Mike Tyson is 42 years old, a fact that's hard to believe both looking at him and regarding his impact on popular culture. The heavyweight fighter is known as much for his intense ring presence and unprecedented series of knockouts as his effeminate voice and marital troubles; he was one of the highest paid boxers in history, but may be best remembered for biting off an opponent's ear.

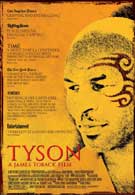

To make his documentary Tyson, James Toback accepts all of these facts and any of the others that Tyson spouts. A deliberately, consciously one-sided film, Tyson is more like a stream-of-consciousness journey through Tyson's mind, told entirely in his voice over the series of several sessions with Toback, a friend, behind the camera. Starting from a rough childhood in Brooklyn, where Tyson describes himself both as the smallest and the biggest kid in the neighborhood, he tells his own rags-to-riches story, stopping to lionize his trainer Cus D'Amato, who became Tyson's legal guardian when he was 16.

D'Amato died early in Tyson's career, in 1985, and the mercurial brawler we know emerged from there. Tyson speaks with genuine emotion about his series of early career wins, describing in detail each jab and feint he used to take down opponents, and talking of the confidence that emerged in him as he got closer to the ring. But as the story gets shadier, culminating in his 1991 rape conviction, Tyson's memory grows suspiciously less sharp. He insists that, while he may have taken advantage of other women in his life, he never raped Miss Black Rhode Island Desiree Washington, whose testimony sent him to jail for three years. And speaking over footage of an emotional interview he and then-wife Robin Givens gave to Barbara Walters, he insists that Givens was lying about his emotional abuse.

Clearly Toback is making a choice by taking these statements at face value, and never bothering to get the other side of the story. But as the self-justifications pile up, Tyson's open honesty comes to feel like another way of boosting his own image. He's willing to talk in detail about the famous ear-biting Evander Holyfield fight, but claims that he blacked out in every moment in the ring, not even trying to provide justification for what he did. Paired with footage from the fight, which show Tyson to be disoriented and full of blind rage, that could very well be the explanation. But with no sense that Toback is pressing Tyson behind the camera, it's easy to see this as more of a puff piece propping up Tyson's sense of importance rather than any work of documentary filmmaking.

Toback's technique, including split-screens of Tyson's face and layering his voice over itself, completes the effect of full immersion within Tyson's brain. Toback himself starts to feel like an extension of Tyson, meaning that repeated shots of Tyson staring contemplatively at the ocean seem as self-aggrandizing as if Tyson had shot them himself. We can all be glad that Toback has ventured into the heart of darkness that is Tyson, a man clearly still tormented by the past. But it's hard not to be disappointed by the lack of conclusions Toback came back with.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

Staff Writer at CinemaBlend