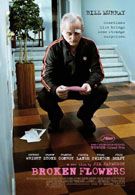

I heard someone the other day refer to Broken Flowers as the third film in Bill Murray's loneliness trilogy, and that really seems true. His late career projects seem rooted in longing and regret, brief snapshots of men looking back on the most productive parts of their lives and wishing they'd found something more substantial in them. Lost in Translation, The Life Aquatic, and Broken Flowers all utilize Bill's talent for deadpan stoicism to create characters who have so cut themselves off from the world that somewhere along the way they've lost track of what it was they were living for in the first place, if indeed they ever knew.

Of those three films, Broken Flowers is the least obviously engaging. The movie is written and directed by Jim Jarmusch, a longtime critical darling of the indie circuit who seems generally disinterested in making anything accessible enough for mainstream audiences to embrace. Broken Flowers is without a doubt his most commercially viable project, though with Jarmusch that probably isn't saying much.

The movie opens simply, by contrasting the large, stylish home of Don Johnston (Bill Murray) with that of his neighbor and best friend Winston (Jeffrey Wright). The exterior of Winston's home is a hive of life and activity. Kids run through the yard screaming and playing, toys lay scattered in the grass. Don's house is clean, and quiet. Don sits on his leather couch, in front of his big screen TV and stares blankly, only showing passing interest when his girlfriend packs her bags and announces she's leaving, probably for good. He's an aging Don Juan, a confirmed bachelor (not of the Rock Hudson variety) and now after an innumerable amount of women he's dead to the process of dumping and being dumped. It's soon thereafter that Don receives a letter, a pink letter with no return address and no signature. The letter tells him he has a son, and that his son may be looking for him. Don wants nothing to do with it, but his friend Winston fancies himself an amateur Sherlock Holmes, or as Don glibly suggests, Dolemite.

Prodded (at least on the surface) by Winston's incessant curiosity, Don embarks on a journey to visit his old girlfriends with disinterested resignation. With help from Winston he'll visit each under the awkward guise of "just checking up" and look for clues about who it was that sent the letter. Does Don have a son? Does he want a son? Does it even matter? Broken Flowers is a lot better at posing questions than it is at providing answers. By the time it's over, you get the sense that the answers don't make a difference. This is a film more about Don's emotional journey than it is about uncovering the mystery that Winston believes surrounds him.

Filled to the brim with long, pregnant pauses and bouts of languishing silence, an inordinate amount of celluloid is spent zoomed in on Murray's craggy face, just watching him think. This is a film driven not by dialogue or happenstance, but on the turmoil swirling in Bill Murray's sad, aging eyes. With each woman he visits, Don sees something different, and we see something different in him. Is he thinking of missed opportunities? Is he saddened by what she's become? What did these women ever see in him in the first place? Broken Flowers is enigmatic, quiet, and introspective. It's not particularly beautiful, nor is this story instantly striking, but Murray's quiet sadness is so complex that it heats what might otherwise be a slow, boring film.

Broken Flowers won the top prize this year at Cannes and perhaps deservedly so. But, like everything Jarmusch does this isn't a movie that reaches out to the audience. It's storytelling in muted tones, characters portrayed with such remote realism that it almost feels like an arm's length documentary. Answers are nowhere to be found in Jarmusch's determined detachment, but there's powerful drama in Don Johnston's journey. Bill Murray's empathetic performance makes it worth following.

Most Popular