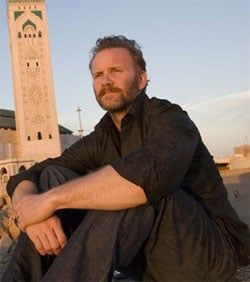

Interview: Morgan Spurlock On Finding Osama

Morgan Spurlock must be the loneliest documentary filmmaker who ever went on a press tour. Without a co-star or partner to share in the drudgery, Spurlock is on his own when it comes to promoting his films. Luckily, he’s the same charming dude we see in the movies, taking on the ills of the world (and the banality of press tours), with jokes. Unfailingly polite, he shakes the hand of every journalist and remembers faces like a champ.

He’s in Los Angeles to talk about Where in the World is Osama Bin Laden,? his latest documentary. A shade more serious than the goofy Supersize Me, this film follows Spurlock as he explores the roots of Osama Bin Laden’s history in several countries around the world. There is a sense that Spurlock has turned his critical eye to problems that affect the world, not just burger-eating Americans. If anyone can deftly navigate the global culture gap, it’s Spurlock. Besides, do you know anyone else that can somberly recount the effects of political unrest on Middle Eastern countries and rattle off the name of every video game console from the early eighties with the same knowledgable authority?

So where is Osama Bin Laden?

He’s up in my hotel room. He’s just hanging out, getting room service. I think he’s still in the mountains of Waziristan or somewhere in that area. When we got to the end of our trip, we were in Peshawar in Pakistan. People were pointing to a direction up in those mountains, which I think, by the time we got to the border, was probably about 50 to 70 miles away, guestimating. I think he’s mobile within that area, personally. Who knows, but I think he’s still there somewhere.

Was the movie shot in chronological order?

Yeah it’s chronologically. We went back and shot some additional interviews later, like the next year after we had our baby. We did some pick ups here and there. But most of it was shot in that timeframe when Alex was about to have the baby.

How proprietary are the Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego people?

CINEMABLEND NEWSLETTER

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

Well Rockapella hasn’t called so I guess it’s all right! They haven’t come out. I think there was somebody else who had a “Where in the World is” before there was a Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego. So for me it was just following a couple different themes.

What would you have done if you had caught him?

We’d have a big party! I’d get, like, a big 25 million dollar Tiger Woods golf check. We talked about it a lot, Danny Marracino (Cinematographer) and myself, about what would happen if we actually did get to speak to him. A lot of people have asked what I would have said or what would I have asked him. I’d have liked to have heard from him how does it end. How does this stop? How can the killing of innocent people end, how can all the hatred end? How can it get to the point that there’s peace and security for everybody? Maybe I’d have gotten a real answer; maybe something real would have come out of that. Or we just might have gotten a whole lot of crazy. Who knows?

Where did the idea for the film come from? Did you just wake up in the morning and decide to make a film about Osama Bin Laden?

Pretty close. It was 2005 when we first started talking about what my next movie would be. We had just finished shooting the first season of 30 Days. Supersize Me did something that none of us anticipated which was play in about 75 countries around the world. It went so beyond our borders and the way it did that made me realize that I wanted my next movie to deal with something that was much more of a global issue and wasn’t just an American issue.

I live in New York City so [terrorism] is constantly out there. I was there on 9/11. This is something that is brought up consistently. Bush had just been elected to his second term and Osama had released a tape. Suddenly the tape was everywhere: on every news channel, every radio station. People were talking about him again. He was completely ubiquitous. All the newscasters were like, “Where is Osama? Why haven’t we found him? Why haven’t we brought this man to justice? Where in the world is Osama Bin Laden?” I said, “That’s a great question, I’d like to know that as well!” So we just started formulating how we would we even make a movie like this, how we would go about finding those answers.

We raised a little bit on money to do some pre-production on the movie from a guy named Adam Dell, who’s the brother of Michael Dell, of Dell computer fame. About two months into that process was when we found out Alex was pregnant. At that point the film took a real shift for me personally. It went away from being just “Where is in the world Osama Bin Laden?” and “What kind of world creates an Osama Bin Laden?” to also “What kind of world am I about to bring a kid into?” That kind of shift made it much more personal for me. Ultimately it made the journey that we went on and the people we went to talk to made the film better.

Is the film in any way financed from Dell Computers?

No, the reality is there’s a guy named Adam Dell who’s in no way connected to Dell Computers, has never worked for Dell Computers. He might own a Dell Computer. That’s the extent of it. He’s a venture capitalist in New York City. He and I met and he said he’d like to make the film and I said that was great. So he helped us raise the first seed bit of money to make pre-production possible.

How concerned were you that at any point during production Osama Bin Laden was found?

It was a concern while we were making the film. If he’s caught, great! That’s an awesome, wonderful thing. You can’t be upset about that. Would it have completely ruined the film that we were making at the time? Possibly. It was thrown a gigantic wrench in the plans. We would have figured it out somehow.

Even if they would of found him I think a lot of the things people talk about over the course of the movie would have remained the same. What you start to see is as much as Osama Bin Laden isn’t in Egypt or Morocco or Saudi Arabia or the Palestinian territories or Afghanistan or Pakistan, he is in all of those places. His ideology, the way that he thinks, has infiltrated these countries. Especially people who are in that minority that get all that air time here in the United States. I think what the film does a really good job of doing is starting to give a voice to that silent majority, the people that we don’t give enough air time to in America. I think that film does a great job of getting out of those two minute sound bites we hear on the news and painting a much different portrait for what life is like in the Middle East for many of these people on a daily basis.

Part of the film was seeing how the attitude towards America and Americans has changed. How much of an eye opener was that for you or did you go in understanding that some people don’t like us as much as they used to?

See, I think they don’t like America’s foreign policy as much as they used to. I think people still have a tremendous amount of hope in what America means and America is. America is a dream and an ideology and a hope that things can always be better. That’s how a lot of people see the United States still. A lot of that has been shattered over the course of, for some people, 5 years, for some people the last 10 or 15 years. As you heard consistently, it was “We don’t hate the American people but we hate what’s happened to the American government and what has transpired.”

I think that we’re still taught that people hate us. They hate us. Them. Those People.Those people are a monolithic thing. That’s just not the case. We like things to be very simple and in a little package and it’s much more broad than that.

Over the course of the film, even when I go on my travels, you see that, from the different places we go. There’s a much more diverse brand of Islam in these countries in how it’s practiced. I personally thought that I was going to be met with a lot more hostility and resentment and that people weren’t going to want to talk to me because I was an American. It was completely the opposite. People really were eager to sit down and share their feeling and share their outlooks and share their opinions. These are people who don’t get to speak in a lot of these countries. These people live in countries where if you speak out, you’ll go to jail. That’s terrible. So I think for them to be able to sit down with somebody who they see as part of the Western media and be able to express their thoughts, knowing that it could potentially reach people in America is very brave.

Did you ever feel threatened during production, as if you were in real danger? And also, in the film you stay with the military in Afghanistan. It looked like they were sort of looking out for you. How did that go?

The embed that we did with them was fantastic. Those guys are heroes for what they do. These guys put their lives on the line every single day to go out there and do their job, to help make Afghanistan a better place, a safer place. But at the same time the reality is that those guys are targets. The whole trip we went on, the most fear I ever felt was when we were with then because every day there’s potential for danger. Every day there’s the possibility that when you go out something really awful could happen. We’re with them when there’s a Taliban ambush on the governor’s convoy and one of the Taliban gets killed. There was another day when we were in a convoy with them and the convoy got diverted because they discovered an IED less than kilometer in front of them. They diverted us back to the base and the explosive experts went over there and detonated this IED. Things could vastly be different every day and that’s the frightening reality of being one of those guys.

Your relationship with Alex has been pretty…

Tumultous?

Considering the danger of both your films and the segments of 30 Days you’ve done, so how short of leash are you going to be on for your next film?

It’s about this long! She’s already told me my next film should be about how to make your wife really happy. I don’t know if I know how to make a movie like that. I’m trying to make it up to her every day.

A certain point of your work is doing something a little bit dangerous, whether it’s to your own health or getting out there.

The next time I’m going to try not to do that. I’m going to try to not make it so dangerous for me.

One of the cool things about your films is that you’re really the same guy who’s sitting here now and you’re so empathetic, you could be my neighbor.

I wear a cardigan usually and put on tennis shoes when I come in.

In that spirit, what was it like for you when you went to Israel and were pushed by Orthodox Jews?

It was surprising. We all couldn’t believe what happened. I’ll tell you a couple of things about that scene. Our producer had gone and interviewed people in the Orthodox neighborhood before and said it was fine, don’t worry about it. So we go in there and we’re shooting with a big giant HD Hi-Def camera, which I’m sure concerned them. We’re asking political questions, which I’m sure they didn’t like, and a couple of people started to get upset. It wasn’t a lot. It was probably like 5 or 6 people out of the 100’s you see getting upset. For me the greatest thing in that scene is the guy who makes it a point to come up to me and say, “What you see here, the majority of us don’t think like them.” He was really concerned about perception: How am I going to be perceived because of what these people are doing? I think there’s a fantastic parallel to that with all the people we meet over the course of the film. Don’t group us into this group of people who do awful things. That’s not who we are, that’s not what we believe. I found that to be really beautiful.

With Supersize me, like this film you started with this “fun” premise but there was some real change after that movie, and not just with McDonald’s. What are you hoping will change as a result of this film?

It wasn’t like we went into Supersize Me saying that we were going to make a film that was going to change everything. It’s really not the goal when I go in to make a film. The biggest thing is to make a good movie, to make something that I’m passionate about, that speaks to me as a filmmaker. The greatest thing I thinkSupersize Me did was empower people. It empowered individuals. As much as it made McDonald’s or other corporations look at how they do business, it made individuals look at the choices they make.

Maybe this film can serve as a primer to a larger discussion between people who’ve sort of tuned out. We live in a country where a lot of us have become complacent and apathetic and we’ve shut down. There’s so much bad news that we’ve lost sight of optimism and hope. So maybe it can serve as a bridge.

I was surprised that out of every country you went, Israel is where you got the most resistance. Where you surprised by this?

I think there were places where we felt resistance but there weren’t places where we were physically confronted. There were places where crowd gathered and you’d start to feel a little odd. Like, you’re in the middle of Pakistan and a crowd starts to gather while you’re shooting and a guy pulls out his cell phone. There’s places where things could go desperately bad but Israel was the place where a guy physically pushed me as I was trying to leave. We were completely surprised that it happened.

Where you ever on the radar for homeland security? Have you thought about that?

Maybe this room’s bugged right now! Some FBI folks actually came by our office. We had sent some pictures over to Morocco when we were going to do some pick up shooting. We had photographs of Osama Bin Laden in different places. We had him in Casablanca dressed up as Humphrey Bogart, wearing a trench coat and fedora. So these pictures got stopped in customs and when our producer went to pick them up, he got taken to jail and they were asking him about the photos. And we were calling their government to get him released. So the FBI comes to our office and asks about the photos. “Why do you have those?” “We’re making a movie.” “What’s the film about?” “It’s about Osama Bin Laden.” “Why are you making a movie about Osama Bin Laden?” “I’m looking for Osama Bin Laden.” “Why are you looking for Osama Bin Laden?” “Why aren’t you looking for Osama Bin Laden?” “Mr. Spurlock, have a good day.” End of conversation.

Your name has been connected to an adaptation of the book The Republican War on Science? Any news on that project

We bought that book a couple years ago. We optioned the rights to that in 2004 right after Supersize Me came out. We’ve given up the option since then. That would’ve been a great film to make 3 or 4 years ago but it’s not as relevant now.

It would hard not to be political when dealing with source material like that.

With a subject like that it’s not a straight Republican issue. It’s a very political issue in how the government views science and what parameters researchers have to work in when trying to get funding from the government. There’s a tremendous amount of give and take on both sides of the aisle. There were a lot of things we were going to talk about but we’re not going to make it now, so it doesn’t really matter.

Is it easier to stay apolitical in your films?

I think it’s easier to stay more political. I think if you watch this film you’re hard pressed to find my politics in it. I think you’re hard pressed to find my politics in a lot of the stuff we do. Especially the shows that I’m in, the films that I make, I want people to make up their own mind. I’ll tell you what I’m feeling and what I’m thinking when I’m in this moment of being there, immersed in this journey that 99% of us will never get to go on, meeting people that 99% of us will never get to speak to, being in a situation that 99% of us will never actually experience. So what I want to do is try to be honest with you about what I’m feeling and what I’m experiencing while this is going on so that you can’t feel it. As I’m learning you’re learning. As I’m feeling you’re feeling. For me there’s something very exciting about that. I just try to be as honest as possible in that moment and not browbeat you with personal opinions. I don’t think that’s the right way to reach as broad an audience as possible.

What was the it like shooting is Saudi Arabia?

Shooting in Saudi Arabia was incredible because it’s a country where there’s a façade. On one side is an incredibly conservative country that at the same time is fighting against religious conservatism, westernization, modernization, Americanization. There’s mall everywhere, there’s fast food restaurants everywhere. The street where the kids cruise on Friday nights is book ended on each end by a McDonald’s and a Chilli’s. That’s the U-turn where they turn up a go back down the street. There are so many things we couldn’t put in the film about Saudi Arabia that I talk about in the book. There’s this huge underground party scene, underground drug scene, underground gay scene. All this stuff is there; it’s just behind closed doors. Nothing is talked about. It was a fascinating place to see.

Do you feel you’ve taken over Michael Moore’s role as the every man documentary hero?

I don’t know. I’m just trying to make movies that hopefully people like and that I like.

There are two schools of thought in documentary filmmaking, one being that the documentary maker should be a character. You’ve made the decision to be part of your films. What went into that?

It became very evident to me when we were making 30 Days and we did the episode where my wife and I lived on minimum wage. For me there’s something really exciting about giving you insight into a world where I take you with me. It’s not like you’re just watching other people live. Hopefully you and I start to build a relationship with each other so when I go on this trip, it’s like someone you know is going. And I’m telling you the story. Hopefully it will be more relatable to you than if you were just watching it in an omniscient documentary. Hopefully it will become something more personal, more emotional by doing that. That’s the goal for me. That’s what I’ve tried to do.

You use a lot of video game animation in the film. Were you trying to reach a younger generation of movie goers?

It was trying to reach me! That’s my generation. I’m a child of the video game generation. I grew up with Pong in my house and then an Atari 2600. Then my friend got an Intellevision and then I got a ColecoVision vision. Then another friend of mine got an Atari 5200. Then I went to school and got a Nintendo and another friend of mine got a Sega. Then I got a PlayStation and then I got a PlayStation 2 and a PlayStation 3. Just last week I got a PSP before I went on the road for my press tour.

I think video games are fantastic and they do touch people from my generation which is just under 40 and all the way down to kids who are 10 and some even younger. There was a part of that for me that wanted to push the narrative along in a way that would be interesting and relatable to a lot of us. That demographic of like 10-40 is the video game sweet spot. That’s a lot of people.

So when does the game come out?

Weinstein asked the same question. They were like, “Hey, when can we make this game?”

What was the most memorable moment of the whole film for you? There are so many things you can’t predict when you make a documentary and for me that’s the best thing. I got some incredible advice before we made Supersize Me. Because I had never made a feature length documentary I was calling around and asking people how to do and what advice they had. And a friend of mine said, “If the movie you end up with is the exact same movie you envisioned when you started then you didn’t listen to anybody along the way.” That’s so true. When you get out in the field it becomes organic, it becomes its own animal.

Here we were driving on our way back to Tora Bora when we saw the Bedouins off on the side of the road and we just stopped the car. We went out in the middle of Afghanistan and having tea with Bedouins in the desert, just talking about what their life is like. There are so many little things that were just incredible.

Do you keep in touch with anybody you met on this film?

Yeah there are people we still email back and forth with. A lot of the producers that we worked with in these countries we still email with. A couple people that we interviewed in Saudi Arabia or Pakistan we’ve stayed in touch with. It’s hard to stay in touch with people in Afghanistan with the exception of the troops. We’ve emailed back and forth with those guys. We tried to stay in touch with a couple of guys in Egypt to see how they are because that’s a place where speaking out could potentially be dangerous for them.

What about showing the film in those countries?

In Saudi Arabia, where there are no movie theaters and no movies, there are so many movies. The movie premieres here this Friday. My prediction is that by Saturday it’ll be everywhere in Saudi Arabia, on the black market, on the web. The bootleg will be out. It’ll be out fast so I’m anxious to start getting feedback.

How do people react when you go into McDonald’s now?

I don’t go into McDonald’s now so they don’t react. People might see me walk past a McDonald’s but I never go in.

It takes so long to shoot a documentary, do you have to worry about career momentum between projects?

We were fortunate that over the course of making this film we got to do 2 seasons of 30 Days and we were finishing the 3rd season when we were in post on the movie. It’s not like I’ve been sitting down doing nothing. We produced the film What Would Jesus Buy that came out last Christmas, it’s coming out on DVD. I’ve been trying to do what I can to do some different things outside of making films but I find films to be so gratifying.

Most Popular