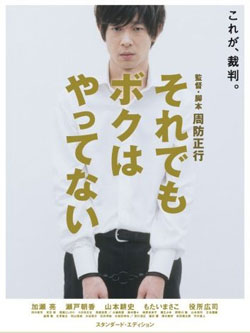

NYFF: I Just Didn't Do It

Though it’s set in a distinctly modern-day Japan, I Just Didn’t Do It is a deeply old-fashioned film. It’s the kind of social problem movie that would have starred Henry Fonda back in the day, an earnest legal drama with the simple goal of examining the problems of the criminal justice system. Japanese courts have a 99.9% conviction rate for all cases, an astonishing statistic that indicates a serious lapse in the “innocent until proven guilty” concept. Director Masayuki Suo uses a relatable, falsely accused hero to explore this complicated system, telling a story that seems to be all-too-common.

On his way to a job interview, 26-year old Teppei Kaneko shoves his way onto a packed commuter train, behind a 15-year old schoolgirl. Preoccupied with freeing his jacket from between the doors he barely notices the girl until she stops him on the platform and accuses him of groping her. Teppei is immediately whisked away to a holding cell, repeatedly questioned by detectives, and ignored or laughed at when insisting on his innocence. Teppei is held in jail until trial while his best friend (Kohiji Yamamoto) and mother (Masako Motai) hire lawyers to defend him. Teppei is repeatedly told that a guilty plea will result in a lesser sentence, but he holds steadfast to his innocence.

The story plays out in a very, very straightforward manner with one odd exception. When Teppei tells his story to the detectives, we see his flashback—his jacket is caught in the door, he accidentally nudges the woman next to him, he never sees the schoolgirl until she apprehends him on the platform. When the detectives give their version, however, we also see a flashback, in which Teppei gropes the girl after all. Flashbacks have enormous power, especially in a film with differing versions of the same story--Rashomonbeing the classic example—and these conflicting flashbacks set side by side seem intended to cast audience doubt on Teppei’s story. From that point on, though, the film remains on Teppei’s side, and never gives any indication that he’s telling anything but the full truth.

And from that point on, the film becomes a bloodless, plodding legal drama where there are no criminals, and therefore nobody remotely interesting to watch. The audience gets a no-holds barred look into every single step of the Japanese trial system, which Suo indicated in the press conference (see below) was his intention; as anyone who’s ever seen Schoolhouse Rocks knows, though, dramatizing the ins and outs of the government is a tricky business, and so rarely interesting. Though it’s enough to make anyone in Japan nervous, knowing how easily it is to be wrongly accused, the stakes here simply aren’t that high; a guilty plea and an innocent plea both yield about 3 months in prison, which is even less than Martha Stewart faced. It’s hard to wring your hand over a verdict when, 3 months later, everything will be back to normal.

Suo has a noble goal in making his film, but unlike other rabble-rousing filmmakers (see Brian DePalma’s press conference about Redacted, coming to this site shortly) Suo doesn’t translate the sense of outrage to the screen. I Just Didn’t Do It is an episode of Law & Order without a crime, or bad guys, and it’s over two hours long. I could have read the Wikipedia entry on Japan’s legal system in less time.

Masayuki Suo sat down for a press conference following the screening of his film, where he shed more light on his goals to, well, shed light on the Japanese criminal trial system.

It's been 10 years since your previous film, Shall We Dance? Why did you wait so long to make another film, and how did you come to make this one?

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

Masayuki Suo: Actually during these 10 years I had three projects which I started research on, but none of them unfortunately came into existence. This was the fourth project I was workig on during those 10 years. It has been six and a half years since I started working on [this project], but this was the one I felt I absolutely had to do. It all started with one newspaper article. A businessman was arrested for groping on a train, and in the first trial he was found guilty and was convicted. He appealed, and the article was about the high court overturning the conviction from the lower court. It all started there. To my surprise, many of the people accused of groping actually plea not guilty, but somehow they end up getting convicted. Of course they're convicted on the basis of victim's testimony and testimony alone. No physical evidence is usually presented. I was very surprised by this fact, and I felt very strongly about this. Of course, many of the false accusations that happen in court, it's not just groping cases. Just the fact that there is 99.9% percent conviction rate--that alone means the judges are presuming the accused are guilty. That's what’s wrong with the Japanese trial system.

Some say the social problem film is rare in Japan—is that true? If so, do you feel you're part of a new trend?

Actually I believe it is not true. There are many films that deal with these social problems; however many of them are not commercial successes. Up to the 70s the Japanese film industry made lots and lots of films as social critique. But after that they have not been able to achieve the commercial success. This film obviously was going to be a social drama. In my mind I've always been a director of social drama.

The dialogue was very accurate. Was anything taken from transcripts of actual trials?

I went about 200 times to listen to the actual trials. Much of the dialogue is actually taken from my notes. I really wanted to convey the current state of Japanese criminal trial. If someone is commending me for good dialogue, I was really lucky to have a great translator.

How do the gender relationships in the film and the female characters—the victim, the mother, the girlfriend—reflect on Japanese society, which is traditionally male-dominated?

At one point I was afraid the female audience might not like making a film about a groping cause, one that involves a false accusation. The accused who are falsely accused also have their women around them. The accused [in the film], he was a relationship with his girlfriend, he has a mother. There are females around the victim and the accused as well. Once the trial starts everyone gets involved. This is a point that I wanted to make, that once the trial starts it involves everyone. Not a single so-called criminal is actually involved in this case. Of course I did feel that I had to incorporate the women's point of view, that's why the female lawyer character is there.

This film is really not about gender. It's really about trial and how it's conducted. I could have dealt with a murder case or robbery case, and that could have been easy. I chose a groping case just because this so-called crime could happen to anybody at any moment. Of course in Japan its' a very, very common crime, and it happens every day, and there are many, many victims who actually don't bother to go to the police. Any ordinary Japanese man could be mistaken as a perpetrator, or any female, or anyone could become a victim of this crime. I wanted to stress that this really could happen to anybody, and that's how I wanted the audience to relate to this film.

There’s a big contrast between scenes with the police, which are tightly framed, and then later there's lots of camera movement. Can you talk about that choice?

I chose this style specifically for this subject matter. I usually like the fixed frame, and I usually don't like to move the camera. I tried to stay fixed as much as possible in the courtroom, and if the camera is moving I wanted to make it a very, very smooth movement. Once the camera is outside of the court I tried to use handheld.

How did you cast Ryo Kase as the lead?

In many cases the defendant in a groping case is a businessman, and the businessman obviously has a lot to lose. In the film I wanted the audience to pay attention to the trial and proceedings, so I chose a young man who has not much to lose. Ryo Kase walked in [a casting session] and I suddenly knew the main character of the film just walked into the room. I usually don't do casting based on my instinct, but in this particular case it was so clear to me he was exactly what I had in mind. He's acting in the film, but for me, the main character of the film is Ryo Kase almost. As many of you know, Ryo Kase was in Letters From Iwo Jima, and I believe Clint Eastwood and I have the same taste.

Staff Writer at CinemaBlend