Interview: John C. Reilly

We’ve seen John C. Reilly as a NASCAR driver, a porn star, and any number of average Joe husbands, but never before have we quite seen him like this. As rock legend Dewey Cox in Walk Hard, Reilly chops a boy in half, causes a riot, marries a 12-year-old and makes out with a chimpanzee—and that’s just within the first 30 minutes. In his first starring role Reilly goes for broke, taking Dewey Cox from his first band at age 14 to his lifetime achievement concert at age 72; on the way he does every drug, goes to jail twice, fathers dozens of children and encounters every rock legend from Buddy Holly to the Beatles.

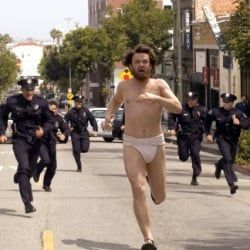

Reilly’s been a prolific dramatic actor for years, but lately has been blowing up in the comedy world. He says he doesn’t have what it takes to deliver a funny line the way Bill Murray or Will Ferrell could, but go to any multiplex this weekend and listen as Reilly gets the audiences rolling in the aisles. He spoke with a group of reporters on the guts it takes to do scenes in your underwear, meeting the real Dewey, and many, many bad jokes and puns on the name “Cox.”

So did you listen to every Dewey Cox record before you started work on this film?

I did. I did exhaustive Dewey Cox research. I met with his family and his estate, went through his archives. Yeah. I got to wear some of his clothes in the movie. That diaper, that sumo diaper, is actually is. It fit perfectly, believe it or not.

Did he see the movie before he died?

He was on the set. He caused a lot of trouble on the set. He’s not the easiest guy to get along with.

Did he give you any pointers?

CINEMABLEND NEWSLETTER

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

He just said, “Tell it like it is, kid,” and then he said, “What’s your name again?” “It’s John Reilly, I’m playing you.” He said, “OK, well you’re not as good looking as me, but good luck to you.”

Did he tell you to walk hard?

Yeah, he said that over and over. We got sick of hearing that by the time he passed away. Like alright dude, we get it. We heard the song, we get it.

How’s the tour going?

The tour’s going really good. We had a few days off—we did the show in Los Angeles last week. We’re playing the Knitting Factory at the finale. It’s a lot of fun. It beats just the basic Q&A, in terms of getting to interact with the fans of a movie. It’s one thing to introduce a screening and say thanks for coming, and then it’s another thing taking the entire audience from a screening and bringing them to the music club and perform all the music from the movie. It’s ridiculous fun. I should not be getting paid for it. Wait—I’m not, that’s right.

When did the idea to do the concerts come up?

That’s something that we immediately started talking about when we were recording the music, because a lot of the guys involved in the music—the songwriters, the musicians, and Mike Andrews the producer […] as soon as those guys get a song that they like on tape, they go, “We’ve got to get out and promote this thing.” And then the studio was kind of into at first, and then the writers’ strike happened. They realized, “Wow, this would be a great way to get, like, word out about the movie, and share the experience of the music with people. Since we can’t have you going out on talk shows…” Then they got really behind it. It’s been really fun, I have to say. It’s a lot of work, it takes a lot of energy to go out there and do that. But to hear the whole club full of people chanting “We want Cox!” before a show is something that everyone should experience, if they can, in their lifetime.

What’s the difference between performing the songs on set and for an audience of fans?

Yeah, it’s kind of strange. Within days of the soundtrack coming out we had people singing along to the songs at the concerts. It’s kind of bizarre how quickly people pick stuff up, or how catchy these songs are.

I know that you were involved with writing some of the music. How much did you do, and where did that come from?

I did a little bit of writing on almost every song. I’m not credited on every song, but we rejiggered the lyrics a little bit to make them funnier, or changed the wording of something to make it sound more like the character was saying it. Then there were many different ways that I collaborated with the songwriters. Sometimes I would just pitch them an idea […] Then another way was the guys would write a song and the lyrics would just be kind of straight and not be very funny, and I would go back through the song and rewrite the lyrics, but keep the music the same. So then I’d be a co-writer—I wrote the original lyrics, they wrote the music.

What is about Judd that fits in with your sensibility, and why is he so easy to work with?

I think the secret to Judd’s success and the reason that actors as well as audiences really like him is that he’s so honest. When he finally got the chance to really tell his stories, he made the bold choice of telling the truth. Just saying, “I don’t care if it’s a taboo subject, I don’t care if it makes me look stupid or it’s embarrassing to me personally, to my personal life, if I admit to thinking a certain way about certain things.” And he just laid it all on the line. From 40-Year Old Virgin to Knocked Up and a lot of the movies that he produced and co-wrote as well, he tells the truth, and he tells it in a really frank way. And he lets the actors improvise in a way that’s just totally truthful because it’s coming off the top of their heads. Today, with the media being so carefully controlled and vetted by lawyers and designed not to offend, it turns out that being honest is a really radical thing to do. And people really responded to it. That’s why I like Judd. He’s a great collaborator too. He’s very similar to Will Ferrell and Adam McKay, in that you’re just standing around pitching gags to each other, coming up with funny ideas for a scene. It’s not like, “Oh, it’s Judd’s idea so we have to do it.” It’s whatever makes everybody laugh. The best joke wins. It doesn’t matter who said it. […] They call it the wide net theory. It doesn’t matter—whatever comes into your head, say it.

Talk about the male nudity in the movie.

Jake claims he saw some biopic about the Rolling Stones where some guy was standing there with like nothing on for like a half hour doing a whole scene or something in the movie. And he just thought that was so funny, how this nudity had just become so gratuitous. And it wasn’t sexualized in any way, it was just there. He decided to add it to the movie. Judd immediately loved the idea too. I don’t think it’s such a big idea. It’s funny that it’s scandalizing people so much. At the end of the day, look, it’s just a human body.

Speaking of baring it all, you spent a lot of time doing some nudity in the film. Was that something that was new for you?

Oh yeah. I’d barely kissed anybody in a movie before. There were lots of moments that were like personal boundary moments for me. But here’s the thing, with comedy—and I learned this from Will Ferrell—you can’t be ashamed. If you’re doing comedy you have to fully commit to the joke. Shame is not part of it. If you act shy or uncomfortable about your body, that makes the audience shy and uncomfortable. And in a comedy you just want them to loosen up and laugh. I really learned that from Will, to just be brave and damn the torpedoes, and if you’ve gotta be in your underwear so be it. If it’s funny, then you should do it. If it works for the gag, then who cares what your body looks like or whether people think you’re sexy looking or not. That’s not the point in a comedy.

It’s interesting how Jake marshaled everybody’s talents toward this one, very consistently funny and consistently styled, amazing film. How did he communicate to everybody—how did he get them all on that same page?

Like all great directors, he really pays close attention to every decision that’s being made. And to be honest, a lot of the feel of this movie was decided during the recording process, in the six months leading up to it. Every time we made a decision about what a song should sound like, and the music it should emulate, or what my character as a songwriter was saying in a given period in his life, we were making decisions about what the movie would be. It’s funny that you remark on the consistency, because at first, when we first started putting the movie together, the consistency was actually hurting us a little bit, I think. We were so concerned with having the movie look like a real biopic, and not stepping out or doing anything that was anachronistic to the time period, or having anything that looked wrong for the time period. We wanted it to be like a virtual biopic experience when you see the movie, with the cinematography and the costumes, the music, everything. We realized when showing the movie to audiences, trying to make the movie the comedy that it needed to be, that those moments when I turned to someone and said, “What the fuck did he just say?”, or whatever it is, pardon my French. Those moments in the movie are the ones that, when we break away from the consistency, is what really gets people energized. The audience, when they’re lulled into the sense that they’re watching a Ray or a Walk the Line and then all of a sudden someone’s in a sumo diaper, cawing like a dinosaur. It was those moments when we deliberately break the consistency of the movie that give it its freshness and surprise and originality.

Even with all of those things that you mentioned, those things that go along the bias between reality and fake, there are two parts where you tip the hand beyond the measure of possibility, and that has to do with people getting cut in half. But you’re totally there with it, and you believe it.

That was the thing, that was the ridiculous exercise of this movie, and why I think my entire career has been leading up to me being able to play this part. Just because I’m speaking Yiddish in a scene doesn’t mean I’m not really pleading for my freedom in jail. Here I am sitting across from one of the icons of comedy, somebody who I have revered my whole life—Harold Ramis—and I’ve got to speak Yiddish to him and beg him to get me out of prison. But the only way I know how to do it is to do it as real as possible. I don’t know how to be like a Bill Murray or a Will Ferrell, these guys who know how to make a line funny just by, I don’t know, some extra-sense perception. I only know character and emotion and real acting; that’s all I know how to do. I would say that to Jake, like, “I hope this is funny, because I’m just going to commit to it as fully as I can.” He’s like, “Don’t worry, don’t worry. The more honest you are and the more you commit to it, the funnier it is. It’s not like we’re winking at all this stuff. You’re actually—you allow us to experience what this guy is going through, because it seems like you’re really going through it.” So, if I have any rules about comedy, that’s it. Decide what the character believes and stick to your guns.

Were you thinking about guys like Johnny Cash and Elvis in your head, and who were some of your favorites?

A lot of the people we reference in the film are my musical influences, from Elvis Presley to Johnny Cash to Roy Orbison, Bob Dylan, Don McLean, Brian Wilson. I’m a fan of every single kind of music that we reference in this movie. Yeah, we were definitely thinking of the musical styles of these people as we were going through the time periods. They were the emblematic people of these different time periods. We weren’t deliberately trying to, you know, poke Johnny Cash in the eye or something. We weren’t trying to make fun of musicians’ actual lives. What we were trying to do was make fun of the way that ordinary, or sometimes extraordinary people are mythologized by movies and by audiences and this whole kind of cycle of mythmaking that happens. I’ll say this: Even though we were going out of our way to evoke the music of these people, I was not trying to do an impression of Johnny Cash or Elvis or Buddy Holly or Bob Dylan. In Dewey’s mind, he’s the fountainhead of all of them. Dewey thinks he was Elvis before Elvis was Elvis. Dewey thinks he was Dylan before Dylan was Dylan. From his point of view, it’s all about him. I’ve been having a lot of fun with it in the concerts. Dewey has said things like, “I have the power of 2 Elvis Presleys, and the poetry of 10,000 Bon Jovis.” He believes he is the ultimate rock star, and the fountainhead of all modern American music.

After this tour, do you think that John Reilly becomes the Cox?

We’ll see. We’ll see how much people love Cox. If they really do, and they want me to keep doing it, I will. But I’m not one of these actors who’s going to force it down peoples’ throats. [Laughter] I’ve made a lot of jokes about the name of this movie, and that’s the first time I’ve made that one.

Do you like doing comedies more than dramas now?

I like working. I wish I could say I made a deliberate choice to comedy, but it’s just what came my way. It’s what the studios wanted to make. Some of my friends were doing it, like Will Ferrell and Adam McKay, and they offered me Talladega Nights. It’s just nice work if you can get it. It’s a joyful day at work, making your friends laugh. I look forward to a lot of different things in my life. I hope it lasts a while, and I hope I keep working. If people want to see me in comedies, that’s fine with me.

Well congratulations on the Golden Globe.

Oh, thanks.

With nominations and things like that, at this point do you just brush it off, or does it still excite you?

Oh, it’s still exciting. You know what that is—it’s sort of like those awards show are a convention at the end of the year. If I was selling plumbing supplies, it’d be like getting salesman of the year. That’s what it feels like to me, that my peers and the people that really know my industry have said, “Hey man, you really stood out of the pack this year, and congratulations.” It’s great. I hope I never win one of these things, because the pressure of what to do once you’re the crowned one—I don’t know what I’d do with that pressure. I think it’s better just to be in the club. It’s almost like the nomination is better than the win.

Are you looking forward to seeing people like Philip Seymour Hoffman and Paul Thomas Anderson on the circuit?

Yeah, exactly. In the same way like I just mentioned, those awards shows are our convention. The Golden Globes in particular. You know, the Academy Awards, it’s almost all film people you see there, and you have to sit in this little seat in an auditorium. If you run into people at parties it’s nice to see them. But the Golden Globes—every actor working is there. Everyone from TV, everyone from cable, everyone from movies. Sitting at these tables you actually get to walk around and mingle. It’s actually kind of fun.

Is there anyone you’re rooting for this year?

I’m very close friends with Paul Thomas Anderson, and I’ve gotten to know Daniel Day-Lewis over the years. I really hope that those guys get some attention, because I think that movie is a real achievement for Paul. It’s such a departure from his other work. I was just staggered by it. I’ve seen it a couple of times, and I really have high hopes for that one.

Were you sorry not to be a part of it?

Uh, yeah. Sure.

It almost seems like it would be strange to see you from the older movies.

Yeah, and that was the thing. Paul and I talked a lot about it. He wrote me a part for the movie, and I said, “Don’t put me in there just because you think you have to, because we’re friends. Put me in there if I’m the right guy to be in there.” And he thought about it, and he was like, “You know what? You’re right. You just talked yourself out of a part.” I was really glad. That movie just seems so seamless. It just seems like he discovered this real place.

How in touch with your Irish roots are you?

I’m pretty in touch with them. I was raised Irish Catholic in Chicago. My mom is Lithuanian. Yeah. They’re trying to get me to go to Dublin with the movie. It will be my first time in Ireland. I’m looking forward to that if it happens. Like most Irish Americans I’m very proud of that part of my heritage.

Staff Writer at CinemaBlend

Most Popular