Asylums are enigmatic places that are both frightening and intriguing. In movies, they either appear stacked to the brink with raving lunatics, or filled with people that seem no different than the rest of us. While Silence Of The Lambs was enough to terrify people into acting on their best behaviors, Girl Interrupted made the nut house look like a fun place to engage in slumber parties. Asylum takes a different route and shows that while institutions are good places to confine crazy people, a person’s own mind can often be their most inescapable prison.

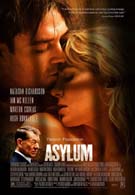

Asylum, the latest film from David Mackenzie (Young Adam), is about a married couple Stella (Natasha Richardson) and Max (Hugh Bonneville) who move to the grounds of a high-security psychiatric hospital for the criminally insane. Max has been appointed Deputy Superintendent and his promotion requires the couple and their young son Charlie (Gus Lewis) to live on the premises of his new facility. Trapped in a passionless marriage with an uptight husband who yells a lot, Stella begins to wonder if her happiness is on a permanent vacation. She becomes oddly drawn to a gardener/sculptor named Edgar (Marton Csokas), a tortured artist who has been confined to the asylum for years with little hope of dismissal. He is handsome and soulful, and their connection grows when they dance together at the annual loony ball. Before long, the two of them start using the greenhouse for more than gardening, and an illicit affair follows.

Stella soon becomes smitten with Edgar, and loses her grip on reality. Senior physician Dr. Cleave (Ian McKellen), with his own set of moral issues, specializes in sexual pathology and notices the connection between the two of them. He explains to Stella that Edgar is imprisoned for murdering his wife in a jealous rage several years ago, bashing her face the way he shapes a clay figure in the art studio. Instead of reacting like a normal person and calling off the affair, Stella becomes even more emotionally invested. Their romantic infatuation is far from healthy, but cannot be shaken.

The high point of Asylum is the film’s fantastic ensemble. At the head of this showcase is Csokas, who passes himself off like a sweet, wounded puppy, before he lunges at your face and gives you a nasty case of Rabies. He humanizes a criminal that could otherwise lack dimension and credibility. Richardson portrays her character with deep-rooted anguish and quiet desperation, capturing her inner turmoil. The problem is that Stella reminded me of the idiotic girls in horror movies where you keep screaming “No, don’t go in there!” as they walk repeatedly into death traps. Both actors play their faulty characters perfectly.

Like many thrillers, Asylum loses steam in the last third, as it crash-lands into an over-the-top, unintentionally comedic zone. The buildup is intense, and then tarnished by a series of events that feel disingenuous and scripted, particularly Dr. Cleave’s revelation. I felt like I was being tricked into feeling sympathy for false scenarios ripped out of a mid-afternoon soap opera, when the movie worked better as a love story between two people who everyone wanted to keep apart. Asylum is best classified as an interesting failure, but it succeeds as a cautionary tale to lonely housewives fantasizing about sleeping with the hunky gardener.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News