Adapting Stephen King's The Shining: Revisiting The Controversy Over Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 Film

In October 1974, Stephen King and his wife Tabitha took a trip to Colorado. It was the same month that Salem’s Lot, the former’s second novel and follow-up to Carrie, hit stores, and he was in search of inspiration for his third book. The couple arrived in the mountain town of Estes Park and made plans to stay at The Stanley Hotel – but were surprised to discover that everyone was leaving as they were checking in. The establishment was preparing to shut down for the winter, and the Kings were the only guests remaining.

Having checked into Room 217, Stephen King stayed up after his wife went to bed. He roamed the empty halls, and found himself at the downstairs bar alone ordering drinks from a bartender named Grady. In his mind, wall-mounted spigots inspired images of alive, snake-like fire hoses. The bathroom in his suite had an eerie clawfoot tub. In that first night he conjured what became the barebones for The Shining.

A couple years later, Stanley Kubrick had his own journey to the material – though a far less romantic one. The filmmaker was coming off his first box office failure, 1975’s Barry Lyndon. With aspirations to make his ultimate dream project, Napoleon, he needed to make a movie that could be a financial success. This attitude that put him on the path to adapting Stephen King’s third novel.

What resulted from that collaboration is… complicated. And it all comes down to perspective. Taken completely on its own terms, Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining is a revolutionary and iconic horror film that changed the cinematic genre and has been reverberating in pop culture ever since its release. But is it a great adaptation of the novel? That’s the primary question for this week’s Adapting Stephen King column.

What The Shining Is About

The spooky atmosphere of the empty Stanley Hotel put meat on the bones for the book that became The Shining, but it was because of a preexisting idea lingering in Stephen King’s mind that it properly came together. In his 1981 non-fiction book Danse Macabre, the author describes having once read an article that suggested that haunted houses aren’t so much “haunted” as they are psychic batteries that “[absorb] the emotions that had been spent there” and then spill them out as “a kind of paranormal movie show.”

Through the Stephen King filter, The Overlook Hotel became the ultimate evil psychic battery, and the members of the Torrance family its unsuspecting fuel/victims.

As noted in the memoir On Writing, The Shining was also unknowingly written as a kind of autobiography, with the author not recognizing his own substance abuse issues while writing a story about a struggling writer succumbing to his demons. It’s particularly Jack Torrance’s alcoholism and rage issues that make him a perfect target for the sinister Rocky Mountain lodging, though when we first meet the character he’s actively trying to be a better man.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

Jack brings his wife Wendy and son Danny to the Overlook because of desperation. In addition to losing his teaching job due to an altercation with a student, his relationship with his family is fraught due to an incident that saw Danny injured when Jack was inebriated and yanked his arm too roughly. Agreeing to be the caretaker for the hotel during the winter season is meant to be his opportunity for redemption – as well as the chance to write a book that could additionally aid in turning things around.

Jack’s flaws and insecurities (as well as a subtle touch of the shine himself) make him a puppet for the Overlook Hotel, as a history of criminal behavior and shady dealings on the property have left it teeming with a menacing energy that only grows hungrier. What the Overlook doesn’t expect is young Danny.

Though he is only five years old, the child has discovered that he has a special psychic gift. He has premonitions and telepathic abilities, and can see what lies under the crust of the world. These powers are dubbed “The Shining” by Dick Hallorann, the head chef at the Overlook who also possesses similar talents – though Danny is told that he can dismiss his visions with a powerful enough will. What Dick doesn’t expect is the hotel’s hunger for Danny’s incredible shine kicking the psychic battery into overdrive, leaving the Torrance family susceptible to a cavalcade of deadly nightmares.

How Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining Differs From Stephen King’s Book

In adapting The Shining, Stanley Kubrick decided to make a movie that he was interested in making… and Stephen King hasn’t exactly been shy about expressing his disapproval of the result. While the 1980 film may be widely regarded as a triumph of psychological horror, anyone who has read the source material can instantly recognize how it is a serious deviation from the hit book on which it’s based.

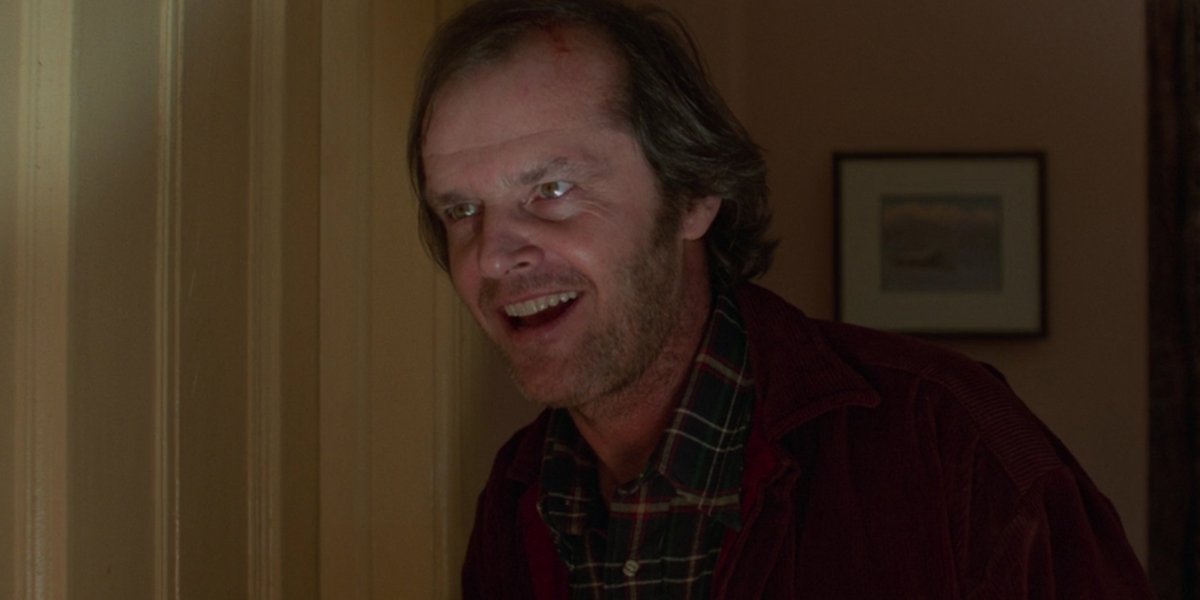

First and foremost in this discussion is the characterization of Jack Torrance. The Shining was written as a decent into madness story, with the Overlook serving as eager catalyst, but that descent is far less pronounced in the film than it is in the book. Stephen King has remarked that the hotel caretaker doesn’t so much have an arc as a “flat line,” which is a consequence of Jack Nicholson giving off sinister vibes from jump street in the movie (he doesn’t exactly come across as a warm and friendly guy during his initial job interview).

As emphasized above, Stephen King originally wrote Jack Torrance as a troubled man trying to improve while simultaneously battling his demons – and that’s a task that the Overlook Hotel forbids him from accomplishing. There is one scene in the film where Jack demonstrates love for his son, sitting with Danny on the bed and promising never to hurt him, but Nicholson’s performance is less about showing a change in the character so much as demonstrating his vulnerability.

That single issue is representational of another major change between The Shining as a book and as a film, which is a matter of tone. While the story may be set during a winter in the Rocky Mountains, it, like many of Stephen King’s greatest works, operates with a special kind of warmth that makes the material inviting before it makes a turn for the terrifying. It’s like a slowly overheating boiler – making things comfortable at first, but leading to an explosive, fiery end (in this case that’s not so much a metaphor so much as it is a literal description of the novel’s conclusion).

Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining is the antithesis of that. It’s a movie that progressively gets colder and colder until Jack Torrance is struck dead from hypothermia at the end and growing icicles off his nose (while the hotel itself remains more or less perfectly intact).

There are numerous more incidental changes as well. The hedge maze, for starters, is a detail that was invented for the film, as Stephen King’s book features horrifying topiary animals that quietly come to life. Additionally, while the movie version of Jack Torrance is established as a writer, it doesn’t get into his work as much as the source material – which finds the character unearthing the dark history of the Overlook (and thus providing context for its abundance of ghosts). King’s novel also notably keeps the caretaker’s crimes limited to simply attempted murder, as he doesn’t actually kill Dick Hallorann; he simply gives him a good whack in the head with a roque mallet (oh, and Jack has a roque mallet in the book instead of an axe).

Is It Worthy Of The King?

In any discussion of how a movie adapts a book, one word that is frequently thrown around is “faithful.” It’s inherently known by any bibliophile/cinephile that material is going to be changed as it makes its way from one medium to another, so expectations aren’t so much based on hopes that a filmmaker will create a facsimile of a novel so much as they are based on hopes that the spirit of the text will be captured by the new interpretation.

In these terms, The Shining is a complicated movie to talk about, as while it is an utterly brilliant film that will forever reign as one of the greatest accomplishments in cinema, it also happens to be a subpar adaptation of Stephen King’s novel.

I highlight King’s expressed criticisms of the novel above because the points he makes are entirely valid when drawing a line between his work and Stanley Kubrick’s. As far as recognizing author’s intent goes, the director and the writer were definitely not on the same page in the making of The Shining – and as a result watching the movie and reading the book are independent experiences. Those who have only ever done the former will gain a completely different understanding of Jack Torrance, all while still being horrified by what he becomes.

As I said at the beginning, however, it’s all a matter of perspective. Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining is not a faithful adaptation of Stephen King’s book, but it is cinema at its most complex, gripping, and stunning levels – not to mention one of the most influential films of all time (it might actually be possible to reconstruct the entire thing using only references, homages, and spoofs in various movies and television shows – from The Simpsons to Hannibal). The cinematography is genius and revolutionary; every inch of the production design is iconic; the editing is hypnotizing; the score is transcendent; and the performances are terrifying. (One criticism of King’s that I disagree with is his assessment of Shelley Duvall’s Wendy Torrance as “just there to scream and be stupid,” as while the turn is certainly hyper-emotional, it also generates a kind of sympathetic fear where her terror becomes our own.)

In the decades since the release of The Shining, the pop culture legacy has shifted a few times in interesting ways – first with Stephen King writing his own miniseries version in the late 1990s, and then with the publication and adaptation of Doctor Sleep in the last decade. But those are projects to be further discussed in future installments of this column…

How To Watch Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining

Over the years Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining has bounced around from streaming service to streaming service, but right now it’s available on HBO Max. Even if you’re not a subscriber, though, it’s not a challenge to find a way to watch the film. In advance of the release of Doctor Sleep in 2019, Warner Bros. released a beautiful 4K edition of the movie and that is available in addition to the widely printed Blu-ray. It’s also available for digital rental and/or purchase on Amazon Prime, Google Play, Vudu, and iTunes.

In the next installment of Adapting Stephen King we’ll have something a bit different for you, as George Romero’s Creepshow will be under the microscope, and I’ll be examining its treatment of the author’s pair of shorts that served as source material: “Weeds” and “The Crate.” Beyond that, stay tuned for all varieties of news, updates, and trivia about old and new King adaptations here on CinemaBlend!

Eric Eisenberg is the Assistant Managing Editor at CinemaBlend. After graduating Boston University and earning a bachelor’s degree in journalism, he took a part-time job as a staff writer for CinemaBlend, and after six months was offered the opportunity to move to Los Angeles and take on a newly created West Coast Editor position. Over a decade later, he's continuing to advance his interests and expertise. In addition to conducting filmmaker interviews and contributing to the news and feature content of the site, Eric also oversees the Movie Reviews section, writes the the weekend box office report (published Sundays), and is the site's resident Stephen King expert. He has two King-related columns.