Wrath Of The Titans Director Jonathan Liebesman Discusses Doing 3D And CG Right

It ain’t easy getting work in this industry, especially a film like Wrath of the Titans, but boy did director Jonathan Liebesman take on, well, a monster. While Clash of the Titans went on to make a killing at the box office, $493.2 million worldwide, many moviegoers weren’t particularly happy with the experience. In a way, not only is Liebesman responsible for making his own movie good, but also for making up for the last one a bit.

Sam Worthington is back as Perseus, who is now a father. With the gods’ power waning, Zeus (Liam Neeson), Hades (Ralph Fiennes) and Poseidon (Danny Huston) are unable to maintain control of the Titans and, led by their once banished father Kronos, they threaten humanity yet again. Perseus has no choice, but to leave his son and quaint life as a fisherman behind to go head to head with some of the most vicious monsters of the underworld.

Kronos, Chimeras, Cyclopes, explosions an ever-changing labyrinth, some of the most prominent actors in the business, an extra dimension and more – forget the franchise’s past; Liebesman had his hands full regardless. Now, in honor of Wrath of the Titans’ March 30th release, Liebesman took the time to sit down and run through the entire process from the preparation needed to do 3D right to the steps to making the real world elements blend with those digitally created and much more. Check it all out in the interview below.

How does something like this fall into your hands?

Jonathan Liebesman: It doesn’t really fall into your hands. [Laughs] In my case it took like ten years now that I think about it. You work on movies and then I did this film Battle: Los Angeles where I had to fight for the job really hard and fortunately on this one they approached me. And obviously the cast is incredibly and the subject matter is fun and the budgets they give you are amazing, so it’s kind of a no-brainer as an opportunity.

So after you get this great opportunity is there ever a moment where you go, wow, now how am I going to pull it off?

There’s always that. Even when you’re doing a student film, you go like, ‘Fuck, how are we gonna do this?’ There’s the exact same anxieties. It’s no different. It’s just as big a part of your life.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

And how about the fact that there’s another film in this franchise and that that film made a ton of money, but some people didn’t necessarily think it was worth theirs?

Well, it’s hard because you hope that they’ll pay for this one and come back and see it. Everyone acknowledges and wants to make something better and, you know, they’re such talented people whether it’s the cast, the crew, everybody. Look, if you’re gonna go into something completely intimated, don’t do it. I think what money gets made is out of my hands. There’s The Hunger Games this week, which no one expected, which is destroying the universe. So you can’t expect these things; you just try and make the best movie you can make.

How about the 3D because a big reason people weren’t thrilled with the first is you pay so much money for the ticket and then the 3D wasn’t that great?

The thing is, that was an easy solve because the 3D on the last movie was shit because they finished the film and decided to convert it and gave it six weeks to be converted, which is 1,800 shots in six weeks, no shots were even planned to be 3D shots, no sequences were planned to be 3D sequences. You can’t win. We knew we were gonna be a 3D film so you plan everything for 3D, you have a stereographer on set everyday, you start your post conversion a year in advance instead of six weeks in advanced and you create moments that suit 3D. It was a different ballgame. Those poor guys were set up to fail. This was a completely different situation. We had a great team from Harry Potter that did great conversions, so we always had our best foot forward with the 3D on this movie.

Now how does that affect your preparation process in terms of storyboarding or whatever it is you do to get ready to shoot?

You think in terms of what can we bring into negative space or what happens often, I had to learn this, negative space means when something is in the audience and so if you bring Perseus and Pegasus into negative space, there’s an effect where they feel miniaturized, but we actually used that to the advantage, say, in scenes with Kronos, because you really feel like Perseus is tiny and Kronos is massive with the 3D. So the 3D really enhances things. Also I believe the best looking 3D is when you bring little things into the audience, like embers or water droplets or stuff like that, so we added a lot of that or showed a lot of that stuff so you could bring it into the audience.

Funny you say that, at one point there was this one ember that felt like it was coming right towards my eye and I actually winced!

I think that stuff works the best. For 3D to be good you can’t cut things off in the frame and so embers are tiny, so they’re not gonna be framed out and the longer something stays in frame for 3D, the more effective it is, so those are always best - bubbles, embers, dust.

So going from the highly technical to black and white, when you get a script like this what happens if you come across something that isn’t working? Do you have the ability to make adjustments?

Well, you ask a lot of people, you sit down with the writers. It’s always a discussion on a movie like this. Unless you’re Chris Nolan, it’s always gonna be a discussion of can we make this better, this is what I’m going for, it’s about fathers and sons, maybe we can push that more in this scene. That’s studio filmmaking. The benefit of a studio filmmaking is you get an incredible distribution and you get an incredible budget. The downfall is obviously you are responsible to the people giving you the money.

Speaking of the father son stuff, the added drama here kind of creeps into the action, too, specifically in terms of the use of close-up shots in the battle sequences.

I think for me the most effective action that I’ve seen is movies like Private Ryan or the Bourne movies where it is subjective and the action is character driven. In say Bourne, it’s like Matt Damon’s stress as he goes through situations or Private Ryan, the fear of the soldiers or even in M:I 4 it was really great the way they used Tom Cruise and he’s always under pressure in every scene and it’s about him so you don’t even think you’re in an action scene. You just know you’re in a scene where he has to win. So those are my favorite action scenes and we were just trying to, I guess imitate that kind of stuff.

How do you do that and also make sure that the audience understands the geography of a battle?

It’s interesting. I think it’s more important to know emotionally what the character wants. I asked that exact question to Paul Greengrass after I saw Bourne Ultimatum because I was like, ‘Paul, I don’t know how you managed to let me know where the hell I was because it was just so quick and fast.’ I said, ‘How do you know when to cut wide, when do you go in close?’ He didn’t really answer me, but what I realized was you just know what the character wants and you go with it and you feel like you know the geography. Of course you have a wide shot that shows you a vibe of the location, but it’s more about if emotionally you’re with the character, the geography matters a lot less.

Can you tell me about your locations? Obviously there’s a ton of green screen and CGI, but imagine a lot of the material must have been there physically, too.

We were on a ton of locations, which is important. We wanted to shoot as much on location as possible and I think effects have gotten to a point now that sometimes you don’t even know it was green screen. Especially in contemporary modern movies, you have characters in a city and the city wasn’t there and you’re like, really? There was a lot of stuff here where they put a landscape behind someone and it was like, holy shit, I forgot we were on a green screen there. So location as much as possible, but for practical reasons, sometimes you have to shoot green screen and just know how to light so you look like you’re outside.

How do you go about blending the real people with all your digital monsters?

If you want effects to work, they have to interact with the world and the characters as much as possible, so what you’ll do is set charges on trees that’ll blow a tree up and then the animator has something to interact with and it’s always gonna look real. With the Chimera running through a village, you’re blowing up walls and stuff. And also, Sam is excellent at creating things. There’s a shot where the labyrinth is coming apart and reconfiguring, and Sam’s looking all over the place and that’s giving everyone cues to do things. If the actor’s not giving you that, it’ll never seem real. It’s a lot of how you light a scene. I like hard sunlight on CGI because it blows out the highlights. When you design a creature, make sure the textures you’re picking for them are textures that computers render well. That’s why Transformers looks so good, because steel and plastic is very easy to render with CGI whereas flesh and biological stuff is difficult. So it’s just a lot of making decisions to make your life easier.

Speaking of that labyrinth scene, you’ve got one shot during the reconfiguration where it looks like a piece of the set legitimately slid under Sam’s feet. Is that practical at all?

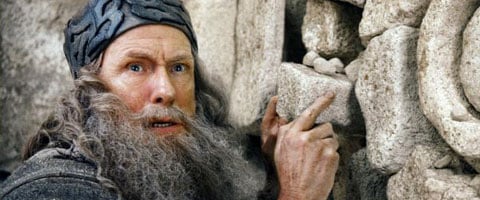

That’s CG. That’s all CG. That was what blew me away. You want to know the one which really blew me away was where Bill Nighy is doing that thing with the door [mimics motions of Nighy grabbing portions of the door], the door isn’t there and I was like, ‘Holy shit.’ That, to me, blew me away when I started seeing those dailies. He’s just doing this to green blocks and they rendered it so photo-realistically, I was like, holy shit, I should have made like a door monster or something. [Laughs]

How was it working with guys like Bill, Liam and Ralph? You’ve had great casts before, but these guys are some really heavy hitters.

Fantastic. These guys are incredible and you feel stupid directing them because they’ve been directed by like geniuses in genius movies and you feel not worthy and stupid, like you’re gonna fuck their career up.

Was there ever an awkward moment, like maybe the first day you were directing them, and you just didn’t know how to do it?

There’s always awkward moments, but, as the director, you must always pretend you know. Even when they go, ‘That’s a stupid idea,’ you’re like, ‘It’s a joke guys. Calm down. Did you think I’d really ask you to do that?’

Does that trick work on a set with hundreds of crewmembers and extras?

Always. Always works. ‘Guys I was just joking. Come on! We don’t have to do this,’ you know? [Laughs]

What’s the hope from here with this movie? I assume if all goes to plan, there’ll be round three.

I hope it makes some money!

Is there any option in your agreement to return?

No option in my agreement, but I hope it makes a lot of money and they want to keep going. That’s up to them, not to me.

Staff Writer for CinemaBlend.