Yet as you say, he is not without his flaws. That’s what makes him really so interesting I think. His approach to love is a practical one, just as his approach to life. When he meets Fermina Daza it’s clear that he’s struck by this thunderbolt of lust for her, and it leas to marriage, but even after he marries, as it’s pointed out in the book, he’s not in love with her. But he knows that there will be little obstacle to actually achieving a kind of love. Not terribly romantic, as I said. And in the other part of the love triangle you have someone who operates only from a place of heart-driven emotions, a place of passion. I think the fact is, and the story kind of demonstrates, that there’s a balance of the two that ends in some form of real love.

Why do you think he marries her? You said he didn’t really love her, but he was pursuing her.

Yes, he was pursuing her. As was the case in a lot of marriages, even contemporary marriages, it’s because she’s a good match. He likes her haughtiness, he likes her strength. There’s a part of it that appeals to his vanity. She’s clearly beautiful. That’s described aptly in the book.

But there was no love on his part?

It’s not that he didn’t like her. I think he liked her quite well, it’s just that he wasn’t in love with her at the time of marrying her. The book clearly illustrates that after their time in Paris together—they spent two years on their honeymoon—it has become a kind of love. But again, not really romantic, is it?

CINEMABLEND NEWSLETTER

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

Would you consider it a failed marriage at all? They’re together a long time, they have a large family…

I wouldn’t consider it a failed marriage at all, nor would they. In fact she says at the end of the book, at the end of the film, it was a great marriage, he in fact was a great husband. It was filled with happiness. But the question she ponders is, ‘Was it ever really love?’ I think that’s a mistake that we really all kind of make, we equate happiness with love. How familiar with the book and Marquez’s work were you going into this?

I was extremely familiar with the title, so much so that I mistakenly thought that I had read the book. I’m of an age where it would have been apt for me to have read it when it came out in the mid-80s, but after page 2, I realized that this masterpiece certainly would have made an indelible impression on my mind. It’s quite easy to fall in love with him, though. I think he’s a genius. In this meditation on love, to me he demonstrates the most astonishing understanding of love in all of its different forms. The book is about romantic love, but it’s also about familial love, patriarchal love, maternal love—there’s all sorts of different love that’s explored here. The depth of his understanding just blows my mind. He has me laughing on one page and crying on another. The hope of the filmmakers, and their great challenge really, was to capture the essence of the book. The challenge was made all the greater because it’s one of the most well-known and beloved books on love ever written. I feel pretty confident they actually succeeded.

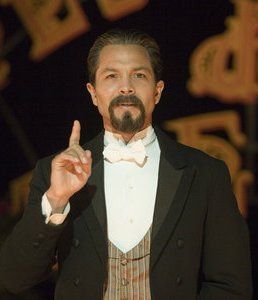

How did the costumes, the facial hair, everything help you get into character in this film?

It’s everything, really. There was a lot of homework that goes into portraying someone like this. He’s so far removed from who I am as a person. I’m not an aristocrat, I have no idea what that is. So we employed a lot of things to get to that stage. One thing that was incredibly helpful was to have a movement instructor come down, to help us not just with the old age, but with the actual development of the carriage of this person. We would work with images. For me the line was ‘The purity of elevation,’ so everything I did was to make it to feel extended, to kind of indicate an un-self conscious sense of privilege, something that you’re born into, that you don’t even question. All the other accoutrements helped inform it from a visual perspective. I read somewhere that Olivier never really felt like he was the character until he literally walked in the shoes of the character. It’s a similar thing. When you’re wearing a vest and a tie and this long, beautiful coat that’s essentially taped to the ribs, and a top hat, you can’t help but feel like some kind of ocean liner, steadily cutting through the rough sea. Nothing perturbs you whatsoever, it’s pretty remarkable. Then the walking stick and everything else—it’s certainly not walking around in a hoodie and jeans. You get in an altogether different physical state.

You and Javier didn’t have many scenes together, but your characters develop a lot in relation to the other. Did you work together to create that relationship?

We became great friends, and it was one of our big regrets, that there wasn’t more to do with one another. The one scene that we had together, we relished. We had a great time doing it. It’s [Juvenal and Fernando’s] distinctive approaches to the same woman that make it compelling to watch. That’s a great character; I think he’s really done a phenomenal job at it. Giovanna too. I’ve seen it twice—the final cut was just last week—and the subtlety that each of them employs in their portrayals is really, really lovely.

Is it almost a fool’s errand to try to do justice to a classic book on film?

It can be considered by many to be foolhardy, especially when you’re messing with what’s considered a sacred text. But it’s also an irresistible challenge, isn’t it? It evokes so many different wild and outrageous and beautiful images that anyone who loves both novels and films can’t help but imagine what it would look like on the big screen. In this case I’m glad they took the challenge on. I think Marquez is glad too. Apparently he’s seen it and he’s responded favorably to it, he likes it. The trick is, as you aptly point out, is how to do it but how to do it well. Because it’s not an easy translation to make, and certainly nearly impossible when you’re talking about a great novel, which this is. The best you can hope for really is to capture the essence of the book, and I think the film has done that, which is good news.

What are the different satisfactions in doing film, television and theater? Film and television essentially feel the same when you’re doing it, because it’s the same technical approach. All the homework is the same. The homework for each medium is all similar, but the gratification in a live theater context is much higher, because it’s immediate. It’s far more dangerous, because there are no retakes. It’s electric, it’s an actual chemical transaction that occurs between you and the audience. Whatever energy you’re throwing out to them they throw it right back to you, and it kind of feeds on itself in this vacuum. Film’s not really like that. I think film and television actually is a lot harder. Acting onstage is physically more arduous, but to get to emotional truth within a scene, it’s much tougher to do it on film. Typically you’re sitting in an air-conditioned trailer and you’re bored off your ass waiting for them to get the lighting done. Then they call you and say ‘OK, cry, your daughter just died.’ That’s a tough thing to do. You’re also carrying to that scene and that day and that moment the fact that you got up on the wrong side of the bed, you had an argument about who has to make the coffee with your wife. But that’s the job. They say acting ain’t for sissies…

Had you been to Colombia before?

I had actually been to Cartegena before, with Taylor Hackford and Helen Mirren. We were down there with his film Blood In, Blood Out about a dozen years prior. But it was a brief stay. But having a greater span of time there to get to know the place and get to know the people—it’s a magical, magical place. I think everyone who was a part of this endeavor fell in love with it. […] There’s something really sensual about it. You can feel the history there—it’s a walled city. A lot of the architectural integrity of the place is very much intact.

What did you and your co-stars do when you weren’t working?

Invariably we’d break up into groups and have dinner together. The place thumps and thrives on music and food and the enjoyment of life, even in the face of hardship, and there’s a lot of hardship down there. The disparity between the wealthy and the poor is great, but even in the face of that there’s an acknowledgement of the joys of life. That’s pretty infectious. It’s hard to be glum down there.

How do you balance being a good dad and being a good husband?

In real life? Little sleep, faultless dedication, willpower and the love of a good woman.

And what do you love about your wife [actress Talisa Soto]?

What do I not love about her? She is heart and soul personified, really. She makes me a better man—that sounds like a line from a movie. That is, right? It’s hard not to speak in clichés about her. So much has been made of my wife’s outer beauty, and she is otherworldly beautiful, but as I’ve come to know her, her heart, who she is as a person is even more beautiful. What I dig about her is she loves me even though she knows everything about me. She accepts me anyway. It’s a pretty calming influence to have you in your life, and a great deal of support.

What did the college fraternity experience mean to you?

You’re budding youth, you know? You try things out to see if they fit, and if they don’t you jettison them. Fraternity life for me really was about cheap rent and three square. At the time, you know, a non-stop flowing keg. That gets old after about the first six months, and I found the arts early in my college years. That really became my passion, and everything else was just part of growing up.

You’re shooting the Che film…

I’m not. The dates didn’t work out. I was shooting The Andromeda Strain, the remake of the film from 1971. Ridley Scott’s company produced it for A&E—it’s miniseries. So the dates didn’t work out.

So what else are you working on?

My brother and I are about to produce a film that he wrote and directed called Mission Love, it takes place in the Mission District of San Francisco. A single father and an 18-year old son. There will be more to talk about in a year when it comes out.

Staff Writer at CinemaBlend

Most Popular