In the first scene of Miracle at St. Anna, an elderly black man with a Purple Heart on his shelf watches a boilerplate John Wayne war movie, in which Wayne, the noble sergeant, commands his brave all-white troops not to quit until the war is won. The man, stone-faced on his couch, mutters to himself "We fought that war too."

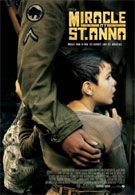

That pretty well sums up Spike Lee's reason for making the movie, which dramatizes the experience of the "Buffalo Soldiers" division of the Army, an all-black regiment essentially used as cannon fodder by white superior officers. Following four soldiers who get separated from the rest of the unit in pastoral, rural Italy, Lee seemingly wants to give black soldiers their own heavy-handed Saving Private Ryan, their own unbendingly patriotic Sands of Iwo Jima, and even their own magical realist Life is Beautiful, all inside one jumbled, inconsistent movie. All at once cynical, hopeful, loving, brutal, truthful and sentimental, Miracle at St. Anna provides so much to be praised that it's possible to overlook the blatant misfires.

For one, there's the electric opening scene, in which our elderly war veteran shoots a man in the face from behind his window at the post office. When a cub reporter (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) discovers a priceless statue head in the man's closet, the story makes international news-- "Marble Head Murderer!" screams the Post headline. Before we find out the identity of the murderer, we head to a flashback, where it is 1944 and the Buffalo Soldiers are trying to push across an Italian river and into German territory.

The following scene, the only full-fledged battle we see, is also the film's most stunning. The German equivalent of Tokyo Rose (Alexandra Maria Lara) broadcasts propaganda to the soldiers, promising soul food and racial equality on the German side. As the Americans push forward the Germans hunker down in wait, while the white American commander abuses the black lieutenants under this command. When the bullets start to fly, the resulting battle sequence is as good as any ever filmed, equal parts harrowing and thrilling, with a peaceful river as its backdrop.

When the dust has settled, we finally meet our four main characters, the only soldiers to make it across the river thanks to a foul-up on the American side. There's Aubrey Stamps (Derek Luke), the ranking officer and the most level-headed of the bunch; Bishop Cummings (Michael Ealy), the sex-crazed hothead; Hector Negron (Laz Alonso), the Puerto Rican radioman without a dog in any fight; and Sam Train (Omar Benson Miller), a slight dunce with a heart that fits his giant stature. Before the four can even fully regroup, Sam finds and befriends an injured eight-year-old Italian boy (Matteo Sciabordi), who in his half-delusions refers to Sam as "The Chocolate Giant."

Trying to make their way back to the American base, the four soldiers find themselves holed up in a small Italian town, where a family led by the beautiful and feisty Renata (Valentina Cervi) takes them in. From there, well, there's a whole lot that happens, from that titular miracle at St. Anna to some adventures with the Partisans, the Italian resistance group. Perspective shifts constantly, from a meeting between two German officers on a nearby hillside to the American command center, from a flashback from the resistance leader The Great Butterfly (Pierfrancesco Favino) to another flashback to basic training in the deep South. Lee is clearly operating with the word "epic" in mind, and makes an effort to extend his revisionist history not only to the forgotten black soldiers, but the much-maligned Italian and German "enemy."

The result is undeniably striking, even when too many of the small pieces don't manage to add up to a whole. The tangle of supporting characters, from the racist Army commander to the Great Butterfly, don't have enough time to take shape, and the central mystery-- who is the old man, and who did he shoot?-- doesn't drive the narrative the way it should. The tone is all over the place, constantly aided by an overbearing score that highlights every moment; sometimes Miracle at St. Anna is a band-of-brothers celebration of war camaraderie, sometimes it's a bitter indictment of the racism that plagued black soldiers, and occasionally it's a light children's fantasy along the lines of Cinema Paradiso.

And yet, the film doesn't drag over its 160 minutes. And everything is lensed so beautifully by Matthew Libatique, from the yellow leaves of the hillside to the blood flowing past a dead soldier's head in a river. Performances down the line are excellent, even with characters that don't fully develop, and many, many individual sequences-- the "miracle" at St. Anna, the final battle scene, even a love scene-- are downright virtuosic. And in the end, war stories are fundamentally gripping, especially when they turn a rarely explored corner and somehow shine new light on a war that's been told over and over so many times in the last 60 years.

Miracle at St. Anna could have been better written and better edited, and someone should have raised a red flag on its weird, supernatural conclusion. But it's fascinating in its messiness, its willingness to follow tangents and rhetoric in order to tell a broader story, about a lot of people trapped in one place at one time near the end of an awful war. St. Anna is probably too strange and unwieldy to become the classic that Lee wants it to be, but it's a worthy stretch for the director, and a noble attempt to revisit forgotten history. It wouldn't be John Wayne's kind of movie, but then again, that's probably the point.

Staff Writer at CinemaBlend

Most Popular