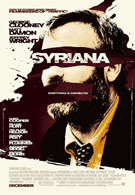

Harry Cohn, the founder of Columbia Pictures, bragged about rating films by the seat of his pants. Literally. If his butt would start wiggling, he knew he had a dud on his hands. Now, I’m no Harry Cohn, but fifteen minutes into Syriana, my butt was doing the cha-cha-cha. Having seen the trailer, I expected the film to be an exciting political thriller. But no. Despite its complex story and varied international settings, Syriana plods along like a tired old horse with leaden shoes.

It’s quite clear that the film’s creators had lofty ambitions. By the date of its limited release, Syriana was already being flacked as Oscar material. Much of the advance buzz has dwelt upon the fact that George Clooney put on 35 lbs for his role as a senior CIA operative. Watching the movie, I began to suspect that he’d gained the weight during filming by eating too much falafel and that the implied self-sacrifice for art's sake was an afterthought. In any event, had he done the opposite and starved himself to the brink of death during the Ramadan fast, it wouldn’t have made much difference. His competent performance as the only character with any depth isn’t nearly enough to salvage the film from the ash heap of the might-have-beens.

Syriana deals with the morally murky interactions between big business and government. Here, the petroleum and natural gas industries are the focus. Clooney plays Bob Barnes, a veteran CIA agent who, over the years, has killed for the good of the old U.S.A., but is still basically the kind of solid, stand-up guy that Clooney portrays so well. Barnes is sent to Lebanon to kill a couple of arms dealers. Things go awry and a Stinger surface-to-air missile ends up in the wrong hands. He is then assigned to kill Prince Nasir (Alexander Siddig), a benevolent, principled, idealistic ruler of a Persian Gulf nation who puts the interests of his subjects first. Nasir has canceled a longstanding contract with a giant Texas oil company, Connex, and instead has made a new arrangement with China. Meanwhile, a smaller American company, Killen, has acquired drilling rights in Kazakhstan, making it an appetizing morsel for Connex to swallow up in a merger. The proposed marriage is being scrutinized by the Justice Department, and a meek-appearing but strong-backboned D.C. lawyer, Bennett Holiday (Jeffrey Wright), is retained by Connex to find out whether there’s anything suspect about the merger before the Justice Department has a chance to.

Geneva-based energy analyst Bryan Woodman (Matt Damon), starts working for the Prince. Woodman and his wife, played by Amanda Peet, endure a terrible tragedy that threatens their already-rocky marriage. This subplot, in view of the gut-wrenching event that sets Woodman’s relationship with the Prince in motion, is given particularly short shrift, to the further detriment of the story. Yet another plot thread involves two Pakistani oil workers laid off as a result of the loss of the Connex contract. One of them is seduced by a radical cleric, with deadly consequences.

The overall acting performances are strong, but the film has little new to say. So governments and big business play by their own rules. Big deal. Haven’t we already figured that out, between the deceptions foisted upon us by our current administration and the excesses of Enron, WorldCom, and their ilk? The film was mercifully cut by 30 minutes, but still goes over two hours and feels even longer than that. Attempts to give Syriana an air of documentary authenticity, with long stretches of dialogue in Arabic and Farsi, are of little interest or avail. There’s a torture scene that will have the squeamish wishing they were watching the film on an airplane with a barf bag right there.

“Everything is connected” is the movie’s mantra, so I guess we’re supposed to believe that there’s some kind of terrorist butterfly effect happening. Each time you pump that overpriced gas into your tank, across the world a screaming fanatic is blowing himself and anybody in his vicinity into subatomic particles.

The film has a condescending flavor, with an, “I’m O.K., and if you don’t get me, you’re a dumbass” attitude. Fact of the matter is that the film is confusing, and there’s little excuse for that. It’s not an art movie, after all, but a very ordinary genre flick. By the end I was hoping that Borat, Sacha Baron Cohen’s Kazakh reporter from “Da Ali G. Show”, would materialize, bellowing his pidgin-Polish signature greeting, “Yagshemash!”, and explain what was going on. Writer-director Stephen Gaghan, who wrote the screenplay for the far superior Traffic, has been quoted as saying about Syriana, “The hope was that by not wrapping everything up, the film will get under your skin in a different way and stay with you longer.” Sorry, Gaghan old chap, but your movie got under my skin the same old way, and evaporated like a light sweat, the instant I left the theater.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News