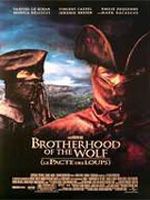

I have seen the future of cinema, and its name is Brotherhood of the Wolf. Forget any of the rules about what you’re “supposed” to do with the camera, with editing, with sound, with the audience’s tastes and desires, and simply accept that the devious French have once again raped, pillaged and looted the accepted Hollywood vocabulary of film and twisted and turned it against itself to ring in the next wave of cinematic Esperanto. Welcome to filmmaking without a net.

Brotherhood Of The Wolf opens with a breathless, desperate rush of fluid camerawork as a rural French woman is brutally mauled by an unseen assailant. Director Christophe Gans is warning us from the beginning that his film is not going to pull any punches, either in terms of story or of style. The camera swoops, prowls and throws itself headlong into the action, staying just a millimeter on this side of losing control. Gans establishes this frenetic yet oddly disciplined style from the beginning and rarely wavers from it for the next two hours and twenty minutes. You almost have to leave the theater every now and then just to catch your breath.

Soon, we meet Gregoire de Fronsac (Samuel le Bihan) and Mani (Mark Dacascos), as they rescue a beautiful young woman and old man from a group of toughs in a torrential Kurosawan rainstorm. As Gregoire stands calmly watching, Mani, a young Iroquios Indian from Canada, makes short Hong-Kong styled work of the assailants without breaking a sweat. We find that a terrifying beast has been killing women and children, and that the King has sent Gregoire, a naturalist, to end its reign and put to rest the rumors that the beast has supernatural origins. Mani is Gregoire’s spiritual brother/protector/constant companion and is the sturdy moral center of this story, although he occupies the edges of the film and speaks no more than perhaps a hundred words. The main female leads are two very different but equally strong characters: The hypnotically mysterious Sylvia (Monica Bellucci), who may or may not be the most dangerous character in the film, and the stunning Madeiline (Emilie Dequenne), who seems fragile and dainty but shows herself to be a strong and determined young woman when the situation calls for it. As the plot twists and turns upon itself, these two weave in and out of Gregoire’s life in surprising ways as the final showdown with the beast inevitably approaches.

Okay, that’s about all I can tell you about the plot, because from here on out there is no conventional plot to speak of. You want romance, the kind of moon-eyed nonsense that a fourteen year old would scoff at? You got it, in spades. White-knuckled “Alien”- styled horror? Check. Powerful martial arts battles to make The Matrix and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragonlook sleepy and outdated? All over the place. Sober Merchant-Ivory styled costume drama? The most heartbreaking and disturbing hunting scene to be found in an entertainment film? Social, political and religious subtexts? Buddy drama? Soft-core sex? Animal activism? Shakespearean tragedy? Henson Creature Shop creatures? Cheesy CGI? Native American mysticism? Winking, broad comedy? Blood and guts? Let’s cut this short and say that just about the only thing missing besides the kitchen sink is a big musical number. Must have been an oversight.

So what’s the big deal? This sounds like a shopping list, not a movie. The big deal is that this is not a Hollywood picture. In a Hollywood picture, would the suits and money grubbers allow a languorous shot of the camera gliding over a woman’s body to be faded into a tracking shot of hilly countryside? That can’t be done in Hollywood – the audience will either be confused or convulsed into fits of derisive laughter. And if the camera never stops moving, and if we throw in seemingly random slow-motion shots and freeze-frames and negative images and push every stylistic element and plot twist right up to the edge of parody, how will your average TV watching illiterate yokel know what to think? How can a high-school dropout deal with a movie that switches from high comedy to the vicious and horrifying murder of a child to a martial arts battle to a queasy incestuous rape scene? The right answer is, of course, let him be confused and annoyed, or let him catch up with the rest of us. Why should someone with a sixth-grade education and the imagination of a salted slug determine what the rest of us should be allowed to see, anyway? If Brotherhood Of The Wolf breaks foreign film box office records in America, Hollywood may be forced to come to terms with this question and make some hard decisions.

So what do we have here? An easy description is that we have a cut-and-paste amalgamation of every dialect from Kurosawa majesty to Spielberg and Cameron shameless emotionalism to John Woo fight choreography to Cronenberg perversity to Hitchcock perfectionism to Bergman symbolism to… well, outrageous audacity and nose-thumbing childish glee at the flaunting of the old rules of order. These influences (and more and more) somehow come together to form an original cinematic language with no limits except those of the filmmaker’s own imagination and daring.

This is not a perfect film. How could it be? There are moments when the envelope-pushing becomes tiresome and laughable, and moments that seem much too serious and solemn for a goofy exploitation/art movie, and the elements that don’t expand the standard Hollywood filmic vocabulary (the choppy, confusing editing in the fight scenes, much of the music, the silly ending) are glaring in contrast to the imagination of the rest. But how can it be less than a modern cinematic treasure? You may love it, you may hate it (and Gans couldn’t be concerned either way), but you will not leave Brotherhood Of The Wolf without a sense that the limits of cinema have been taken out of the hands of accountants and undemanding audiences and put back where they belong – in the hands of the visual poets and artists. For better or worse, this is cinema’s future. Bring it on.

Most Popular