Mad Max: Fury Road Shouldn't Exist, And That's Why It Should Win Best Picture

The final results that we see on the big screen often do their best to hide it, but the truth of the matter is that every Hollywood production is a struggle. Every stage of the process presents cut backs and negotiations; there’s an incredible amount of physical and emotional effort that goes into the set-up of every scene; and the whole thing can all be so long, repetitive, and drawn that everyone involved, by the end, can’t help but feel mounting frustration. The Academy Awards have never been shy about appreciating this harder side of filmmaking in the past, and the truth is that all of this year’s Best Picture nominees surely went through their own complications and strife through filming. (We're looking in your direction, The Revenant.)

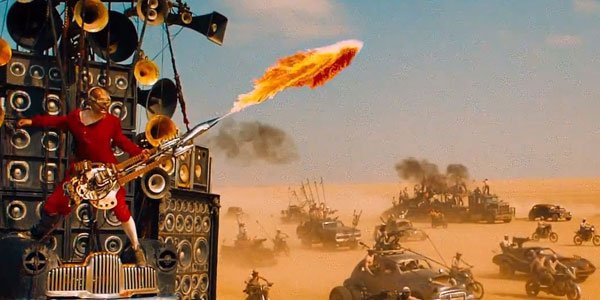

No titles, however, can compare in this arena to what went into the process of making writer/director George Miller’s Mad Max: Fury Road - a film, from a macro perspective, that is a miracle of existence given all of the roadblocks and complications that were involved in its making. The full story of its strife is only made more amazing when watching the blissful, awe-inspiring finished product, and it’s in the contrast between the two that the great blockbuster emerges as the only choice to win the top prize at the Oscars this year.

Mad Max: Fury Road was always going to be considered a delayed sequel – as Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome came out all the way back in 1985 – but there was a time when the fourth movie in the series could have actually been a ‘90s film. Director George Miller (also nominated this year for his efforts on Max) got the rights to the franchise in 1997 and was developing ideas the following years. So why did it take about 20 years for anything to happen? Well, it was a mix of various things not limited to: a dropping American economy after September 11th; tightened shipping and travel regulations; the Iraq War; and rain so heavy in the Australian desert that flowers bloomed and ruined the wasteland aesthetic. All of these things would legitimately cause a filmmaker with less fortitude to toss up his or her hands and just call it quits, receiving the message that some projects aren’t meant to come together. But George Miller really wanted to make Mad Max 4.

Of course, even after the film managed to get cameras consistently rolling, the issues didn’t stop. Miller had a clear vision for the movie – seeing it as just an extended chase sequence with limited dialogue – and that vision just so happened to not require the need for a script, just a long series of detailed storyboards. This clearly suited the writer/director just fine, but he had a harder time getting some members of the production on board – specifically stars Tom Hardy and Charlize Theron. The combination of the rough conditions in the Namibia desert and perceived lack of organization led to mounting frustrations and increased tension, making the set of Mad Max: Fury Road not all that pleasant (by most accounts). But why do we know about this? Because Hardy and Theron were so personally awed by the finished cut that they publicly apologized to George Miller, and Hardy even went as far as to paint a specially-inscribed self-portrait to give to Theron as an act of contrition. They realized their conflicts and behavior were petty in the majesty of such incredible art. That’s right: Mad Max: Fury Road so incredible, it actually fostered peace.

You’d think that a film dealing with long delays, major location changes, bickering co-stars, budget issues, and seriously rough environments really should show some kind of wear and tear, but it's imperceivable in Mad Max: Fury Road - which is about as clear a representation of organized chaos that we likely will ever see on screen. The narrative is as simple as they come (heroes run away from bad guys; heroes turn around and come back), but what’s built on top of that is really filmmaking perfection. It’s not packaged like the typical film that Oscar voters cast their ballots for, but it’s visually stunning, and makes use of color better than most high drama. And while Mad Max pumps the energy to 11 and keeps it non-stop throughout, it never feels exhausting, and you immediately want to go for another ride as the credits roll.

As all great science-fiction does (a genre that’s been tragically looked over time and time again by the Academy), Mad Max: Fury Road also plays with some fascinating themes relating to our modern world, while also launching a wonderful and brilliant debate about the nature of fear versus hope. All wrapped in with immediately iconic characters and shockingly high stakes for its simple structure. All together, it's a masterpiece.

Had Mad Max: Fury Road merely been good, we would have still had a greater appreciation for it because of all the hardships the production endured, but that’s not what we’re dealing with. George Miller looked at what the universe was clearly trying to tell him was an impossible movie to make, metaphorically flipped the universe the bird (or perhaps literally – I don’t know), and persisted to work with his cast and crew to make what will long be considered one of the greatest cinematic experiences ever. There really is no prize that the movie shouldn’t win, and that includes Best Picture at this year’s Academy Awards.

CINEMABLEND NEWSLETTER

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

Eric Eisenberg is the Assistant Managing Editor at CinemaBlend. After graduating Boston University and earning a bachelor’s degree in journalism, he took a part-time job as a staff writer for CinemaBlend, and after six months was offered the opportunity to move to Los Angeles and take on a newly created West Coast Editor position. Over a decade later, he's continuing to advance his interests and expertise. In addition to conducting filmmaker interviews and contributing to the news and feature content of the site, Eric also oversees the Movie Reviews section, writes the the weekend box office report (published Sundays), and is the site's resident Stephen King expert. He has two King-related columns.