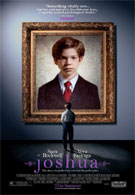

The movie’s title, Joshua, may bring to mind the biblical figure, but the runt-sized star of this modern horror story is far from holy. Jacob Kogan plays the eponymous character, a 9-year-old prodigy from a yuppie, New York City family who is none too pleased when his baby sister, Lily, is born. All hell breaks loose, which is fitting since he could probably be found in the same sandbox as The Omen’s Damien. Or Macaulay Culkin’s character from The Good Son, if you remember that ‘90s kids-gone-wacky tale.

There are very few good thrillers out there, and for a while, Joshua is one of them. Relative newcomer George Ratliff, who directed the film and wrote it with David Gilbert, provides a subdued, eerie vibe that seems to channel Hitchcock--a sideways zoom here, a haunting silence there. It’s incredibly well shot and uses Joshua’s piano playing to build dramatic tension, most notably in a scene where he does a what-the-hell-was-that rendition of "Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star" at a recital. It starts off promisingly and then goes completely haywire, kind of like the movie itself.

Joshua falls into the trap of trying to be too crazy, too gimmicky, too determined to turn the genre on its head. When Joshua yanks out the insides of his stuffed bear to show his dad (Sam Rockwell) how the Egyptians handle their dead, it illustrates his blend of knowledge and flat out creepiness. Those kinds of simple yet poignant moments do the trick. But when the pet dog abruptly dies, along with the animals in the classroom, and a family member takes a tumble off a roof, it borders on the absurd. We can buy that this kid is a dangerous weirdo; it’s harder to buy him as a shining example of superhuman strength and mental fortitude.

The movie works best as an uncomfortable glimpse at a troubled family. Sam Rockwell plays the dad with a sort of playful everyman quality, which is aptly countered by the emotional mood swings that Vera Farmiga brings to the role of mom. Try as they might, they’re not winning any “happiest married couple” or “best parents” trophies.

And when a video tape surfaces that shows her severe postpartum depression after Joshua’s birth, you have to ask: Why exactly would they have another kid? Better yet, why do they let the situation escalate so badly before realizing their kid is the next Ted Bundy? It’s no wonder the boy can play his parents almost as well as he plays the piano--they show the same kind of brainless, bad decision making found in teen horror movies, where the girls dash up the stairs oblivious that the killer is standing there wielding an axe.

Despite the obvious plot issues, in which Ratliff veers away from Hitchcock and starts to echo M. Night Shyamalan butchering Hitchcock, the atmosphere is effective, and the freakiest moments are when Joshua is not on screen and you don’t know what trouble he’s brewing. How sad, then, that the rest of the movie can’t keep up with the slick workings of a kid in elementary school.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News