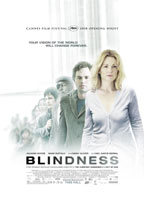

For his second English-language film, Fernando Meirelles, one of the most visually expressive filmmakers working today, has chosen to make a film about people who have gone blind. It would be a sick joke if Meirelles didn't take it so seriously, translating his visual flair into a story that allows the audience a sight that none of the characters, save one, can have. Blindness, an adaptation of Jose Saramago's allegorical novel, is a brutal slog in some parts, but it also powerfully lifts the veil on human decency, revealing the worms, dirt and brutality that lurk underneath.

The movie starts as some of the best end-of-the-world stories do, with unrelated residents of an unnamed city suddenly, inexplicably going blind. Chief among them is The Doctor (Mark Ruffalo), who treats the first man struck with the blindness (Yusuke Iseya) and goes blind himself the next day. Though the Doctor's Wife (Julianne Moore) is not blind herself, she goes with her husband to a quarantine facility, where they are joined by increasingly more victims of what's being called "The White Sickness." We see various news reports and government summits trying to solve the crisis, but soon we are trapped within the crumbling mental facility that grows ever more crowded with the blind.

The only sighted person in the building, the Doctor's Wife is the only one to bear witness of the fetid, miserable cell, and she and her husband do their best to maintain order and a sense of democracy. But as food shipments grow scarcer, and the outside world seemingly abandons them, a man who dubs himself the King of Ward Three (Gael Garcia Bernal) stages a coup, hoarding food and demanding bribes from the other wards. At first it's jewelry, but soon women from each ward are being recruited as collateral.

Filming so much of his movie inside cramped, disgusting quarters, Meirelles makes the most of his camera, washing out the film's colors to emulate the "white" blindness, using quick cuts and all kinds of crazy camera angles both to convey the sense of growing madness in the hospital and emphasize the audience's gift of sight. There's an issue of voyeurism here, in what the audience can see that the characters cannot, but Meirelles unfortunately ignores it for the large part. Had he indicted the audience as voyeur, as Hitchcock and so many horror directors have done, he could have truly distinguished his film from the novel; instead the literary roots stick to the film a little too closely, particularly in the conceit of giving no names to its characters.

Bear with me while I get a little theoretical here. Allegories work in novels, and have for centuries, because characters that exist only in your mind can stand for anything-- pigs can stand for Russian communists, the Salem Witch Trials can stand for McCarthyism, etc. But film is exceedingly literal, with each character represented by a single actor, so that the Doctor's Wife may be intended as a larger symbol of humanity, but is always also Julianne Moore. In that way the scale of Blindness becomes diminished, a story about one nightmare in one quarantine ward, rather than the sweeping metaphor the novel likely is.

The stellar performances (particularly from Moore, Ruffalo and Bernal), impeccable production design and stirring, though occasionally flashy, cinematography make Blindness worth the suffering it inflicts on its audiences. It doesn't quite reach the allegorical, accusatory heights it seems to aim for, but it offers a chance for stark reflection, and invites the audience to make the leap from the fictional blindness to whatever real-life disaster is happening today. A sharp view of humanity with a glimmer of hope, Blindness is a movie for our times-- flawed, brutal, with key moments of brilliance.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

Staff Writer at CinemaBlend