Cinema Blend Hears A Who: A Visit To Blue Sky Studios

Walking into Blue Sky Studios in White Plains, NY was like putting a Blu-ray in and having the most interactive features imaginable in your hands. Co-Director Steve Martino was on hand to give an in-depth presentation on making the film, the animators were sitting in their cubicles ready to talk about the process and even the sculptors who make the 3D real life versions of the characters out of clay were there to talk about their roll and printing in three dimensions. Ultimately what you come away with is knowledge of how dedicated this team is to their craft, and how much they truly love what they do.

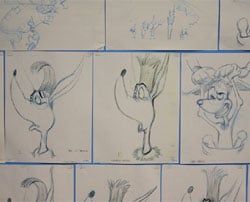

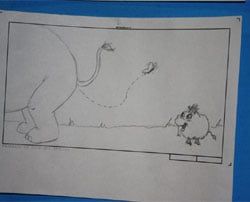

The presentation we were shown was essentially what you can find on the typical extras section of a DVD. Except when something piqued our interest the director was right there to take us through the details. A 3D animated film is a lengthy process and it may seem that some of the classic 2D charm is removed, but in the hands of a talented team this never poses a problem. You see, the animators are actually drawing each scene of the film just as they have always done. What they are given is a new set of tools – developed by the Rigging department – that allows control of the characters. When I heard they use sliders in a computer program to animate with I wondered just how much of an artistic talent one must have to animate in 3D. The answer, it turns out, is quite a bit.

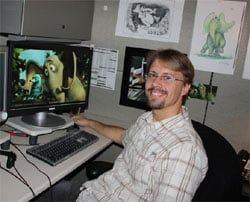

The animators at Blue Sky come from traditional schools of animation, and most still use standard sketching in order to create their characters. Hans Dastrup, who was in charge of The Mayor’s son JoJo, talked about how he’d use his mirror to get the right look and movement for the character. A tricky proposition since, as director Steve Martino pointed out when I sat down one-on-one with him, the art style of Dr. Seuss uses a lot of loopy lines with no real hinged joints. But the personality of each animator makes its way into the characters, and seasoned veterans are able to pick out which scenes a particular animator worked on. The subtle variations in movement, even in the same character, do creep in. This is why it is so important to have character leads in animation to try and keep things as consistent as possible.

Subtle choices like going with the Chuck Jones style of stretch and squash lend a unique quality to Horton Hears a Who’s animation. When I watched the film prior to arriving at the studio I never noticed it blatantly being done, but during his presentation Steve would slow the film down and show us how the head of the Mayor would stretch as he tumbled off screen. Or Horton’s eyes elongating as the bridge fell away. You can often look at an animated film, without any foreknowledge of what you’ll see, and be able to determine the studio behind it. Disney films have a distinct look to them, as do the Loony Tunes cartoons. The determination to go with that Chuck Jones aesthetic was made because it fits the story and look of Horton, but Steve Martino was adamant that they do not want to create a distinct Blue Sky style of animation. The goal is to always go with what fits best with the story. As he pointed out there would be a lot of questions if the characters in Robots had stretched, what with them being robots and all.

When you choose to cast veteran improv performers like Steve Carell and Jim Carrey you’re bound to make some allowances. At the start of the animation process the animators knew they wanted really big and exaggerated facial expressions. But then Jim stepped into the sound booth and Steve Martino had to go back and make everything even bigger. The way it works is the actor is told what the character is about and what the limits are, but then they’re given the freedom to interpret as needed. Sometimes you get a performance that is so spot on that it is worth going back and reanimating to get the nuances just right. Horton himself was deliberately chosen to use Jim’s natural voice as a base, so that when things went crazy with the voices and shenanigans they would juxtapose with the normal state of Horton. Again this goes with the Chuck Jones animation style Blue Sky was aiming for. You can’t reach extremes if there’s no base starting point to launch from.

Any fan of animation knows that without music there is no story. Music lays the foundation for how the animated story is told. Some studios, like Disney, are a bit more obvious with the musicality of their films. What composer John Powell did with Horton is to dictate the pace and syncopation of the story. In particular the final sequence with the Who’s shouting to be heard by Kangaroo (Carol Burnett) and the other forest creatures was dictated by the music. Steve had the music removed from the scene and replaced with a metronome style track so that we could hear how the lines being spoken matched up with a specific beat. This was so important that the actors had to use it in the sound booth when recording their lines. What comes out in the end is almost controlled chaos. There would appear to be a cacophonous din surrounding that final sequence, but listen closer and you’ll discover that John Powell has simply conducted his own original song utilizing the speaking voices of the actors.

I find that where other adaptations of Dr. Seuss’ materials have fallen flat in the past, Horton Hears a Who really does work. And it makes sense, Dr. Seuss himself teamed with Chuck Jones to produce the classic animated TV short based on the novel. Anyone trying to adapt Dr. Seuss would do well to look at what Theodore Geisel was interested in seeing as his characters came to life. Real life people can never ever look like a Who, and that’s why these stories should stay in the realm of animation. Today’s 3D animation can produce that realistic feeling while simultaneously remaining in the realm of fantasy. Horton Hears a Who proves that.

CINEMABLEND NEWSLETTER

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

OK, that’s enough about the film. I mean I walked around a real life animation studio with a ton of cool stuff posted everywhere. The work these people do is time consuming and grueling, and they need to let off steam. Where most office environments encourage workers to get their relaxation elsewhere, Blue Sky plops a large beanbag chair down at a cross section in the aisles of the cubicles. Let’s not forget that these are naturally creative folks, and that means you’ll find a myriad of different things to look at. We walked by cubicles surrounded by curtains, overflowing with figurines and generally looking like they are the perfect place for that person to be able to sit back and feel comfortable in. I particularly enjoyed a few sketches outside of the breakroom that depicted the fictional world Katie talks about in Horton. If you’ve seen the movie you probably wondered what it looks like to poop butterflies, well I got to see it firsthand.

Going into the sculpting department was a bit like walking into a weird college sculpting class where you see the work of previous years. There’s much less whimsy in that tiny room, but the attention to detail these people have is unparalleled. From an obscenely detailed model of Vlad (Will Arnett) to a casting of what were The Mayor’s teeth they had every angle covered. I started geeking out when told that Blue Sky uses a 3D printer to create a lot of the finer details in the sculptures. The printing area is 1 square foot, so some of the models have to be done in pieces. It takes about 8 hours for a piece to print, making it a bit like the dot matrix of 3D printers at the moment.

I’d like to thank the entire staff at Blue Sky for being so gracious and welcoming. They were hard at work on the next project, details of which I have none. But still there was always time for a smile and a brief explanation of what was happening. And how can you not love a place where the breakroom table has comic books embedded under the glass?

Staff Writer at CinemaBlend.

Blue Blood's Tom Selleck Voiced Hopes For The Drama To Continue. Now, CBS' Boss Has Confirmed Where Things Stand

Ghosts: Was [Spoiler] Being Sucked Off Or Were They Dying For Good? I Have A Theory After The Season 3 Finale

Is Grey’s Anatomy Setting Up A Romance Between Simone And Blue? Why I Think Next Week’s Episode Will Bring Them Even Closer Together

Most Popular