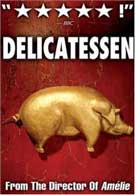

Delicatessen, a wickedly black French comedy released theatrically in 1991, marks the first collaboration between Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro, who later teamed to write and direct the equally bizarre City of Lost Children. In a grim future where food has become frighteningly scarce and cannibalism is no longer taboo, a former circus clown arrives at a dilapidated butcher shop/tenement in the midst of a burnt-out city looking for employment. Little does he know that its owner and his collection of oddball tenants are sizing him up for their next meal. When you enter the world of Jean-Pierre Jeunet, it becomes apparent very quickly that this place is unlike anything you’ve ever seen before and most likely will ever see again. The French director of such seminal films as Amelie and A Very Long Engagement takes quirky to the next level with his surrealist vision of life’s happy accidents. His tales rely on painfully elaborate set designs, outlandish characters with exaggerated features (and personalities), and a penchant for Chaplinesque slapstick to weave their strange magic.

Jeunet’s debut feature Delicatessen, co-written and directed by Marc Caro, gives us our first hilarious glimpse into this twisted universe. In the center of a bleak wasteland plagued by famine sits a ramshackle deli that doubles as an apartment building for a motley group of social misfits. As Clapet the butcher (a wild-eyed Jean-Claude Dreyfus) sharpens his cleaver, the camera careens down a dark passage to reveal the next item on the menu – an understandably frightened little man. It seems the prolonged food shortage has made it OK to feast on people, and soon the hapless victim is divvied up amongst the building’s denizens.

Lured by an ad promising work, Louison, a former circus clown (the diminutive Dominique Pinon, a fixture in all of Jeunet’s films), then arrives on the scene. His gentle demeanor and unfettered joie de vivre have a surprising effect on the ravenous tenants, especially the butcher’s daughter (Marie-Laure Dougnac) who finds herself falling for him. She soon enlists the help of the Troglodists, a bumbling underground resistance movement, to organize a daring rescue of her sweetheart, who’s blissfully unaware that he’s about to become dinner for his newfound friends.

Though at times uneven and a little too precious for its own good, Delicatessen undoubtedly has its share of delights. It succeeds more as a collection of impressive vignettes than as a cohesive whole, owing mostly to the inherent strangeness of the story. In Jeunet’s more recent offerings, his muse, the luminous Audrey Tautou, provides the necessary emotional core at the heart of the deliriously romantic Amelie and the WWI epic A Very Long Engagement. Without her, we marvel at the impressive visuals and laugh at life’s absurdities but lack any real connection to the proceedings. She is undoubtedly the Uma to his Quentin (or Dietrich to his von Sternberg if you prefer a more classic analogy).

That’s not to say that Delicatessen doesn’t contain surprising moments of tenderness in the midst of all the madness and black comedy. Pinon’s hangdog features and gift for physical comedy infuse many of his scenes with a quiet poignancy. He mesmerizes two little boys with a bubble-blowing exhibition, plays the musical saw in a haunting duet with Clapet’s daughter on cello, and, in the film’s most quietly affecting sequence, bounces on squeaky bedsprings with the butcher’s mistress (Karin Viard) in rhythm with a Hawaiian musical number on a nearby television set.

The bedsprings come into play in another delightful scene as the percussion in an impromptu symphony involving everyone in the building. This kind of inspired choreography and skilled editing transforms the deli into one giant Rube Goldberg-like mousetrap. A woman devises incredibly elaborate suicide attempts only to see them foiled at the last moment. One tenant sells “bullshit detectors” while a pair of brothers manufacture the toy cans that make cow noises in their cramped apartment. The inept band of sewer-dwelling Troglodists fails miserably at every juncture of its rescue operation. It all culminates in a chaotic finale that would make Buster Keaton proud.

For a first feature, Delicatessen is an impressive technical achievement. Although slightly claustrophobic (and maybe intentionally so) because of its single setting, it looks great, thanks to Darius Khondji’s cinematography, which drenches every scene in reds and browns, giving the film the appropriate dingy, wasted look of apocalypse. Although absurdist French humor may not be everyone’s cup of tea, it’s undeniably fun to sample this tasty comic treat as a precursor to Jeunet’s later, more fully realized works. The extra features on this disc are unfortunately lacking because of Marc Caro’s refusal to participate in the commentary and his insistence on having his contributions excised from the documentary features. Caro and Jeunet parted ways after City of Lost Children and apparently it wasn’t an amicable split. That’s regrettable because Jeunet takes great pains to credit Caro whenever possible for his contributions to the film.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

The DVD version includes the original theatrical trailer, which is actually just one entire unedited scene from the film - the previously mentioned squeaky bedspring symphony. It’s a great idea to market the movie this way because that sequence is such a virtuoso piece of inventive filmmaking. I’d go see the movie based on those two minutes alone. Also included are several ten-second teasers that are pretty effective in their own right.

“Fine Cooked Meats”: A Nod to Delicatessen contains roughly fifteen minutes of footage from the set unaccompanied by narration. The result is at times compelling when the documentary camera is focused on the intricate behind-the-scenes preparation but mostly redundant, since it usually captures the actors from the precise angle at which they’re being filmed. Essentially we get a video version of what we just watched during the feature without the benefit of cast and crew interviews. Obviously, these “making-of” features weren’t the norm in the early Nineties like they are today and I’m sure it would have been tough to try and assemble everyone together just to reminisce for a DVD release.

“The Archives of Jean-Pierre Jeunet” offers a number of audition tapes, including those of the two leads, Pinon and Dougnac. It also contains footage of the only exterior built for the film, the rooftop of the deli where the climactic battle takes place. At the end, we see the footnote stating Caro’s refusal to participate.

Jeunet’s commentary accompanying the feature, which is also subtitled because he only speaks French, illuminates several interesting aspects of the production. An offhand comment made by his girlfriend about the butcher in their building was his original inspiration for the film. He also shares a few of the maxims that have shaped him as a director. For instance, Jeunet insists on screen-testing every actor, is always dissatisfied with footage from the first days of a shoot, and admits that it takes years for a filmmaker to view his own work like a normal audience member without picking apart its flaws.

He also shares a technique he uses frequently to keep the actors on their toes. During rehearsal and sometimes even during the filming of takes, he’ll instruct one actor to improvise without telling the other, causing a more spontaneous reaction in the latter. Poor Marie-Laure Dougnac, who plays the butcher’s daughter, seems to be Jeunet’s most frequent target, including one scene in which he instructs an actor to actually slap her instead of faking it. The painful blow produces real tears that were used in the finished film. Jeunet seems simultaneously proud and remorseful upon seeing it again.

There’s also plenty of discussion of lighting, storyboarding, and editing of the complicated sequences that populate the film. Jeunet provides an education on the use of short-focus lenses to make his actors more expressive and also gives a shout-out to Darius Khondji, the renowned D.P. who contributed to his later films as well. Without this insightful commentary, there’d be little to recommend about the DVD special features.