Blind PSVR Review: Stumbling In The Dark

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Considering the fact that gaming in virtual reality requires the player to strap a clunky device to their head, I'm surprised more developers haven't built experiences around altering the player's sense of sight. But that's exactly what the team at Tiny Bull has done with Blind, tasking the player with solving puzzles and exploring a spooky mansion with limited vision.

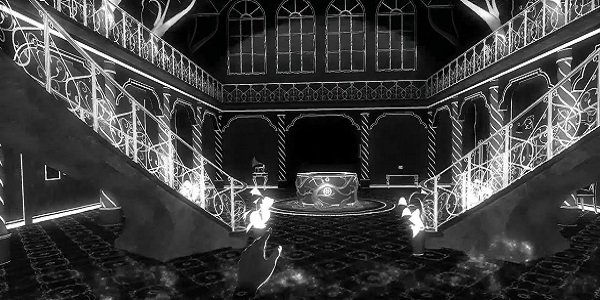

Blind opens on a dark and stormy night as a young woman, Jean, drives down a rain-spattered road with her scared brother, Scott, in the passenger seat. Next thing you know there's a crash and Jean wakes up to discover she no longer has the full use of her sight. After stumbling around a bit, Jean learns that she now has a sort of echolocation to guide her, briefly painting the world around her in a striking black and white as sound waves echo out from their source.

Before long, Jean gets her hands on a cane she can use to tap the ground, making it easier to find her way around a mansion that perhaps isn't as unfamiliar as she originally thought. To keep players from going overboard with the cane, Tiny Bull built in a system that will sort of overload Jean's senses if she creates too much noise.

As a quick note, I initially tried playing Blind with Move controllers and quickly switched over to the much better standard controller. The game utilizes 30-degree turning rather than smooth movement and you can't really map that too well to the Move controllers, which lack analog sticks. Movement is much more natural on a standard controller, with the cane mapped to the left trigger and grabbing environmental items mapped to the right trigger. The cane is even analog, meaning a light press of the trigger will produce a more subtle wave of vision while a hard press will create a bolder, longer-lasting view of the world.

Jean eventually meets The Warden, a mysterious, masked character who seems to hold all of the answers about what is going on and is only willing to share them with Jean if she manages to solve a bunch of puzzles and escape the mansion. There's clearly more going on here than what we semi-see on the surface, and earning those answers from The Warden and Jean's own memories -- which pop into scenes like ghostly apparitions -- serves as a solid motivation to keep looking for ways to unlock more of the mansion's secrets.

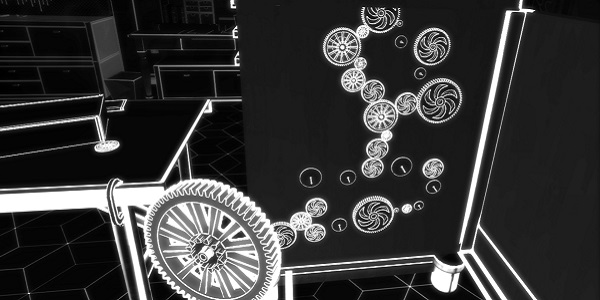

The puzzles themselves, though, lean too heavily on genre tropes and don't take full advantage of Blind's unique mechanics as frequently as I would have liked. You'll need to set a clock to a specific time to get a key, for instance, or place some gears in the proper sequence to get an old jukebox to start working again. From placing specifically-shaped items on matching pedestals to turning nobs to line up a combination and open a door, Blind definitely sports some classic Resident Evil vibes.

One of my issues with Blind is that the puzzles were occasionally too obtuse for their own good and resided in a world where the rules weren't consistent. That clock puzzle mentioned above gave me an especially frustrating amount of trouble when one clue seemed to point to a very specific answer (that made perfect sense), but a bit of info in another clue (that kind of breaks the logic of the first clue) was necessary to actually complete the task. That's vague, I realize, but since this is a puzzle game I don't really want to get too far into spoiler territory.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

A later puzzle requires the player to spin some dials to set a combination based on a large sequence of images nearby. The fact that the puzzle is image-based was confusing, since those types of details (you can see a frame but not a picture in the frame, for instance) are missing in most places around the mansion. So why can I suddenly see writing on a chalkboard? Worse yet, I fully admit that I absolutely botched my way through that particular puzzle. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn't figure out the solution the game was trying to point me toward. With my PSVR strapped to my head, I couldn't work through the problem on a piece of scrap-paper and, due to the limitations of the tapping, taking a long look at the complicated image meant I had to sit there and quietly tap the cane literally every half-second. Even when I randomly set the proper code and the door opened, I couldn't understand why that particular combination was the answer.

The lack of consistency in rules is on display throughout Blind. Some rooms require you to pull books off of a shelf to discover a key item or hidden object, while others can't be interacted with. Some drawers and cabinets open while others don't. Some objects can be grabbed and thrown while others can't. The result is that I spent much of my time in Blind playing it like an old adventure game, investigating every square inch of an environment to make sure I wasn't overlooking something that, in this particular room, was actually important.

Those issues actually spill over to the narrative in one jarring regard, too. I won't go too deep into details, but you eventually learn that a series of plot points has been used as a red herring to keep the player guessing. The problem is that, given the game's resolution, the existence of those plot points (and some other revelations) no longer makes sense.

If it feels like I'm being harsh, it's only because I feel like Blind was so close to being a great game. I enjoyed the majority of the game's puzzles, even if they were a bit routine. The monochromatic mansion itself is lovely to look at, though the hook of having limited vision quickly fades from being an interesting wrinkle to feeling more like a frustrating hurdle. Sound is also well utilized, with various objects in the world helping guide the player or add landmarks to the surroundings. And while I would never call Blind a horror game, there are some genuinely creepy moments spread throughout its intriguing narrative.

My big issue with Blind is that puzzle games are inherently frustrating and, too frequently for my tastes, several of the game's issues would manage to needlessly compound that frustration. The puzzles were occasionally too obtuse for their own good or too simple to feel rewarding. And while the narrative was certainly intriguing, some of the voice acting made me feel like I was witnessing bad community theater rather than a psychological thriller.

Despite all of that, I enjoyed much of the time I spent in Blind, doing my best to memorize my surroundings in quick flashes of sound and trying to piece together what, exactly, was going on. Since VR is still mostly uncharted territory, my willingness to overlook frustrations was heightened by my desire to experience something new. There are a lot of interesting ideas on display in Blind and, as a short-lived puzzler that clearly had a lot of heart poured into it, it's worth checking out.

This review based on a PlayStation VR download of the game provided by the publisher.

Staff Writer for CinemaBlend.