Interview: Bobby Fischer Against The World Documentary Director Liz Garbus

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

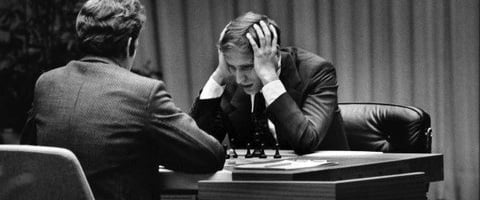

Premiering this Monday on HBO, Bobby Fischer Against the World is a new documentary chronicling the troubled life and unmatchable genius of chess player Bobby Fischer, whose 1972 match against Russian chess master Boris Spassky was front-page news and a symbol of Cold War era tensions between the United States and the USSR. Liz Garbus, whose previous films include the Oscar-nominated documentary short Killing in the Name and Street Fight, directs her documentary about Bobby Fischer in a way refuses to judge the reclusive and polarizing figure, even when discussing his saying "I applaud the act" after the 9/11 attacks on the United States.

I talked to Garbus in January at the Sundance Film Festival, where Bobby Fischer Against the World premiered and where she told me she was interested in making a film about such a famous and controversial figure precisely because he was such a difficult man. You can read excerpts from our conversation below, and learn more about the film at the HBO website. The documentary premieres this Monday, June 6, at 9 p.m.

Were you drawn to this story because Bobby Fischer is such a difficult figure, and not at all a typical hero?

I think the material is incredibly rich because he is incredibly complex. He's a difficult subject in some ways to get to know because he was so press-averse, so we had a challenge. But he's part of an American cultural history, and there had never been a complete accounting of his life. His life is an important part of American history, an important part of Cold War history, and is important in the canon of the artist-genius-madness.

Were there things you weren't able to get to in your research? Was there anyone, other than Bobby himself of course, who eluded you?

Boris Spassky was in ill health, so he wasn't part of the film. For a while I really, really regretted that, but then I realized had Boris been in the film and Bobby hadn't been, it would have become more of a Boris story. In a certain way that limitation allowed us to hone in more on Bobby.

Bobby had all these conspiracy theories about his match with Boris Spassky, that the cameras were bothering him, that people were plotting against him, and Boris seems really willing to go along with it. Maybe there really was something fishy about it.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

Well first of all Bobby has all his paranoid thinking about the match, and thinks that everything is stacked against him and the cameras are too loud. Now some can say it was theatrics to destabilize Spassky, that's a debate we deal with in the film. But by game six or soothing, when Bobby started to show his strength, Boris felt very weak. He felt there were bugs in the chair that might be emitting radiation, or something in the light fixtures. It was front-page news in the New York Times that they found two dead flies in his chair. It's not Boris's fault, not even Bobby's fault-- that was the Cold War era psychology. There was such distrust. That's what makes it such an interesting story because everything is heightened on that level.

This is such a specific part of American history, and it's so different from the way we think about things now. It must have been a challenge to recapture this world in which chess mattered to so many people.

Well Bobby is a product of a bipolar world. In so many ways. Chess is a bipolar game-- it's black and white, you has circumscribed moves. The Cold War was a bipolar world. Bobby re-emerges on 9/11 with those statements. His life was bookended by that, when all of a sudden the U.S. had this conflict with the War on Terror. That's when Bobby started to get very vocal again, talking about the U.S., talking about how we had it coming, etc. etc. Bobby seems to thrive in that bipolar context. And chess echoes that.

How much did you empathize with Bobby at the beginning of making this, and how much at the end?

I think the empathy grew. Some of the footage of him late in life, which I didn't have at the beginning-- watching that stuff of Bobby only made me grow in empathy for him. He called into radio shows-- that was his habit-- and we collected like 70 or 80 hours of Bobby just calling into radio shows, and we used excerpts of it. Listening to him ranting again made me more empathetic, because it was clear he was out of control-- his thought process ran amok.

Do you think people really overlooked his mental illness in getting so angry at him for his comments after 9/11?

In some of his radio phone-in shows he was talking about how the Jews wants to get rid of all elephants because their large trunks remind them of the uncircumcised penis. That's how far-out his thinking was. It's just a tragedy that this great mind was allowed to wander like that, and there was nobody who could pull him back in.

There's an element in the movie that's not explicitly expressed that the fame kind of pushed those delusions further. The attention increases the paranoia.

Shelby Lyman talks about that in the film. There were all these people around him that just wanted to be in his glow. And when you have all these yes-men around you, they're sort of enablers in a certain way. He never wanted to hear any other perspective. Anthony Sadie, one of his great friends, said to him, "If you stop playing chess, soon you're going to be alone. If you don't play chess, nobody is going to ask you to play chess." And Bobby couldn't listen to that. And it's true-- everybody still wanted him to play chess, but his lack of engaging in the chess world was his demise. The chess world is a very vibrant world, and he disappeared from it. And they all felt totally betrayed.

Staff Writer at CinemaBlend