Having incidentally rewatched Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report within the last month, I can write with refreshed enthusiasm that it’s a tremendous science-fiction vision and a title that stands among the best in the director’s storied filmography. An adaptation of a work by one of history’s greatest genre visionaries, it is smart, thrilling and dramatic in its exploration of its premise, which sees an evolution in the American legal system begin thanks to visions from a trio of mutants with the ability to see the future.

Release Date: January 23, 2026

Directed By: Timur Bekmambetov

Written By: Marco van Belle

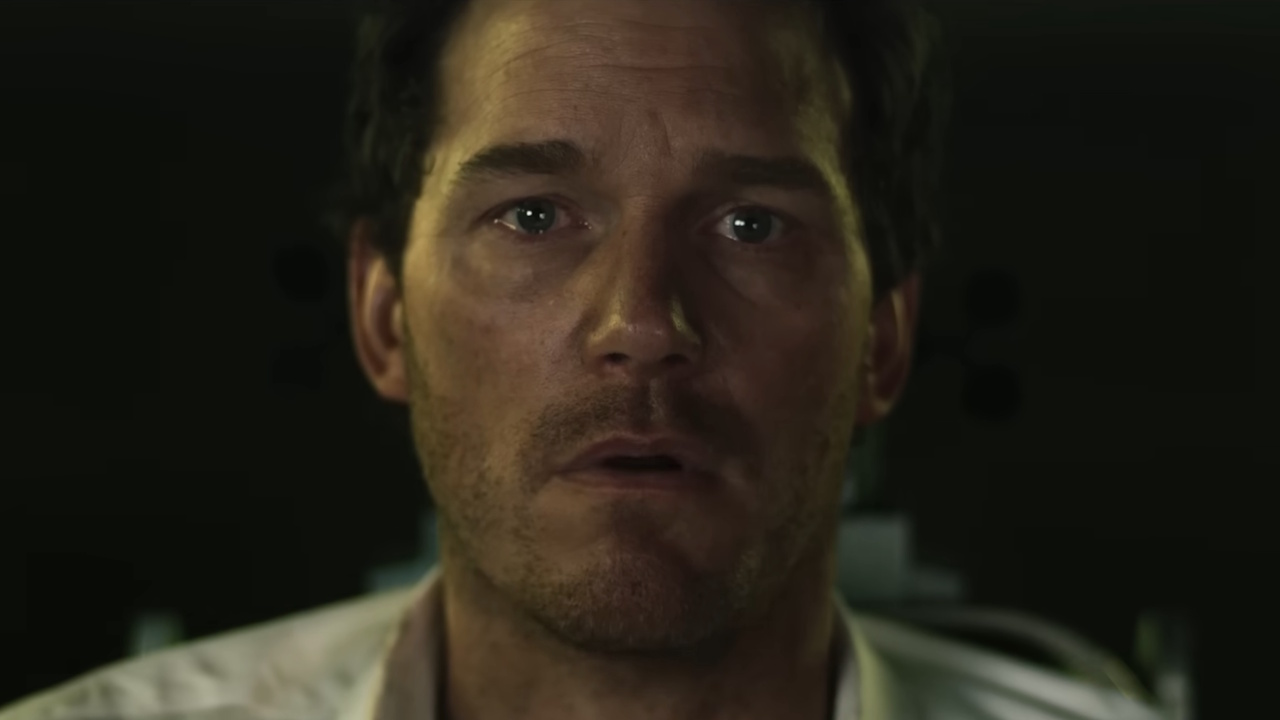

Starring: Chris Pratt, Rebecca Ferguson, Annabelle Wallis, Kylie Rogers, Kali Reis and Chris Sullivan

Rating: PG-13 for violence, bloody images, some strong language, drug content and teen smoking

Runtime: 100 minutes

In the 2002 film, the plot makes sense: the discovery of the so-called precogs changes how humanity comprehends fate, and society attempts to evolve with the development of a precrime police division that stops and arrests murderers before they kill. It’s assumed to be a flawless program… until it’s proven to be both flawed and manipulable, imperiling the life of the story’s principal character.

I make a point of describing this 23-year-old blockbuster because it’s so clearly what director Timur Bekmambetov’s Mercy wants to be. Based on an original screenplay by Marco van Belle, the new film attempts to draw a straight line between the precogs and modern artificial intelligence by imagining a world with a new legal procedure that has the ballyhooed technology at its core, and it centers on a protagonist who is a proponent of the system up until he becomes a victim of it. The problem? The idea doesn’t make a lick of goddamn sense, and because it’s everything that the movie hinges on, it renders the entire cinematic experience a baffling disaster.

The film tries to comment on the dangers of A.I. while unfolding in real time and executing a new take on screenlife storytelling – which is an admirable effort from a creative standpoint – but its foundation is a train wreck, and it makes it impossible for the movie to actually be something interesting, insightful or even fun. It gets some points for being flashy and bold, but it’s also most certainly suited for its January release date and seems destined to become an early 2026 punchline.

Chris Pratt stars as Chris Raven (yup, that’s his actual name), a Los Angeles police officer who wakes up to discover that he has been locked into a chair and is sitting before a digital adjudicator named Judge Maddox (Rebecca Ferguson). He has been selected as the nineteenth individual to stand accused in the Mercy Court – which is particularly significant given that he is famous for arresting the first person who went before the A.I. bench a couple years prior.

Deemed guilty until proven innocent within the new system, Chris is told that there is a calculated 97.5 percent chance that he stabbed and killed his wife (Annabelle Wallis) during a domestic dispute earlier in the day, and the onus is on him to reduce that surety level to at least 92 percent within 90 minutes – at which time he will be executed for the crime. To help him in his defense, the protagonist is given access to every phone, computer and camera in the city to hunt for any new information or suspects that could ultimately exonerate him.

Simply put, this movie makes no sense.

Mercy fancies itself as a kind of cautionary tale given the extreme investment that our world has been put into artificial intelligence (the movie is boldly set in the near future of 2029), but any point it tries to make about the potential danger of trusting A.I. in the legal system is undermined by the nonsense that is the execution. Having the accused sitting in front of a digital judge assessing likelihood of guilt is an interesting idea, but the actual case needs a depth that simply isn’t present, and that flaw eats away at the setup with each new plot development.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

Chris is deemed preemptively guilty because he was caught on a doorbell camera fighting with his wife just prior to her time of death and was found in the aftermath black-out drunk at a bar. This is deemed more than enough evidence to see the man delivered the death penalty… until Chris is able to deploy his secret weapon: totally basic police work in the near-immediate aftermath of a crime! The protagonist’s progress toward exoneration sees him searching for others via digital footprint with the magic combo of motive and opportunity, and while I won’t spoil the various developments that unfold as he searches for the truth, the revelations are so textbook that one is left constantly more baffled by the computer’s extreme confidence.

On the one hand, the film does illustrate that computers could do a really bad job judging crimes, but it does so with elementary school-level concepts, and without the complexity in plotting that would be necessary to make its point, Mercy feels like it just gets dumber and dumber as it goes.

Mercy tries new things with screenlife filmmaking, but they don’t quite work as they should.

As far as style is concerned, I consider myself genuinely curious about the screenlife aesthetic (with notable titles including Open Windows, the Unfriended movies and the Missing and Searching duology). Mercy, however, can be described as a kind of hybrid, and it’s unable to quite click into what makes the movie in the format work – which is reflecting the way that people navigate the digital world in a familiar way. On the one hand, it’s interesting to see Chris bounce around modern communication methods to search for the truth behind what happened to his wife, but the science-fiction circumstances don’t allow the same kind of familiarity that makes the medium fun and special. Additionally, it has its own way of undermining the plot: if all of the evidence needed to exonerate Chris or at least generate acceptable reasonable doubt is discoverable via data, how is it that the artificial intelligence deems him guilty?

Ultimately, Mercy is a gimmick movie – the gimmicks being the new angle on screenlife filmmaking and the real-time storytelling – and I have no inherent problem with that, as there are plenty of solid features in cinematic history that hinge on unique approaches. The problem here is that those gimmicks are put on top of a rotten foundation, and that means that the work gets more and more broken as it continues to build. Save for you being abducted, locked into a chair and forced to watch it, it’s most definitely a film to skip.

Eric Eisenberg is the Assistant Managing Editor at CinemaBlend. After graduating Boston University and earning a bachelor’s degree in journalism, he took a part-time job as a staff writer for CinemaBlend, and after six months was offered the opportunity to move to Los Angeles and take on a newly created West Coast Editor position. Over a decade later, he's continuing to advance his interests and expertise. In addition to conducting filmmaker interviews and contributing to the news and feature content of the site, Eric also oversees the Movie Reviews section, writes the the weekend box office report (published Sundays), and is the site's resident Stephen King expert. He has two King-related columns.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.