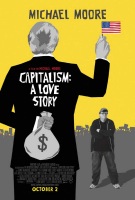

It’s easy to write off Michael Moore as a Democratic pundit, in the same category as dudes like Al Franken and Kurt Olbermann. And sure, with films like Fahrenheit 9/11 and Bowling for Columbine under his belt, it was a fair accusation. But Capitalism: A Love Story reaffirms, as Sicko did before it, that Moore is a man of the people. He’s less a voice for the blue states and more a representative to those who outnumber the powerful few by millions, yet somehow still have nothing to show for it.

An early scene in Capitalism has a recently evicted blue collar worker state something to the tune of “it’s only a matter of time before the people who ain’t got nothing start a rebellion against the people who got everything.” This ends up being a central theme that the film revisits throughout its two hour running time. And by film’s end, we realize just how true these words are, just how vital they are to Moore’s argument.

To get there, Moore first displays the blatant mistreatment of lower class citizens by corporate big wigs. There’s a judge who knowingly sent innocent kids to jail in order to help boost the profits of the private detention facility he was sending them to. Of course, the company handsomely rewarded the judge financially. Another example shows how, while middle and lower class would-be homebuyers were being offered deadly subprime loans, our representatives on the Hill (including Chris Dodd) were having their fees and paperwork waived, receiving millions in nearly headache-free loans. The most scathing of these examples, though, is what we find to be called “Dead Peasant Insurance,” an insurance program that allows employers to take out life insurance plans that, in the event of the death of an employee, pay out thousands, even millions of dollars to the company. The employee’s family never sees a dollar of this cash. In essence, these employees are more valuable to the company dead than alive.

And so this is Michael Moore’s love letter to capitalism, a damning analysis of the corporate greed that is supposedly the core of the ‘American Dream.’ A little hard work and passion leads to success, right? Well, no. Not when the few at the top do everything in their power to hold down the bottom. Michael Moore’s love letter ends up being an impassioned break-up letter, a letter than even Catholic priests and bishops get in on, taking their own shots at capitalism with their religious interpretations of the economic system. Republicans and Democrats alike join together to express their grief at the problems at hand. A woman with a George W. Bush commemorative plate cries about the way her husband’s company treated her family.

But this is a Michael Moore movie. So everything has to be taken with a grain of salt, right? Moore is known to be a bit liberal with his editing and tends to overlook facts that don’t fall in line with his thesis. That may be true here as well, but the thing is, he isn’t arguing for anything extreme. He isn’t arguing for gun control. He’s not trying to sell universal healthcare. He’s merely trying to show us that there is a microscopic group of people who currently hold 90% of a pizza and all of the power behind what goes into making that pizza. And we, the people, the millions, have one tiny slice of pizza and no say in what toppings go on it. He wants the people to have their fair share of pizza and the option to not have any mushrooms on it. So as with any documentary, the movie comes from a perspective that can at times be heavy-handed, but his intentions are sincere, and that’s what’s truly important.

If the film has any missteps, it’s in its explanation of the current economic crisis. Like just about everyone, Moore seems to have trouble putting it all into language that can be understood by a common person. At times the sections bent on laying out the crisis in layman’s terms end up being the sections that drag, leaving Capitalism: A Love Story far less focused than Sicko. Good ol’ Mike has never been all that great at displaying hard facts; his true talent lies in the regular people he finds to help make his argument. And that’s exactly where this movie shines. We feel for the workers in the plants that get laid off. We feel for the woman whose husband died and whose employer made $5 million off of his death. We feel for the family that’s treated like criminals for having been evicted from their home. Just as Moore wants the country to be, he puts the power in the hands of his subjects.

Given its subject matter, it would be easy to label Moore as a Socialist sympathizer, but as we learn throughout the movie, Moore does not want Socialism any more than any Sarah Palin supporter. Instead, he wants an economy that more closely resembles our government, a place where every person has an equal hand in his or her well-being. He wants democracy. He wants the people to be the voice behind what’s their wallet. And if you can argue with that, then you’re probably part of the problem.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News