Arguably the greatest American director since Howard Hawks, Robert Altman is more than just an auteur. He’s a cinematic icon. With a diverse list of films as brilliant and broad as M*A*S*H*, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, Nashville, The Player, Short Cuts, Kansas City, and Gosford Park, Altman has revolutionized American cinema, focusing on the realities of social setting, while also experimenting with avant-garde techniques, like overlapping dialogue, underheard conversations, and unresolved actions. Throughout his prolific career, Altman has explored a wide range of topics, including comic fantasy in Brewster McCloud, high fashion in Prêt a Porter, the venality of Hollywood in The Player, and the myth of star appeal in Buffalo Bill and the Indians. Yet none of his work has been as personal or as beautifully photographed as The Company, his latest film centered on the artful world of classical ballet.

Written and co-produced by Neve Campbell (Scream) and Barbara Turner (Pollock), The Company gives viewers an intimate glimpse into the private lives of the Joffrey Ballet’s talented troupe of dancers. Many of the film’s actual characters, including Deborah Dawn, Trinity Hamilton, and Suzanne L. Prisco are real-life ballerinas, with revered choreographers Lar Lubovitch and Robert Desrosiers rounding out its exclusive cast.

Campbell, a former student of the prestigious National Ballet of Canada, plays Loretta ‘Ry’ Ryan, an up-and-coming ballerina who goes from understudy to star, when swanlike Maia Wilkins, a fellow company member who steals her boyfriend, John (dancer John Gluckman), is replaced after Lubovitch discovers that she’s been hiding muscle spasms in her neck. Performing a new pas de deux set to Marvin Laird’s melancholic My Funny Valentine, Ry and her partner, Domingo Rubio, virtually set the stage on fire as they deliver a flawless performance during a thunderstorm in Chicago’s Grant Park. Watching amid a sea of umbrella-covered onlookers, Alberto Antonelli (Malcolm McDowell, A Clockwork Orange), Artistic Director of the Joffrey Ballet, sits transfixed as Ry pauses between steps, reading the audience, then feeling the fluidity of her body’s movement.

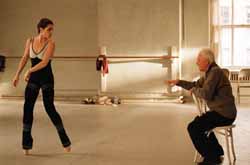

Seeing her innate talent and realizing that he might have underestimated her skill as a principal dancer, Antonelli decides to take Ry under his wing, casting her as the lead in an original ballet entitled “Blue Snake” by French-Canadian choreographer, Robert Desrosiers. But just as Ry’s professional life begins to bloom, so does her personal life. Juggling practice, a part-time job as a cocktail waitress, and a new love affair with an aspiring chef named Josh (James Franco, City by the Sea); Ry struggles to find the proper balance between happiness and career.

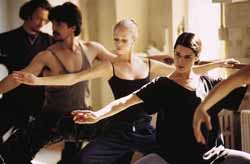

Delving deeply into the elite world of classical ballet, The Company examines the ups and downs of a ballet dancer’s life with unflinching aplomb. Screenwriter Barbara Turner, who spent nearly two years interviewing members of the Joffrey Ballet, gets everything right. From the injuries sustained by the dancers to the competitiveness of the dancers to the average career span of the dancers, Turner’s detailed portrait of what it’s like to be a dancer for one of the most influential ballet companies in the world is not only accurate. It’s downright intense. For example, when a promising dancer named Noel (real-life ballet veteran, Emily Patterson) snaps her Achilles tendon while demonstrating an intricate combination from Arthur Saint-Léon’s “La Vivandi è Re Pas de Six.” Everyone knows that it’s the end of her career, but no one says a word. Perhaps that sounds a bit insensitive to an outsider, but to a professional ballet dancer, it’s a harsh remainder of how ballet tests the body as much as it tests the soul.

Pouring herself into the demanding role of prima ballerina, Ry Ryan, Neve Campbell, who did all of her own dancing and trained with Chicago’s Joffrey Ballet for nearly two months prior to production, inhabits the role like a true artist. Delivering an understated, yet eloquent performance, rich in confidence, grace, and nuance, Campbell conquers stage and screen with a calm sense of focus. Using her body as an emotional tool, the 30-year-old Canadian puts her formal ballet training to good use, building up quiet moments with little more than the extension of her limbs. In fact, in an early scene where Ry enters the studio late after describing her messy breakup with John to friend and fellow dancer, Michael Smith, she walks over to the barre, takes a deep breath, and begins practicing her pliés, as though she were liberating herself from the heart-wrenching woes of love.

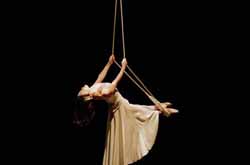

Shot with a digital camera using close-ups of the dancers’ hands and feet, as well as a series of wide-angle shots showcasing their entire bodies, The Company has such an intimate look that it feels more like a stylish documentary than an independent feature. Celebrating the artistic process of ballet, Altman downplays the drama, letting the camera tell most of the story from the outside looking in. Although Altman spends a great deal of time capturing the magnificent splendor of the Joffrey Ballet’s diverse repertory, including Gerald Arpino’s “Trinity,” and Moses Pendleton’s “White Widow,” he nonetheless finds time to poke fun at the metaphoric profundity of The Company, skewering everything from artistic freedom to aesthetic beauty to safe sex like the master of social satire. Many Altman fans will likely find such irreverent humor ironic, considering Altman’s work here. But in the case of The Company, that’s part of the film’s secret success. After all, what’s more entertaining than a movie in which art imitates life?

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News