Adapting Stephen King's Christine: Is John Carpenter's 1983 Classic Still Revving Its Engine?

Adapting Stephen King is taking John Carpenter's Christine out for a spin and seeing how it holds up.

By 1983, Stephen King was a proven Hollywood commodity. In addition to being a popular and best-selling author, it had been spectacularly demonstrated through five feature films and one TV movie how well-suited his works were for adaptation. As a result, the industry began developing King’s books for live-action even before they were published – which is the short story behind how John Carpenter’s Christine arrived in theaters just eight months after the novel it’s based on first hit shelves and while softcover editions still reigned at the top of the New York Times fiction rankings.

Carpenter originally had his eyes on a different adaptation, collaborating with screenwriter Bill Phillips to try and make a feature film version of the 1980 novel Firestarter, but when the vision for that project fell through (more on that in a couple weeks) it didn’t take long for the director to take a swing at a different Stephen King book. He had been given a manuscript for Christine and began talking about it with Phillips, and while the scenarist initially laughed at the idea of a story centered around a haunted car, he didn’t end up needing to finish the book before calling the Halloween filmmaker and confirming his interest in making the movie.

Christine has a powerful legacy, what with it being a collaboration between two of pop culture’s great Masters Of Horror… but one could make the argument that makes it particularly open for scrutiny and reexamination. How does it compare to the novel, and how has it held up over time? Those are the questions revving the engine of this week’s Adapting Stephen King.

What Christine Is About

When the initial idea for Christine started bouncing around inside Stephen King’s head, a rumination on an old red Cadillac he owned, it was a comedic short story. As told by the author to Douglas A. Winter for “Stephen King: The Art Of Darkness,” the mental first draft followed a kid who gets a car with an odometer that runs backwards, and while initially that has the effect of making it more beautiful and run better over time, it ultimately falls “into component parts” when it hits zero.

As things evolved, that kid became Arnold Cunningham (a name inspired by the restaurant and protagonist from Happy Days); that car became Christine (named after George A. Romero’s wife at the time); and the plot took a turn for the sinister.

Christine is the quintessential coming of age horror story, its vehicle – both literally and figuratively – being the great symbol of maturity in American culture. By the time you’re learning how to drive, you’re making the decisions about where your life is going to take you and the kind of person that you’re going to become. As choices are made, formative relationships are bonded, and priorities are ordered, it can be a time of great discovery and painful mistakes. For Arnie, Christine is both.

The book also being in part a Stephen King-style romance, the pizza-faced, nebbish Arnie falls in love with the titular 1958 Plymouth Fury at first sight while driving home from school with his jock best friend, Dennis Guidler. The car is in garbage condition, but it technically runs, and the teen decides he must have it. It immediately causes a fissure in his relationship with his parents, two college professors who refuse to allow the heap of junk to be parked at their house – but that’s just where things start.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

In truth, Christine is not too dissimilar to the Overlook Hotel in The Shining, as it operates as a kind of psychic battery that generates a dark and corrupting energy. It enhances Arnie’s confidence, and even clears up his skin and magically fixes his eyesight, but it also feeds on his soul, and proves to have an agency of its own – expressing envy toward anyone who steals affection away from her (such as Arnie’s first ever girlfriend, Leigh Cabot) and murderous rage toward anyone who might try to hurt her.

How John Carpenter's Christine Differs From Stephen King's Book

Christine is most certainly a mean machine, and very much the star of the show in Stephen King’s novel, but a key aspect of the source material that the movie wholly ignores is that she is a kind of co-antagonist. To continue the psychic battery metaphor, her energy source for decades in the book is her first owner and world class sonofabitch, Roland D. LeBay, and his spirit is not only attached to the vehicle, but a massive part of Arnie’s corruption. The nerdy teen doesn’t just become obsessive, aggressive, and nihilistic, but starts actually transforming into LeBay – using his vocabulary, such as calling everybody a “shitter,” and even seeing his signature devolve into one that looks similar to the crotchety old man’s.

Keith Gordon’s Arnie does still call people “shitter” in John Carpenter’s movie, and there is a deleted scene where Dennis (John Stockwell) and Leigh (Alexandra Paul) notice that their friend’s handwriting has changed, but beyond that Roland LeBay is made out to be the same kind of victim that Arnie is. The film almost circumvents him entirely, as he is long deceased at the start of the story, and it’s his brother, George (Roberts Blossom), who sells Christine. It’s essentially a narrative shortcut, as George is established as a presence much earlier on, and is already around when Dennis begins looking into the car’s deadly history (which is where the sibling factors into the Stephen King book).

The decision by John Carpenter and Bill Phillips to axe Roland LeBay left them with the capacity to shine an even brighter light on the titular vehicle, and the wholly invented opening sequence is an extension of this. The novel sees Christine come off the line in its custom shade of red without issue, while Carpenter decided to crib an idea he attributes to Alfred Hitchcock – the original concept having been a montage of a car being built that ends with a body falling out of the trunk.

With greater narrative real estate, Stephen King’s Christine also features a number of notable plot lines that needed to be either deleted or compressed when being adapted. Dennis and Leigh, for example, don’t spark the same kind of romantic relationship that’s in the source material (some scenes were filmed, but they didn’t make the final cut). There is also a point in the book where Arnie’s father, Michael, makes an attempt to reach out to his increasingly rebellious son by renting him a space for his car at an airport lot, and it’s actually there that bully Buddy Repperton and his crew make their assault on the Plymouth Fury. Moving that action to Darnell’s Garage for the film removed the need for an extra location for the production.

Speaking of Darnell (Robert Prosky), there is also a plotline from the book that paints him as a far shadier operator, quietly smuggling drugs and using Arnie as a willing mule.

Additionally of note is that nearly every death in John Carpenter’s Christine happens differently in the book – and Carpenter actually spares a number of lives. As far as the high school hoodlums go, Moochie (Malcolm Danare) doesn’t get crushed in a narrow ally in Stephen King’s version, but instead is smashed in the street and run over multiple times. Repperton (William Ostrander), Richie Trelawney (Steven Tash), and a third friend, Bobby Stanton, meanwhile, get taken down by the villainous automobile in a deadly car crash while racing through a snowy state park instead of in the fiery incident at the gas station.

The most disappointing death from the book not to see in the movie is definitely Darnell’s. John Carpenter goes the low-budget approach in the adaptation, Christine ratcheting up her driver’s seat so that she crushes him against the steering wheel while he sits inside her, but Stephen King’s book has a bit more flash: the evil car decides to pay a visit to Darnell at home, by which I mean she literally drives into his house and tears both it and him up.

Simply being an asshole instead of a straight up drug smuggler, Darnell is shown some mercy in the film – but getting off even lighter are Detective Rudolph Junkins (Harry Dean Stanton), and Arnie’s parents (Christina Belford, Robert Darnell) – all of whom die in the book but survive the movie. Admittedly the former meets his maker relatively quietly in the source material, run off the road by Christine because she doesn’t like the progress that he is making in his investigation.

As for Arnie’s parents, their endings are tied into key changes made to Christine’s ending. As written by Stephen King, the finale doesn’t actually include Arnie, as the event is timed to when the young autophile is out of town visiting colleges (it’s implied that when Christine is “destroyed,” Roland LeBay’s spirit leaves it to try and complete his possession of Arnie, but when that happens Arnie and his mom are killed in a car “accident”). As for dad, Christine lures him into her cabin shortly before her showdown with Dennis and Leigh and kills him with carbon monoxide (John Carpenter has it so that Arnie flies out of the windshield during the fight, ultimately killing him, but in the book it is Michael’s body).

Lastly, while both versions end with a question mark regarding the fate of Christine, the book wraps things up differently. In a flash forward, Dennis reads an article that says the last of Buddy Repperton’s gang (one not featured at all in the film) was killed in a “bizarre murder by car” – leading him to question if the Plymouth Fury’s rampage really is over even after the big showdown.

Is It Worthy Of The King?

Taking Roland LeBay out of the story has massive repercussions for John Carpenter’s Christine. There is a kind of tongue-in-cheek tone that is instilled when you take the step from the car being possessed by a miserable misanthrope versus being simply evil (which is not to say that Stephen King’s novel doesn’t have its own dark sense of humor), and the context for Arnie’s corruption is altered. Without LeBay’s misery and poisonous attitude infecting the teenager like a virus through the red leather seats, the coming of age metaphor is softened and doesn’t click the same way it does in the book, not to mention that it removes a tool from the adaptation’s horror toolbox.

Along with the other changes, the movie version is its own experience compared to the novel – but as an interpretation of the material it is a winning one. It features a significant number of alterations, but it gets at the core of what the author’s story is about, and it remains a stunning example of pure movie magic that makes its timelessness on par with rock ‘n roll.

Featuring legendary character actor Harry Dean Stanton as the biggest name in the cast, and what amounts to very little action, the movie is intimate and really all about the characters, highlighting what is always the best aspect of Stephen King’s writing. Arnie, Dennis, and Leigh are all traditional archetypes – the nerd, the jock, and the beautiful new girl in school – but the story serves to subvert their traditional roles to the point that they become unrecognizable by the end, and while doing so makes them out to be compelling and unexpected heroes and villains.

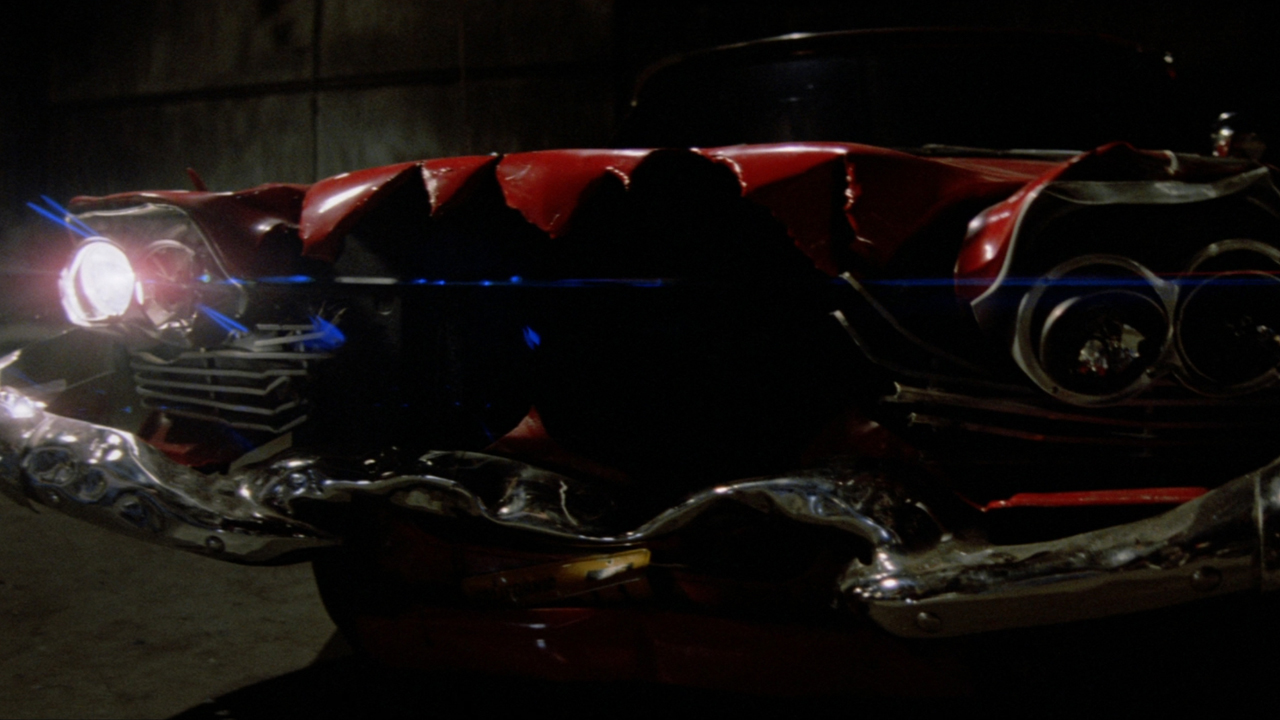

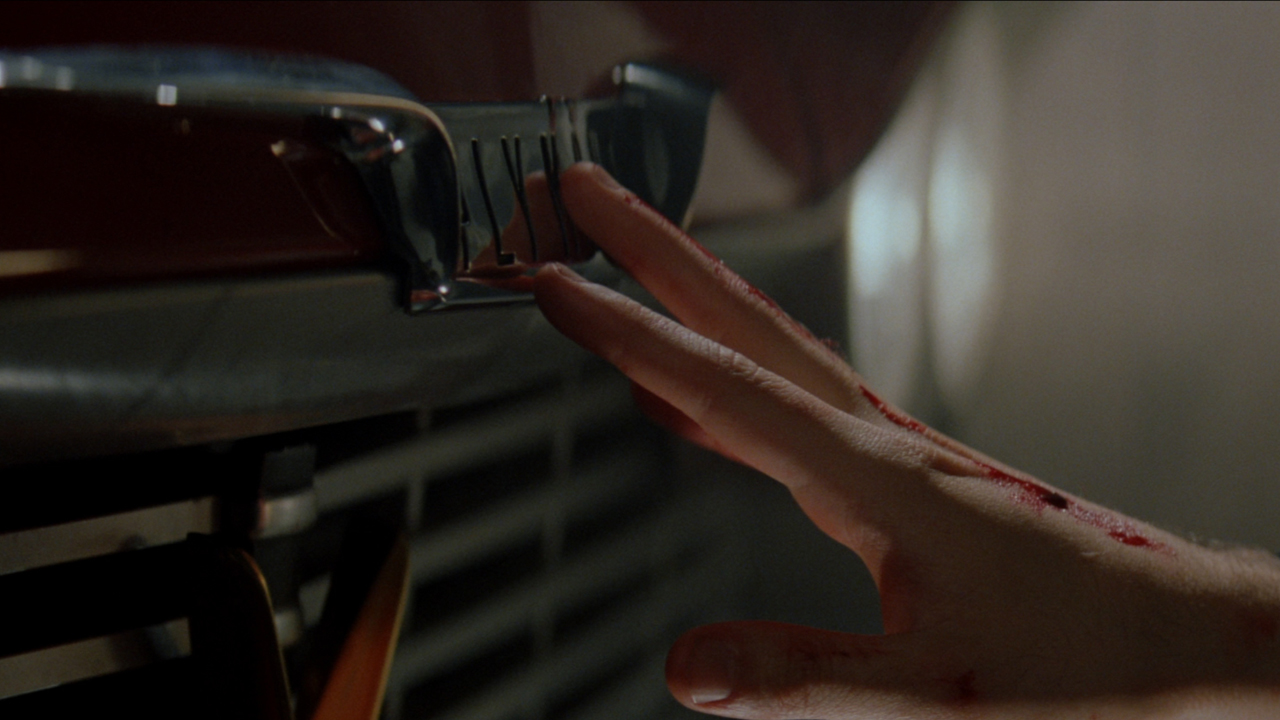

Of course, a significant reason why Christine’s production was scaled back was because of the cost commitment to bringing to life the titular 1958 Plymouth Fury – but that’s just picture perfect representation of John Carpenter knowing where to put priorities. In addition to the car having an arc as strong as any of the other characters’, it’s stunning just how scary she can be. In any other circumstance it would be silly to call a fire red sports car brutal, possessive, and intimidating, but the movie flawlessly grafts those emotions on to Christine, and makes her far more than a machine.

Obviously actions and relationships speak loudly, but it’s also the technical brilliance employed bringing the villainous vehicle to life. Christine rebuilding herself is simply the result of the crew crushing individual parts with hydraulics while filming in reverse with the camera upside-down, but in the moment watching it just looks like sorcery, and it’s spectacular. It still has some freedom to have an air of silly (said rebuilding scene is set up as a kind of sexy strip tease, beginning with Arnie’s “Okay... show me”), but the temperature of your blood also drops as you watch the sedan run down Buddy Repperton on an empty road while engulfed in flames and all you can register is her ruthlessness and indestructibility.

Needless to say, the developing remake of Christine has a tremendously high bar to clear.

How To Watch John Carpenter's Christine

Giving John Carpenter’s Christine the love and care it deserves, Sony celebrated the 35th anniversary of the movie’s theatrical arrival with the release of a 4K edition in 2018 – a set that not only sports multiple featurettes and deleted scenes, but also a commentary track with John Carpenter and Keith Gordon (you can also still find it on Blu-ray and DVD). If you’re looking for a more instant viewing experience, the film is available to rent and purchase digitally from all major outlets, and is currently streaming on Starz.

Coming up next week, Adapting Stephen King will examine a movie that kick-started one of the author’s strangest cinematic legacies: Fritz Kiersch’s Children Of The Corn. Look for it live on CinemaBlend next Wednesday, and click on the banners below to read past installments of this column!

Eric Eisenberg is the Assistant Managing Editor at CinemaBlend. After graduating Boston University and earning a bachelor’s degree in journalism, he took a part-time job as a staff writer for CinemaBlend, and after six months was offered the opportunity to move to Los Angeles and take on a newly created West Coast Editor position. Over a decade later, he's continuing to advance his interests and expertise. In addition to conducting filmmaker interviews and contributing to the news and feature content of the site, Eric also oversees the Movie Reviews section, writes the the weekend box office report (published Sundays), and is the site's resident Stephen King expert. He has two King-related columns.