Ong-bak opens with the world’s most brutal tree climb. Dozen’s of men claw, scrap, and frantically climb their way up a massive tree. They kick, and push each other as they climb, desperate to be the first to the top. The scene is unflinchingly brutal, as shirtless ascenders frequently plunge from its branches, banging their heads and breaking their backs before they fall with a hollow thud on the loose dirt below. Those who hit the ground are not quick to get back up. This is the opening ritual in the celebration of Ong-bak, a festival held in a small Thai village every 24 years to celebrate and worship their local deity, a man-sized Buddha statue for whom the festival is named.

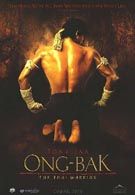

The first man to the top is Ting (Tony Jaa), and that bone crunching scaling is only the beginning for him. In the midst of the tiny village’s festival preparations, a greedy gangster from Bangkok named Don, cuts the head off the Ong-bak statue, escaping with it back to the city. Young Ting, having been trained by the village’s most skilled Muay Thai (a local form of martial arts) teacher, is sent by his people to retrieve their god. Some of this is a little unclear. Why for instance would Don steal the head of a valueless, lumpy statue? But the nitpicks are irrelevant, since this is all just setup to showcase Tony Jaa’s astonishing fighting skills.

Ting arrives in the Bangkok, an out of place hick in a gang infested world of drugs, motorcycle races, and fighting for money. There, he looks up his cousin George (Petchtai Wongkamlao). Ting needs help to find Don, but instead of showing him the way, George lures him into fighting for money, dangling promises of aid like carrots. George is like Sammo Hung to Ting’s Jackie Chan. He’s the fat sidekick who spends a lot of time huffing and puffing.

Paralleling Tony Jaa to a young Jackie Chan is a pretty fair comparison, once the fighting starts Jaa and his cast of stunt-fighters pull of amazing, vicious fight choreography, gleefully reminiscent of Drunken Master, and maybe even the best martial arts film ever made, Drunken Master 2. There are no wires, no CGI, and from what I can see no mats; just perfectly skilled performers executing intentionally ferocious, graphic moves. Ting never settles for a kick to the gut, he punches his opponents right in the head. No one encounters Ting without at least getting a concussion. Bodies are smashed and thrown about with such realism and regularity, it’s impossible to picture the making of this film as anything other than a long trip to the hospital ward.

The fights are fantastic stuff, the only problem is director Prachya Pinkaew knows it. He’s almost too in love with the wildly creative work Jaa and his crew are pulling off. Bound and determined to get the most out of every kick, the most exciting, jaw-dropping moves in the film are replayed over and over, sometimes replayed as many as four times right in a row, from multiple angles and multiple speeds of slow motion. It’s a colossal mistake. The real excitement in watching bewildering fight choreography like this is in being surprised by what the fighters pull off next. Part of the brilliance of Drunken Master 2 for instance, is the rapid pace at which Jackie Chan pulls off so many impossible feats. Ong-bak’s martial arts are nearly as eye-popping, but Pinkaew takes most of the fun out of them with his play-it-again approach. It quickly becomes annoying, and halfway through the film I found myself yelling to no one in particular, “Cut it out!”

The movie itself however, is quite serviceable. The cinematography is dark and gritty. The story of a fish out of water farm boy kicking ass in the city is solid enough as a setup. The music is a strange but cool mix of techno-inspired beats and what sounds like a traditional Thai mix. Pinkaew’s tendency to batter the audience over the head with Jaa’s best stunts can’t completely ruin the flat out fun to be had in watching a movie like this. It’s such a relief to see a martial arts film without the faux floating and ridiculously looking battles that emphasize stylistic concerns over enthusiasm. I’m tired of seeing highly skilled warriors battling with their hearts in ancient China. It’s nice to see a film set in the modern world that lets its combatants punch each other in the skull. When it comes to skull punching, Tony Jaa is supremely talented in a way I haven’t seen since the golden age of Jackie Chan. What’s most electrifying about Ong-bak isn’t the film itself, but envisioning what Tony Jaa might do next.

Most Popular