60th Locarno Film Festival Diaries - Day 1 In Switzerland

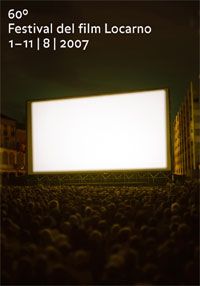

It’s 1am and I’ve just got back from my first big Piazza Grande screening down in the centre of laid back Locarno, a beautiful pastel hued town straggling the Italian-Swiss border, gently hugging the shores of majestic Lake Maggiore. Just hidden away in a corner of Switzerland’s Ticino region, admired for its sunny mediterranean climate and reflecting it’s extravagant neighbour’s colorful ambience, Locarno, is a real find with its grand chalet style houses, ancient buildings and narrow winding roads that climb high into the mountains with their verdant pastures and sub-tropical flora.

With the red hot sun beating down on my back, today, I have managed to move swiftly and with little trouble between various movie theaters and press rooms where I have sat through three movies – all very different in style and tone - as well as attempting to cajole and butter up various members of the press corps into granting me one-to-one interviews. I don’t have any answers as of yet, but I feel I grovelled sufficiently well enough to impress my well-intentioned designs upon them, so here’s hoping!

Anyhow, I could wax lyrical about Locarno’s multitude of delights, the humming atmosphere down town that beckons everyone to immerse themselves wholeheartedly and unashamedly in one of Europe’s oldest and most respected film festivals, not to mention the wonderful and many gelato bars, humungous pizzas freshly made on the premises and wicked little chocolate and cream pastries. So I’ll stop right there and get on with my critique of the good, the bad and the just doesn’t quite do it for me of international cinema.

The highpoint of today’s offering has to be Leopard of Honor winner and special guest of the ‘Retour a Locarno’ retrospective sidebar Hou Hsiao Hsien’s ‘Le Voyage du Ballon Rouge’, (Flight of The Red Balloon) which played out before several hundred people in the elegant environs of Locarno’s main square ‘Piazza Grande’ during late evening. Before the screening director Hsiao-Hsien was invited on stage to receive his award – an impressive leopard statuette before an eager crowd of art-house enthusiasts. The yellow leopard motif it has to be said is emblazoned on almost everything in town from castle exteriors to bistro parasols, however, this did not diminish the importance of this prestigious award that’s synonymous with quality cinema all over Europe and the Taiwanese filmmaker even managed to express his gratitude in a few words of politely spoken English. Now to the movie itself, which confirms Hsiao-Hsien as one of China’s greatest directors of contemporary cinema.

Film: Le Voyage du Ballon Rouge

Director: Hou Hsiao Hsien

Country: France/Taiwan

CINEMABLEND NEWSLETTER

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

Running Time: 113 minutes

Cast: Juliette Binoche, Simon Iteanu, Song Fang, Hippolyte Girardot, Louise Margolin.

The story is about an imaginative young boy called Simon who lives in Paris with his puppeteer/actress mother Suzanne (Juliette Binoche) who is too bogged down with her work and life’s too overwhelming little dramas to notice her son’s obsession with his new imaginary friend – a red balloon, which follows him around the Parisian cityscape – even when he’s on a school trip to an art museum where the class coincidentally observes a painting of a child chasing a red balloon. The red balloon as you may have guessed is a recurrent motif in this film that engages interest on different levels; Simon’s new Taiwanese nanny Song Fang who is also a filmmaker, is taken with the idea of making a film about a red balloon and even refers to the 1956 short film Le Ballon Rouge as her inspiration. Suzanne returns home one day and remarks about the green clad man clutching a red balloon – he is the actor Song employed to help make her film, intentionally dressed in green so that he could be digitally erased from the film giving the effect of a balloon floating by itself. Simon becomes the boy with the red balloon in her film, so the balloon touches everyone’s life; it exists and is not just an object of the mind.

On another level this is a story about the loss of childhood dreams and innocence; Suzanne fondly recalls on more than one occasion happier memories from her youth, initially prompted by Song’s experimental first film ‘Origins’, which she feels a deep spiritual connection with. It’s also about the relationship between parent and child and how although we don’t necessarily stop caring, life itself can sometimes get in the way of us noticing and holding on to that which we value the most. Suzanne’s hectic urban lifestyle keeps the family intact, what with her errant ex-husband working in Toronto and failing to keep up with maintenance payments for their son, then there’s the irresponsible tenant who lives downstairs and has gotten away with missed rent for too long. She’s the lynchpin of a clearly deficient one parent family and although she takes the trouble to hire a caring and involved childminder for Simon, indulges in weekly piano lessons for him even moving his piano to the second floor to avoid distraction from their disagreeable house mate Marc, she barely has time to register him after a busy day at work and is unaware of how far he has progressed with school subjects such as Math.

Hsiao Hsien’s style is economical, crisp and direct, not too intense or over heavy on detail. The puppetry shows are exquisitely rendered and help reinforce the director’s penchant, which he acquired from his homeland, for magical storytelling that draws the viewer in. There are also some wonderful high and low shots of Paris that really capture the city’s urbanite, cosmopolitan feel that’s as fascinating as much as it’s impersonal.

The welcoming of Song into the family unit makes it a kind of ménage à trois, she becomes almost a surrogate mother/father figure for Simon; she is the one he reveals his secrets to, like how he learnt to play pinball and demonstrates both masculine and feminine qualities in activities they do together like making pancakes and introducing him to the world of filmmaking.

It’s also about friendships old and new; as old ties fade into the past new associations burst forth providing hope and restoration. Maybe the overriding message is value your childhood, enjoy it while you can, because adult life is complex and fraught with problems and disappointments. If only we could escape these seemingly relentless dramas sometimes and act like a carefree balloon that floats above it all without any real sense of belonging or accountability.

Film: Ai No Yokano (Rebirth)

Competition: Filmmakers of the International Section

Director: Masahiro Kobayashi

Country: Japan

Running Time: 102 minutes

Cast: Masahiro Kobayashi, Makiko Watanabe, Harumi Nakayama.

In Japan it is strictly forbidden for the parents of a child who has killed another to have any contact with the parents of the deceased. This film, which translates as Rebirth in English is about the unspoken ties between a woman called Noriko whose teenage daughter has killed one of her high school pals and the father, Junichi, who a year after the incident winds up living at the same inn where Noriko just happens to have a job in the kitchen.

Both share the same pent up grief and internalised rage, both are aware of each other’s presence though they avoid looking at each other and any form of physical contact at all costs. While you may ask why on earth do these two clearly distraught human beings who share such an acutely painful past continue living awkwardly in the shadow of each other’s presence, it is ironically this very connection that keeps them together; it’s as if one can’t exist without the other.

Filmmaker Kobayashi who also plays Junichi in the film devotes much painstaking attention to the small, uneventful details of daily life. Without any spoken dialogue except right at the beginning and the end, his camera observes the monotony of Junichi and Noriko’s lives; his daily trek to and from the foundry where he works followed by a hot bath and a meal in the house; the woman making omelettes in the kitchen then returning to a sparse room where she sits hunched on the floor with her head tucked between her knees. Both are unfeeling, remote, closed off and remain such until one day Junich leaves Noriko a gift and gradually they realise that living in solitude is redundant and start emerging from their prolonged vaccum of sadness.

The performances are typically understated; the film in itself is excruciatingly repetitive and low key, complementing the insular and ritualistic lives of the characters. Noriko is the more insecure and reclusive of the two, barely raising her head to acknowledge anyone or anything other than the food she prepares. She is also very obviously living hand to mouth; a packet of cheap sandwiches and a carton drink are all she can afford. Junichi bears the grim fortitude of a man pained by life who like Noriko is initially unwilling and incapable of relating to his environment. The lack of dialogue reinforces the dogmatic approach and the protective bubble surrounding both, the only sound being the domestic and industrial noises of the canteen and the foundry, lending a raw, realistic cinéma vérité feel to the picture. It’s when Noriko and Junichi encounter each other for the first time out of fear, curiousity and the human urge to make contact with a person who understands their unique sense of isolation that they undergo a painful transgression and rediscover a passion, an urgency for life.

Téjut (Milky Way)

Competiton: Filmmakers of the Present

Director: Benedek Fliegauf

Country: Hungary/Germany

Running Time: 82 minutes

Cast: Péter Balázs, Barbara Balogh, Sándor Balogh, László Benedek, Jen? Bodrogi, János Breckl

Téjut is a series of bizarre tableaux without dialogue that feature people in very different situations who communicate or interact through intuition, emotion and body language. Many scenes are based around landscapes both horizontal and vertical. In one a tent standing in an expansive meadow at night is blown away, another features a girl and a boy silhouetted against a cityscape at night, through movement articulating its structure and frenetic rhythms, a man rowing a boat across a serene, reflective lake is watched by an woman who casually abandons a crying infant on the sidewalk. There are other portraits more urban in form ranging from an encounter at a public swimming pool to a stowaway being rescued from a building.

The film, abstract in form, takes us on a sensory journey of image and sound informing our perceptions of reality, the overall effect more closely resembling a video installation with its carefully constructed scenarios that are highly representational in context, transcending words. The surreal music and varying deployment of natural and nocturnal light complement the metaphysical aspect, the chemistry and nature of all things, exploitation of different energies and the symbiosis between man and his environment.

All the while there is an awareness that these ‘humans’ are being observed by some strange, preternatural force from afar as if they are part of some ethological experiment. Although this is not a favourite of mine, Téjut does have a lyrical, dream like quality that can be funny, sad, nonsensical and morbid in turns. It has an artistic cadence of a moving still life.

Most Popular