Spielberg Double Feature: Munich, War Of The Worlds, And The Darkness Of 2005

With Jurassic Park coming back to theaters this week, we're looking back at the years when Steven Spielberg released two films, and how those films reflect on each other. Earlier this week Sean dug into 1993's double feature, Jurassic Park vs. Schindler's List, and Kristy tackled 1989's Always and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Today Katey takes on 2005, when Spielberg released Munich and War of the Worlds.

Less than four years passed between the attack on Pearl Harbor and the end of the global war that the U.S. entered because of it. Just shy of 60 years later the World Trade Center was destroyed, but in 2005 the United States was four years into a secretive, muddled war with no end in sight. Two weeks before Steven Spielberg released War of the Worlds in June of that year, five Marines were killed by a roadside bomb in Western Iraq. In December of that year, as Spielberg's Munich was heading to theaters, President George W. Bush admitted for the first time that the invasion of Iraq was based on bad information.

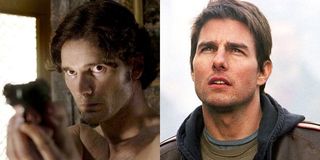

Spielberg's war movies have been exclusively about the two World Wars-- conflicts with clear national boundaries and treaties, and the historical distance to spin tragedy into triumph. But after 9/11, America's most iconic filmmaker could not shake the lingering national wound and the endless war that came from it, releasing two of his darkest and most morally conflicted films. One was a massive summer blockbuster, the other a two-and-a-half-hour Oscar nominee; one was led by the planet's biggest star and the other by a cast of unknowns and character actors; one features alien bad guys, and one doesn't allow for the existence of bad guys at all. But War of the Worlds and Munich both allow Spielberg to step into his familiar role as the American pop culture conscience-- but at a time when straightforward morality no longer mattered.

There are blatant 9/11 references in Munich and War of the Worlds-- the Twin Towers at the center of Munich's closing credits, Tom Cruise coming home covered in gray dust after the first alien attack-- but the nods to the Iraq conflict are knottier and denser with meaning. At the beginning of Munich, when Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir begins planning the assassinations of Palestinians who organized the slaughter of 11 Israeli Olympic athletes, the language is thick with false righteousness. "It's the same as Eichmann-- you didn't want to share this world with us, we don't have to share this world with you," Meir says to her cabinet, explicitly referencing Holocaust mastermind Adolf Eichmann but also George W. Bush's "you're either with us or against us" ultimatums. Sensing discomfort in the room but sticking by her plan, Meir reminds her confidants that "Every civilization finds it necessary to negotiate compromises with its own values."

That's the thesis statement of Munich, which spins out a heavily fictionalized story about the Israelis hired to carry out these assassinations, and revenge comes at the cost of sanity, safety and their lives. Eric Bana's Avner starts the film as a reluctant warrior, but even the most gung-ho-- like Daniel Craig's hulking Steve and Mathieu Kassovitz's bomb-maker Robert-- are shattered by the end of their quest. The decision to individually target the men who planned the Munich attack is far simpler and ostensibly cleaner than, say, invading an entire country as retribution for a single terrorist attack. But nothing is quite so simple. Avner decides to veer off course and kill the woman who killed his friend. The same man (Mathieu Amalric's perfectly slimy Louis) who helps Avner find his targets sells him out to the Palestinians. Decades later, Iraqi insurgents would be murdering U.S. soldiers years after "mission accomplished." Revenge never works the way you planned.

The moral universe of War of the Worlds seems much simpler on the surface, with the invading pods pulverizing humanity so ruthlessly that it's impossible to root for anything other than our survival. But as Badass Digest recently pointed out so well, Ray's development into a good father requires an embrace of selfishness, the kind of "my life is more important than that life" rationalization that drives the assassinations of Munich or the 120,000 Iraqi civilians killed since 2003. The beginning of the film is crammed with 9/11 allusions, from the groups of onlookers gaping in horror at the sky to the flyers for missing people that paper public spaces, but the film immediately heads in a direction very different from the stories we tell about the way we acted after 9/11. People push each other out of the way and wield guns to get what they want; people, Ray included, steal and kill just to get one step ahead of the frantic masses. One of the most blatant 9/11 references is also the most false-- as Ray's family approaches the ferry, a woman announces they no longer need blood donations because they have plenty. Who in this grim, desperate scenario would have donated blood to begin with?

Near the film's end humanity does begin to redeem itself, as fellow captives in the tripod help Ray plant a grenade inside the machinery, and the military organization in Boston helps corral survivors and bring down a tripod at last. The humans here are fighting a "good" war, like the one in Saving Private Ryan or War Horse, and the much-derided happy ending allows us to believe that the humans won a righteous victory. But nearly all of War of the Worlds is about not fighting at all, as Ray and Rachel struggle to hide from the tripods or run away. Tim Robbins's histrionic Harlan, wielding a shotgun and promising to fight back, shouts "This is an occupation! Occupations always fail!'-- a line with unavoidable real-world connotations in 2005. Ray takes the gun from his hands. Even after a historic attack, even when humanity is in shambles and the enemy is a terrifying space creature-- Spielberg says the retaliation isn't worth it. Not, at least, until you really know how to fight back.

CINEMABLEND NEWSLETTER

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

Though flooded with cinematographer Janusz Kaminski's signature milky, heavenly light in many scenes, both Munich and War of the Worlds are at their most beautiful when they are at their darkest. Avner's first assassination, of the old man standing by his elevator in Italy, is lit spectacularly, concluding with the unforgettable shot of blood pooling into the puddle of milk. When Ray steps out of the basement to find the countryside covered in red vines made of human blood, it is surreal and gorgeous like a perverted Wizard of Oz-- and also one of the most sinister images Spielberg has ever concocted. Both films are shot roughly according to their genre, with Munich's zoom lenses and tight, emotional close-ups contrasting with War of the Worlds's massive action set pieces, but an abundance of night scenes and a bleak color palette imbue both films with the gloom reflected in their stories. They look fantastic, but unbelievably different from the poppy zip of Catch Me If You Can, the florid beauty of War Horse, or even the shiny, futuristic bleakness of Minority Report. They are rough and grim in a way that can't be separated from the present-- or the all-too-real past.

There is one shot in War of the Worlds in which Ray looks strikingly like Avner. Having killed Harlan, he crumples on the stairs of the basement in exhaustion and shock. Rachel (Dakota Fanning), having been blindfolded throughout the ordeal, goes to sit next to Ray, offering comfort to a father who has failed to connect with her at all until this point. Ray killed Harlan to protect Rachel, and Avner killed to protect family as well-- though not the wife and daughter who are now safe in Brooklyn. In their meeting at the beginning of the film, Golda Meir pointedly tells him, "Truth to be told, you don't look much like your father. Your mother is who you resemble." Later, his wife says it even plainer-- "Now you think Israel's your mother." It's that step removed, of being asked to consider an entire nation of people your mother, that makes Avner's fight so difficult-- killing others in the name of a flag, not the daughter who will comfort you after. At the end of War of the Worlds Ray reunites his family, and though he's still distant from his ex-wife, he has her gratitude. At the end of Munich, Avner has his final conversation with Geoffrey Rush's Ephraim, a representative of his "mother" who has to reassure Avner she is not trying to kill him. Avner asks Ephraim to break bread with him and his family; Ephraim walks away.

In nearly all films, Spielberg's included, killing in the name of family is the noblest, most necessary choice there is. In Spielberg's previous war films killing and dying in the name of country was just as vital, or at least respected-- but not in Munich. It is not just blockbuster genre standards or Tom Cruise starpower that makes Ray the clearer hero of Spielberg's 2005 films. It's his choice to fight for the only thing that matters-- family-- and to avoid any conflict beyond it. That's not the attitude Spielberg had with Saving Private Ryan, and it's not what he'd express six years later in War Horse, but it was the only one possible in 2005, when death and disaster and quagmire seemed endless in Iraq and in Israel's own ongoing conflict. It's jarring to look back and find the big-hearted, humanist Spielberg there; you want to jolt him forward to 2012 and the passion for American exceptionalism he showed in Lincoln. But pairing War of the Worlds and Munich provides an unforgettable, sobering portrait of America in the middle of the last decade, when heroism seemed so distant that the best choice was to hold close to loved ones and wait for the storm to pass.

Staff Writer at CinemaBlend

Most Popular