It’s impossible to watch Talladega Nights without thinking of the 2004 movie Anchorman. They’re the same film, and it’s likely because both movies were directed and written by Adam McKay, with scripting help from Will Ferrell. Talladega Nights may have cars instead of news reporting, but it uses the same scattershot approach to comedy, a random collection of semi-improvised sketches tied together by a loose plot in which our comedic hero is laid low by an arch rival and then must overcome his defeat to regain his place at the top of the heap.

The only real difference between the two movies is that in Talladega the plot is even thinner, and oh yeah, Ricky Bobby doesn’t have a comedic punchline like Steve Carell. Carell can’t be replaced but the movie tries by bringing in Gary Cole to steal the movies’ best moments. Cole’s a criminally underrated comedic talent, and he does exactly as asked. He plays Ricky’s absent father, a guy whose only conversation with Ricky prior to adulthood involves the catchphrase: “If you’re not first, you’re last.” He was high at the time, but Ricky takes this one meeting with his father as a pattern to be applied to his entire life.

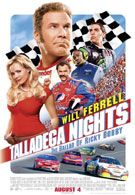

As an adult, Ricky Bobby (Will Ferrell) is stock car racing’s most successful driver. He either wins, or wrecks his car trying. More often than not, he wins. He’s living the perfect world. He’s got a hot wife who loves his earning potential, he has two beautiful sons named Walker and Texas Ranger, and he has his best friend Cal Naughton by his side as a fellow driver. We learn all of this in a half hour montage of Ricky successes, a prelude to the movie’s paper thin plot which kicks in just in time to avoid the film being half over. Story happens when a gay European driver joins the circuit and kicks Ricky’s ass, sending him home to lick his wounds and relearn his need for speed.

Ferrell is back in rare form here, doing the things that made him a box office mega-star in the first place. He hasn’t been this funny since, well, Anchorman; and after a series of missteps like Kicking and Screaming it’s nice to see that he hasn’t lost his touch. John C. Reilly is money as his best friend Cal, he uses that sympathetic thing he does so well to make you feel sorry for him even when he’s screwing Ricky over. Sacha Baron Cohen works as Ricky’s nemesis, though I’m not really sure he’s doing anything that different than he already does with his Borat character. But the improvisational style encouraged on the sets of McKay’s films suits him. Cohen is always at his best when he’s completely off the cuff, which perhaps explains why his overly scripted Ali G movie just doesn’t work. For me the biggest revelation here was Amy Adams, whose been good in movies like Junebug, but never funny. She’s ignored for the first half of the film, but by the end she’s a large part of the picture, and for one scene in particular she absolutely dominates it, pulling off viciously sexy, fiercely passionate and heart crushingly sweet all at once. I think I’m in love.

Talladega Nights works brilliantly in small doses. The film is peppered with unexpected, hilarious asides where Ricky Bobby stops down to discuss why he likes little baby Christmas Jesus better than the traditional adult one, or McKay works in some subtle (or not so subtle) jab at NASCAR’s obsession with product placement. But as a whole, the movie doesn’t quite fit together. In between those funny skits are long pauses for mediocre racing or slight character development. The cast is great, and when they’re in the midst of one of those manic improvisational furies that made Anchorman so funny, The Ballad of Ricky Bobby is a riot. Whenever the movie needs to get to the next chapter though, the momentum stalls out and feels like it’s mired in a pit stop. The cast’s comedic improvisation carries it, but Talladega Nights’ script could have used a tune-up.

Most Popular