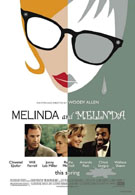

I don’t get Woody Allen. I’m not a nebbish New Yorker, though being one looks pretty cool. In fact, in the future it’s something I might aspire to. But for now, it’s not something I can relate to. Because of my age I’m also not old enough to remember when he was relevant, since for most of my cinematic awareness he’s been making nothing but bad films. To me, he’s the guy who made Curse of the Jade Scorpion. No thank you. Unlike his other recent work, Melinda and Melinda offers a glimpse of why people used to think Woody Allen was so good. It helps that he isn’t in it.

The film’s premise is stripped down and self-congratulatory, as it opens on a little café wherein a group of screenwriters sit at a table debating which is the true essence of the human soul: comedy or tragedy. To prove their point, two writers decide to tell the same story, from their own unique writing perspective. The comedy writer (Wallace Shawn) tells it as a potential laugh factory, the tragedy writer (Larry Pine) from the downbeat, dramatic perspective he thinks in.

Melinda and Melinda’s first problem is that it doesn’t stick to its fairly simple premise it sets forward. The stories told aren’t really the same. Both begin with a woman named Melinda (Radha) interrupting a dinner party, but other than a few superficial nods the similarities end there. That’s something of a shame, since I like the movie’s premise well enough to want to see how telling the same story from two perspectives would turn out. Despite claims to the contrary, that’s not what you’re getting. The premise is an excuse to cram two movies into one, and that’s about it. There’s no big revelation on the true nature of the human condition to be had.

The tragic story has Melinda interrupting a group of friends. She’s arrived to stay with them, two months later than she’d said she would. This Melinda is a dangerous wreck: suicidal, addicted to pills, a heavy drinker recently released from a mental institution. She moves in with her married friends Lee (Jonny Lee Miller) a struggling actor and Laurel (Chloe Sevigny) a music teacher. It’s this story of how a mentally ill Melinda attempts and inevitably fails (this is a tragedy after all) to put her life back together that occupies most of Melinda and Melinda’s running time. Or at least it feels like it does. The dramatic sections drag; the characters are unlikable and seem listless next to the much livelier and interesting comedic segments, featuring the lovable Will Ferrell.

The comedic section, despite being kicked off by a dinner party interruption from a somewhat similar but by no means the same Melinda (still Radha Mitchell) focuses almost entirely on Will. That makes sense since Ferrell not only really funny, but he’s playing a role that was quiet obviously meant for Woody. But Woody is an old curmudgeon, and has finally realized it’s high time he got off the screen. Enter Will, saying Woody’s lines and doing a fantastic interpretation of Allen himself. He’s a (surprise) nebbish New Yorker, and also in this case an out of work actor. His wife (Amanda Peet) is a successful and sexually frigid director. Melinda is their downstairs neighbor, and when she barges into their lives Will’s character Hobie strangely falls for her. He takes her to the track with Steve Carrell (who is inexplicably not allowed to speak) and magic happens… for him at least. The story is funny, familiar, and awkward. Woody brings his “A” game here and you’ll find yourself wishing this had been the entire movie, instead of only half the story.

This is half of one of the best Woody Allen films in at least a decade. The other half is simply some junk that got in the way. That leaves Melinda and Melinda as a frustrating experience, but one that’s worth enduring. Will Ferrell is a perfect Woody Allen avatar, let’s hope Woody realizes it.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News