Interview: Mike Newell And Scott Steindorff

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

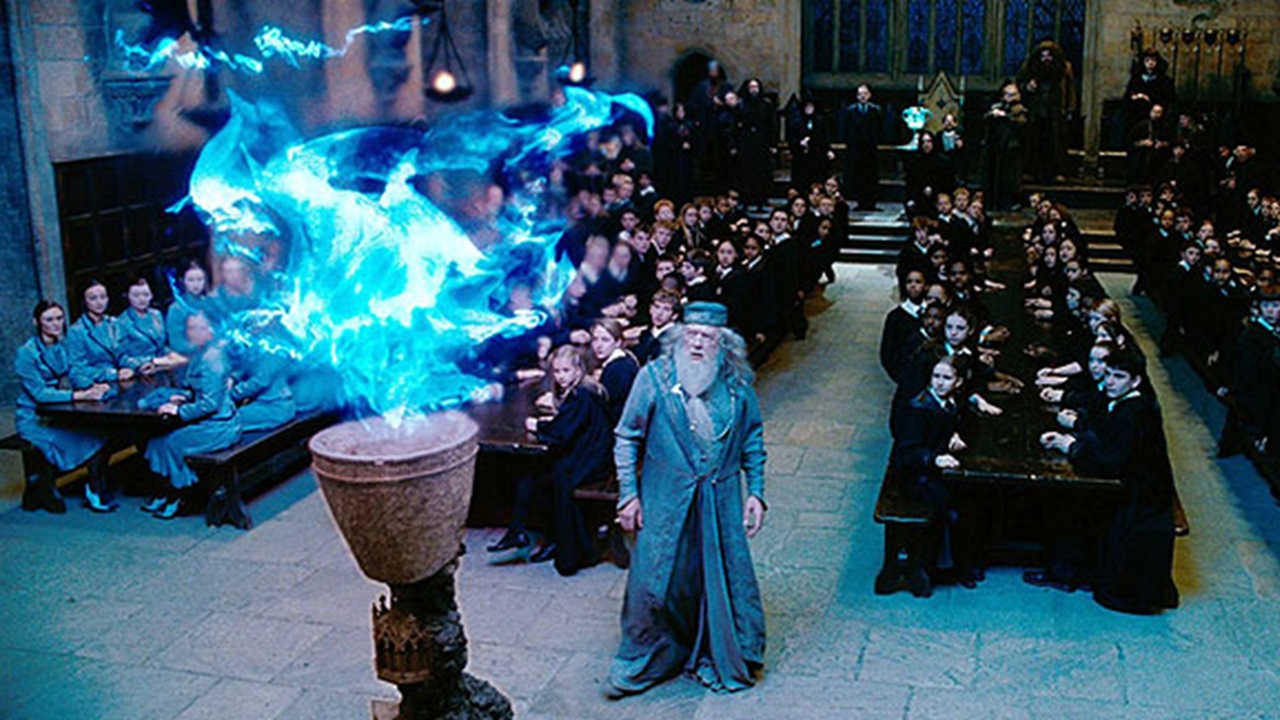

Mike Newell has traveled some pretty impressive distances for his last few films. In 2005 he found himself in the enchanted Hogwarts castle, directing the fourth installment of the Harry Potter series. Now he’s in Colombia, a country he swears has less danger and more charm than they tell you, for Love in the Time of Choleraan adaptation of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s classic, epic love story. He may have had a tough time dealing with Potterphiles when he took on their precious text, but how about the book that they say is second only to the Bible in Marquez’s native Colombia? Newell sat down along with the film’s producer, Scott Steindorff, to talk about his process. What was the process of getting the rights to the novel?

Steindorff: Well, [Marquez] definitely didn’t want to sell. And over 25 years [he] refused countless, countless offers. When I read the book […] I became obsessed with the book and the characters. It took me about two-and-a-half, three years to get the rights. He rejected me like Fermina rejects Florentino for a long time.

Once it got off the ground how involved was Marquez?

Newell: He sent us a quite voluminous set of notes, and he talked to Scott and said that we were being much too respectful of the novel. He’s a tail-puller—he loves to say the thing that you least expect him to say. But the notes were very good and very helpful, and kind of challenging. What he said was […] ‘Where is the stitch work?’ I puzzled about stitch work and realized that in fact what he meant was that the thing is so heavily embroidered, and quilted, and it’s folded and stitched until everything is connected. That was a very useful note to me, because I said to myself ‘Actually it is possible to do that, but not in a literary way.’

Mr. Newell, this is the second time you’ve taken on a book that people are very fiercely devoted to, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire being the first. How do you deal with their opinions? Do you block it all out, or do you try to strike a balance?

Newell: No, no. You can’t strike a balance. […] Yes, people much more with Potter than with this, challenged the choices. I felt absolutely serene that what I was dealing with was a very elegant classical thriller, and I was going to throw away everything that wasn’t in that, if the studio wanted one film, and the studio wanted one film. I didn’t have a night’s unease. This is different, because this is, to start with, a great, great piece of writing. It must be one of the best novels ever written. It’s also very quirky, so I had to find a way of translating the literary quirks and the quirks that were in the Spanish, and not even in the translation. […] I had to find the spirit of the novel rather than the literal fact of it.

Is there ever any way to get the literal fact of it? Films like A Clockwork Orange, Lolita and Sophie’s Choice, where the writing…

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

Newell: Oh yes. […] What each of those movies does-- Lolita does it, A Clockwork Orange does it—is that what is up there is really clear, and sharp about what it’s trying to do. That’s what I tried to do with this.

One of the things that I find most moving about [this film], apart from it being so humane, is that it’s about real lives lived at the length we all know that real lives are lived. […]The humanity of the story is about long lives, and how people are made desperate by long lives. For instance, my parents’ lives became desperate. Having been sunny and successful, they became desperate toward the end of their lives.

[It’s] a fantastic thing! That at the age of 72, [Fermina] starts a new life. She starts a real, vibrant emotional life. As she starts it she can say ‘I have no idea whether the successful marriage that I am reckoned by the world to have had was love or not. I have no idea whether it was love.’ And here you have this old, old man who says ‘I have fucked 622 women, but I know that this is love.’ There’s such a resounding positive thing about it. The character of Fernando is obsessive, but you were able to transcend insanity over obsession.

Newell: There’s a scene in which he’s sat in an opera house and he’s listening to Puccini and he’s listening to one of the great anthems of heterosexual love. You can see the toll that seeing a depiction of absolute love is taking on him. Inside his head, he’s counting, he’s saying ‘524: schoolteacher, I don’t even remember her fucking name; I don’t remember, I don’t remember.’ That all ends with ‘Routine is like rust; routine is as meaningless and as geological in its time movement as rust is”—that kind of humanizing of a thesis. The book’s full of theses. He says to himself ‘I wonder what would happen if an old, old man came in and declared his love to an old, old woman as if the 50 years hadn’t happened.’ That’s a thesis. But what he then does is to pursue the human truth of the thesis, and that routine is like rust is the human truth. The book is great because of the human truths. The movie in the end, whether I like it or not, ought to be judged by if it brings the human truths to it.

What I found shocking was the scene where the woman drags him into the room and forces herself on him. It seemed strange for those days, when everyone was so chaste—

Newell: You say that they were chaste, but I think that there is a version of behavior that is purely South American where that isn’t quite true. Where, for instance, women are allowed to have appetites in something of the same way that men are.

Steindorff: In South America to this day, women pursue the men. You cannot make an advance on a woman—you have to wait until a woman advances on you, especially in Brazil or Colombia. It is very South American, as Mike says. It’s their culture, and that’s kind of transporting that culture.

Newell: Those Victorian notions of chastity, which we have so strongly in the northern hemisphere, they’re really different in the Southern hemisphere.

Why was it important to film in Colombia, and initially were there any problems in setting that up?

Steindorff: We were initially going to film in Brazil, [then] the vice-president of Colombia called me up and said ‘You must.’ This is next to the Bible in Colombia, their sacred text. The Colombians feel very attached to Marquez and his literature. I was very reluctant to go to Colombia because of the perception of Colombia. He assured me safety, so Mike and I and the production designer went there, and we loved it. […] The perception of Colombia and the reality of Colombia are two different things. We have this perception that it’s Escobar in the 80s, and it’s just not that way. It’s a very safe, beautiful place with warm, generous people.

Newell: I don’t think we could have done it without what we discovered there. […] You have this enormous mixture [of cultures and races] which has made, I don’t quite understand why, a huge, outgoing energy. It’s a very, very energetic place. That’s not saying that they don’t take 2-hour siestas, they do. But their generosity of spirit is fantastic. The whole city turned out for us. I can’t remember how many thousands of people were on the screen.

Steindorff: We have 5,000 extras, and every one of those extras was so committed to just walking down the street. It was fabulous. I would film there, I’m sure you would film there, I would love to film there again. It’s an amazing place.

When you use that many extras do you have to pay them?

Steindorff: Oh yes. Absolutely. And everybody wanted to be involved, because it’s their story.

Newell: We came to realize that another glorious thing about the novel is that it’s also a very accurate portrait of a regional town. Like a French novel might be—a provincial town. You would see the same faces pop up on the street or in the theater or whatever, and to start you would jump and say ‘Oh God, what’s happened?’ because he’s recognizable. But it’s wonderful that he’s recognizable, because of course he would have been recognizable.

Steindorff: It’s like no other place. That’s the nice thing about the book and the movie, is that it portrays a time period within a place that not many people are familiar with. Colombia and this little town that was a mixture of so many different cultures is just so unique and original. It’s so different than Europe and North America.

Did you have to build many sets?

Newell: The big thing was that we built the boats. The boats were a huge thing. Steindorff:. If we would have filmed it in Brazil it would have cost a lot more money, because we would have had to build these locations. We took old buildings—the old opera house was the opera house. Newell: The set in which the girl has her throat cut was simply there in the city, with the trees growing and the same color scheme. All we did was to add birdcages. So you could still find that wonderful 19th-century stuff. It’s there.

Staff Writer at CinemaBlend