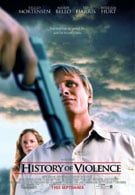

Tom Stall (Viggo Mortensen) is a gentle, soft-spoken, almost painfully ordinary man from a quiet, almost painfully ordinary small town, and he has a secret. In fact, it may even be a secret from him. Tom it seems, is good at violence. Very good indeed. But this isn’t a Jet Li movie and though his surprising abilities are considerable, that’s not the point. A History of Violence isn’t interested in being an action flick; Tom’s skill with a gun is ancillary to the film’s exploration of how this revelation affects him and those he loves

Violence begins with gratuitous murder. Two men, one dressed in so much black he has to be a villain, and another dressed like a wandering college-aged hitchhiker, murder the staff of the motel where they’re staying instead of paying the bill. Just to make sure we know they’re really super-evil, for kicks they shoot a little girl. The killers drive off, but we know we’ll see them again soon.

Enter the Stall family. Tom runs a diner, his wife is a lawyer. His son is the school geek, and sucks in PE class. Cronenberg is desperate to break away from Hollywood movie cliché and show us actual people and so spends a good portion of the beginning of his film attempting that. But there’s a problem. I don’t think Cronenberg has any concept of what normal people are like. His vision is a slightly skewed one, like looking at real people through the lens of someone who’s lived so long with the power, wealth, and fame of being a filmmaker that he’s lost all touch with what most of us consider the “real” world.

Take Tom’s son Jack (Ashton Holmes) for instance. He’s supposed to be the school wimp. He gets picked on, beat up, and made fun of. He’s terrible at sports, and relies on his quick wit to get him out of trouble. Popular? Hardly. But it’s strange… because he looks like he just fell out of the cast of the “O.C.” The character may be written as a normal, everyday wimp, and Cronenberg wants us to see that, but the person he’s cast to play the character is anything but. He’s a stunning physical specimen, the type that always gets the girl, the type that excels at sports, the kind of kid that gets elected homecoming king, not shoved in a locker. This problem extends to his classmates as well. They all look like perfect Hollywood actors, as if they just rolled off an assembly line on the New Line backlot. I realize that they are actors, but in a film where you’re trying to show us normal, everyday people dealing with violence it’s a little jarring to see a PE class composed of nothing but tall, thin, well-muscled, perfectly fit teenagers. Sure, they’re riding around in beat-up pickups and acting out the parts of fat kids, nerds, rednecks, or losers… but they’d all be more comfortable on the runway of a fashion show.

This problem permeates every frame of the film, and watching it leaves you with the unshakable feeling that something here is just slightly off. Tom and his wife Edie (Maria Bello) have sex, and give Cronenberg some credit here; he deliberately avoids the usual romanticized, boring, missionary sex that most movies use. He tries to give us a little picture of what real, long-term marriages are often like. Tom and Edie have been married a long time, but they still have sex. If they did nothing but missionary, they’d have been sick of each other long ago, so Cronenberg stops for a little sequence where Edie dresses up as a cheerleader and then she and Tom 69 while the house is empty of kids. Gutsy, and in a way refreshing choice. But later, when things get tough, rather than locking themselves in separate rooms as real people might, Tom and Marie engage in violent sex on the stairs… of the type that only works in movies. A History of Violence a bizarre world of strange, ill-fitting pieces. Later in the film, once things start getting hairy, this becomes a little easier to ignore, but it never vanishes. For as hard as Cronenberg tries to avoid the Hollywood cliché, the movie feels like he’s been stuck in a filmmaking vacuum for so long he’s no longer properly able to differentiate between fantasy and what the world is like out here for the rest of us.

Because of that, the beginning of the film drags as we follow this weird (and sometimes poorly acted… I’m looking at you cute, blonde, Dakota Fanning wannabe) family around in their daily lives getting to know them. Finally, something happens to change them. The brutal serial killers from the beginning of the film show back up, this time at Tom’s diner. They put a gun to his head and start raping his customers. Tom, usually mild-mannered to a fault, responds like Jean Claude Van Damme. In a flurry of brutal, sometimes over-the-top action, he kills both men. He looks like a professional. Maybe he is.

The community lauds him as a hero, his face is splashed all across the news, and then life goes on as usual until one day three men in slick suits show up at his diner. They’re mobsters and they insist that he’s a professional killer from Philly named Joey. Tom and his wife are frightened and shocked. Tom insists that not only does he have no idea who Joey is, he’s never been to Philadelphia. But who is telling the truth? How does he explain his exceptional talent for violence and death? Why does his wife put their 6-year-old daughter in a child seat meant for a baby? Ok, ignore that last question, it’s a little off track.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

The meat of Cronenberg’s film is spent watching the characters he’s struggled so hard to build deal with the consequences of what may or may not be Tom’s past. It’s here that the movie actually hits its stride, when it forgets about trying to be “real” and simply lets itself go in a fairly unique, and interesting premise. Viggo is a natural at playing quiet, dangerous men, and he’s brilliant as the often confused, violently skilled family man Tom Stall. Maria Bello, who has never heard the words “no nudity clause”, is capable as a wife trapped in the middle. Notable is William Hurt, who pops up towards the end in an interesting cameo role. He’s notable, mostly because you may not notice that it’s William Hurt. The character is completely against type for him, but he’s fantastic nonetheless.

Ultimately, A History of Violence is a maddeningly frustrating film. The premise is a good one, and Cronenberg goes through the motions of doing all the right things to make it work. He takes his time to contrast the sleepy, normal world of a small town family with the violent, brutal one into which they’re being dragged. He takes great pains to avoid the obvious, lazy choices that other lesser directors might have made. But it doesn’t always work. The man simply seems out of touch, and the result is a movie that to him might ring true, but that to the rest of us living in the normal, starlet-free world he’s trying to enter, feels ever-so-slightly skewed. It would be easy to blame this all on bad acting from supporting characters, or a shallow script. But that’s not what’s going on here. There’s a gripping, intense experience buried in History of Violence, but Cronenberg’s embarrassing and awkward unfamiliarity with normalcy degrades it.