Interview: Cropsey Directors Josh Zeman And Barbara Brancaccio

Freddy, Michael and Jason haunt the big screen and may even sneak into a nightmare now and then, but how would you feel if one of these iconic slashers was the real deal? Both Josh Zeman and Barbara Brancaccio got a taste of just that growing up on Staten Island where the legend of a sadistic mental patient on the loose and a murderous urban legend collided.

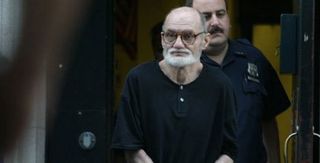

In their documentary Cropsey, the duo combines the scary story of Cropsey with the reality of Andre Rand, a former employee at the Willowbrook State School who allegedly went on a kidnapping and killing spree targeting young victims. Zeman and Brancaccio intertwine their experience with the Cropsey myth and the actual details of Rand’s crimes, giving a face to the fictitious villain. Sit through one of Freddy, Michael or Jason’s films and the bloodshed is over within a couple of hours; check out Zeman and Brancaccio’s and the horror is still very much alive even after the credits roll.

The filmmaking team may not have aimed to make a scary movie, but not only did they create just that, they delivered one far more effective than those consciously made for the genre. Check out what Zeman and Brancaccio had to say about their personal experience with the legend, what their film offers that the news agencies covering Rand’s cases could not and more in the interview below. Also, click here to take a look at a full list of screening dates so you can catch Cropsey at a theater near you.

You both grew up being haunted by the Cropsey legend. Do you remember when you first heard about it?

Zeman: Yeah, I went to a Jewish day camp right on the edge of what’s call Greenbelt and in the middle of Greenbelt was the Willowbrook State School, the tuberculosis ward and the farm colony. So on Fridays we would beg and beg our counselors to take us into these abandoned buildings. We’d find papers, figure out how people died, old rooms and beds and everything and then, of course, out of the closet, one of the counselors would come with an axe and scare the hell out of us that Cropsey was going to get you. From all those events that’s how we first heard of the legend Cropsey and then there was always the urban legend about an escaped mental patient. No matter where you are, no matter what county or what state or what city, there’s always the same urban legend that an escaped mental patient is going to come and get you.

Brancaccio: I first heard the legend of the guy living in the woods when I was a kid. Also, Willowbrook was kind of like in my backyard. It was like a quarter of a mile from my house, so my friends and I would go into the woods and we’d played hide and seek, so there was always that urban legend in areas where there is lots of woods and stuff like that in your backyard. For me it was childhood, just playing in the woods and playing with my friends and later on, of course, when we were in high school, there were parties in the woods. We would go on these little hikes with the intention to kind of scare each other or that sort of thing, so the legend was very much a part of the fabric of that community.

And it’s even way beyond that community. I went to a camp in Pennsylvania and we had a very similar legend.

CINEMABLEND NEWSLETTER

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

Zeman: Right, so this is what’s really cool; the Cropsey urban legend, specifically the name Crospey, started in the 1940s to the 50s in the Boy Scout camps and Jewish sleep away camps of upstate New York, the Catskills and Pennsylvania. Somehow that traveled back down to the city, I guess with the kids coming back from sleep away camp, and then was assigned to the guy who was snatching kids at Willowbrook. So they took a real urban legend, a real campfire story, and they assigned that name to a very real event that was going on.

Was the connection between Cropsey and Rand instant?

Zeman: I don’t think it was instant. We were in two separate worlds. I think it was compartmentalized, you know? And then when we became adults we said, ‘Oh, I wonder if it’s the same thing.’ We were able to intellectualize it and we were able to almost like psychoanalyze it as well. We often said that we can’t corroborate this per se, but the police knew that Andre Rand was operating in the neighborhood and living in the area and so they told the kids, ‘Oh, don’t ever go into Willowbrook.’ To them it was, a killer pedophile lived in the woods. Now, if you’re a little kid and you say, ‘Oh, my dad says we can’t go there,’ you can’t say why and you can’t tell you’re friend, ‘It’s because there’s a killer pedophile in there;’ it just doesn’t sound as exciting. So I think what happened is you’d say, ‘Well … Cropsey lives in there’ and then they were like, ‘Who’s Cropsey?’ and you got to tell the urban legend. So I think in a lot of ways that’s kind of where it intersected. It’s difficult for us to tell what came first, the chicken or the egg? The urban legend or the reality? We know the urban legend was around in the 50s. In fact, are you familiar with the film The Burning?

Nope, what’s that?

Zeman: That was a film, one of the early early slasher films that used the name Cropsey. And it was actually [written] by one of the Weinsteins; it’s one of their first films. And we feel that they went to Jewish sleep away camps in upstate New York and that’s how they got the information.

The press covered Rand’s cases pretty heavily. What were you hoping to achieve in a documentary that the news outlets couldn’t?

Brancaccio: First and foremost, when we went back and looked at all of the pieces, we were able to do something that no one had done so far, which was to put all of the information together. As you know, the pieces went back over 30 years and there was no one police detective that was working on them and there was no continuity at that point. We had the ability, both through our access and conversations with the police officers and also by speaking to all of the members of the community, we were able to piece together all of the information that all these various people had collected over the years. The police didn’t have that opportunity. They were busy looking for the children, they were focusing on the people of interest, but being able to interview neighbors, friends, people that even knew the children, the families and so forth, we were able to put together an entire history of what had transpired and I think, for us too, it was clear that Cropsey and that urban legend was very connected to Andre Rand specifically because we had laid it out and it was clear.

Zeman: I think the news obviously objectively just told the story and for us it was much more interesting to hear it from the personal connection as a Staten Islander because it was a much more richer story when you realized how it effected you and your community. Being able to bring an insider perspective and also, that from a child growing up, to that of an adult processing it is kind of interesting.

Brancaccio: Also, the film is not a straight crime documentary and it’s not a journalistic piece. It’s a film about storytelling essentially. The news was basically covering the events of the day, and our film, while we wanted to add a comparative component to it and basically talk about these cases from the perspective of what the community was telling itself, what the neighbors were telling themselves about who this man was and what happened to those children because there was so little information about what actually happened.

Did Rand ever try to contact you again after the material shown in the film?

Brancaccio: Yeah, he actually contacted us after we filmed and felt that we hadn’t gotten his story right. He was very good at manipulating us or keeping us engaged in conversation with him and that was kind of just another way to keep us going and keep us interested in him, I think.

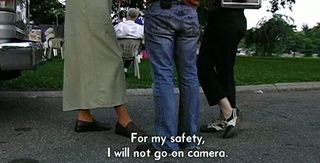

We never get to see exactly what happens inside the prison. Can you tell me a little about that?

Zeman: Well, it was pretty much like the other detective said. We go in there and we’re ready to go interview him, he’s ready to talk to us and they say, ‘Oh, we’re ready for you. Come on out we’ll set the cameras up,’ and he says, ‘No.’

Did you ever get to see him face-to-face?

Zeman: Yes. Every time we would go in there, he would decline to speak to us. We got to see him in the courtroom and we were able to like share looks and things like that, but we had a very interesting and a very weird sense of communication, just the correspondence through the letters and not through talking.

Other than Rand, was there anyone else you would have wanted in the film that wouldn’t do an interview?

Zeman: I wish we were able to speak to the relatives of two nurses who disappeared at Willowbrook, one was named Shin Lee and the other was named Ethel Atwell. They disappeared in very strange circumstances in the woods surrounding Willowbrook and I wish we had been able to include them and their stories because we felt that they were somehow connected to this story.

In the end, Rand is convicted, but like you mention in the movie, there’s no hard evidence linking him to the crime. This just could be a case of a community pinning the crime on the crazy guy in town. After all of this, do you really believe he’s the one who committed the crimes?

Zeman: What’s interesting is that Barb and I had two different ideas about guilt or innocence and what’s interesting is while we were making the film, our versions switched, our opinions switched. I don’t really know if he’s entirely innocent, I don’t know if he’s entirely guilty either. One thing that does come up in the Q & A’s is when people ask, ‘Did the kidnappings stop?’ and the answer is yes.

So what’s next for you? Josh, I know you’re working on the film Ceremony.

Zeman: Yes, executive produced that movie, maybe doing another film with a friend of mine, but concentrating a lot on directing and writing. I’m trying to do a science fiction film and hopefully a narrative version of Cropsey.

And what about you, Barbara? Are you going to stick with filmmaking?

Brancaccio: I’m actually a deputy commissioner for the city government and I think that I’m going to continue doing the work that I do, both community work and local politics and social work and so forth and I’m going to stay with that and then of course, if another opportunity to tell a story that I really believe in comes up, I’d be happy to make another movie.

Staff Writer for CinemaBlend.

Most Popular