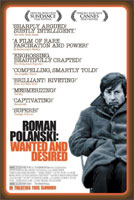

The details of Roman Polanski's strange, eventful life have been retold and parsed so many times, they're part of the cultural lexicon as much as his definitive films are. So the tactic Marina Zenovich employs in her documentary, Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired, is subversive by way of its objectivity. Zenovich reports, with little editorializing, the facts of the 1977 trial that led Polanski to flee the country permanently, a fugitive to this day. And the details, as minute and difficult to understand as they are, are so shocking and bizarre, they overshadow even the most outrageous aspects of Polanski's actual crime. The result is a clever, contemplative kind of courtroom drama that utilizes the best of Hollywood filmmaking style to tell a story so strange, it must be true.

Polanski has been pegged by detractors as a "child rapist," but the actual details of the crime are more complicated. Having made his name with dark films like Rosemary’s Baby and Chinatown, as well as having suffered the murder of his wife, Sharon Tate, in 1969, Polanski was already a mercurial and strange figure in Hollywood when he asked to photograph 13-year-old Samantha Gailey for a French edition of Vogue in 1977. Gailey and Polanski disagree on the details, as cleverly displayed in the film through police transcripts, but Polanski eventually pled guilty to charges of unlawful sex with a minor.

It’s in the courtroom where the story gets really interesting, but also too complex to fully describe in this review. A series of backdoor deals and plea bargains at first looked to free Polanski with little more than a slap on the wrist, but as media scrutiny of the case escalated, Judge Laurence J. Rittenband seemingly decided that the attention mandated a harsher punishment. Though Polanski’s attorney Douglas Dalton and the prosecuting district attorney Roger Gunson were on opposite sides of the fight in ’77, the two agree in the documentary’s interviews that it was Rittenband’s desire for media attention that turned the trial into a circus, rather than justice.

Though Roman Polanski is a story about the many people who surrounded the case, from Gailey—now a married mother of three who says she forgives Polanski—to the various colorful reporters involved, what emerges is a nuanced portrait of the man in question, so much more than the criminal many of us are willing to peg him as. In archival interviews, Polanski admits frankly to liking young girls, but in the same breath makes it clear the turmoil all the press attention caused him. Archival photographs and video, from both the trial and the time of Tate’s murder, vividly illustrate the toll of a life lived on display. Uninterested in discussing the undeniably icky details of Polanski’s crime, Zenovich makes a compelling argument that a guilty man who escaped sentencing may still have been overpunished.

Zenovich makes clever use throughout the film of clips from Polanski’s film, as well as a haunting piece of a short, silent film he made, in which he played a boy dancing to the beat of a drum pounded by an old man in a chair. The clip comes at the point when it becomes clear how much Rittenband, who died in 1994, manipulated Polanski’s case for his own self-promotion. Though Polanski is many things—as an interviewee says near the end, in his adopted home of France he is desired, and in America he remains “wanted”—Zenovich asks us to see him, however briefly, as that boy refusing to keep up with the dictated beats.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

Staff Writer at CinemaBlend