10 Cool Frankenstein And Dracula Behind-The-Scene Facts About The Classic Horror Movies

We’re giving you some treats as Frankenstein and Dracula turn 90 this year.

Hope everyone has been enjoying Spook-tober or whatever we’re calling the build up to Halloween these days with some great horror films, but we need to devote some time to two of the original classic horror movies, Frankenstein and Dracula; the 1931 versions just to be clear. Each film is turning 90 this year, so what better time than now to learn some behind-the-scenes facts about the OG Hollywood movie monsters.

Tod Browning Wanted To Make Dracula In The 1920s, But Universal Turned Him Down

The 1931 film of Dracula is considered the first official, sanctioned version of Bram Stoker’s famous vampire appearing in a movie, but it is not the first film to be inspired by Stoker’s classic novel. F.W. Murnau’s Nosfertau in 1922 is the most famous example, but even before that there was reportedly a Hungarian film called Dracula’s Death in 1921, however prints of it are thought to be lost. However, Universal had the opportunity to beat both of them to the punch.

According to an essay by film historian Gary Rhodes for the Library of Congress on Dracula’s admittance into the National Film Registry, Tod Browning, who directed the 1931 Dracula, wanted to make the film as far back as 1920, but Universal founder Carl Laemmle Sr. turned him down; in fact he did so multiple times throughout the 1920s.

Browning would not get his green light for Dracula at Universal until the 1930s, when it was Carl Laemmle Jr. in charge, who was more of a fan of the macabre than his father.

Bela Lugosi Originally Played Dracula On Broadway, But Was Not First Choice For Film

Part of the reason that Universal finally came around on Dracula was because the vampire had become a massive hit on Broadway, thanks in part to the star of their production, Bela Lugosi. However, despite performing the role of Dracula hundreds of times on stage (with the Hungarian immigrant reportedly learning his lines phonetically at first), he almost was not Dracula on the big screen.

A Universal Studios made documentary titled The Road to Dracula, which was a bonus feature on a DVD release of Dracula, explains that the first choice to play the infamous vampire was Lon Chaney, who had starred in both The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925) for Universal. Chaney was known as “The Man of a Thousand Faces” because of the makeup that he himself would create for these classic movies. Tragically, Chaney’s Dracula would not come to be, as the actor died in 1930.

Of course, Lugosi would go on to don the cape for the film adaptation and create his own now iconic performance.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

Dracula Was Not Directly Adapted From Stoker’s Original Novel

Have you ever wondered why Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 telling of Dracula chose to refer to itself as Bram Stoker’s Dracula in essentially all of its promotional material? A big reason for that could be that it was actually one of the closest adaptations of the author’s original work, as the 1931 movie actually had another source it pulls from primarily.

Universal initially wanted to have a big, lavish production of Stoker’s work, but financial struggles (including the stock market crash in 1929) caused for a scale back of the story and for the studio to again look to Broadway, as TCM and The Road to Dracula detailed.

The play Dracula was originally produced in London with a script by Hamilton Deane and when it came over to the U.S. for its Broadway debut it added another writer, John L. Balderston (not just a coincidence with the last names, I am a relation). It was Deane and Balderston’s stage play that served as the primary source for the film adaptation. Garrett Fort, however, is the writer who receives primary credit for the final script.

Universal would actually follow the same playbook for Frankenstein months later, as a stage adaptation of Shelly’s story was also written by Balderston, though this time Fort and Francis Edward Faragoh were the credited screenwriters.

A Spanish-Language Version Of Dracula Was Made Simultaneously

In 1931, talking pictures were still very new and Hollywood was working out all of the kinks. One of those was how to create versions of Dracula for international markets when the process of dubbing wasn't in practice yet? To create a Dracula for Spanish-speaking audiences, Universal decided that it would simply create a separate production of Dracula spoken in Spanish, using the same sets but a Spanish-speaking cast.

This version of Dracula was directed by George Melford and starred Carlos Villarías as Dracula and Lupita Tovar as Eva. How the production would work, profiled in a piece from The Guardian, is the English version of Dracula would shoot in the mornings and the Spanish version would take over the set at night.

As film historian Lokke Heiss said in the documentary The Road to Dracula, this kind of gave Melford’s Dracula an advantage:

Apparently, what happened was the initial crew, Browning’s crew, would shoot these sequences. The second crew, the Spanish crew, would look at them and say to themselves. ‘We can do better than that.’ And they would go and they would do better.

Universal did not do separate productions for all of the foreign countries they sent Dracula out to, however. Instead, most international markets, or theaters not yet equipped for sound, got the English-language Dracula, but it was repurposed as a silent film.

Bela Lugosi Was The First Person Considered For The Role Of Frankenstein’s Monster

Dracula was a huge hit when it came out and Lugosi became a massive star for his performance, so Universal thought that they should ride the hot hand and have Lugosi play the key role in their next monster movie, Frankenstein.

Lugosi was not thrilled at the idea of playing the Monster, a part that he is quoted describing as worthy of “a half-wit extra,” in the book The Very Witching Time of Night: Dark Alleys of Classic Horror by Gregory William Mank. Lugosi would screen test for the role of the Monster, but ultimately the casting didn’t go forward.

Though there are rumors of other actors flirting with the part, Lugosi’s exit eventually led to the arrival of Boris Karloff as the Monster.

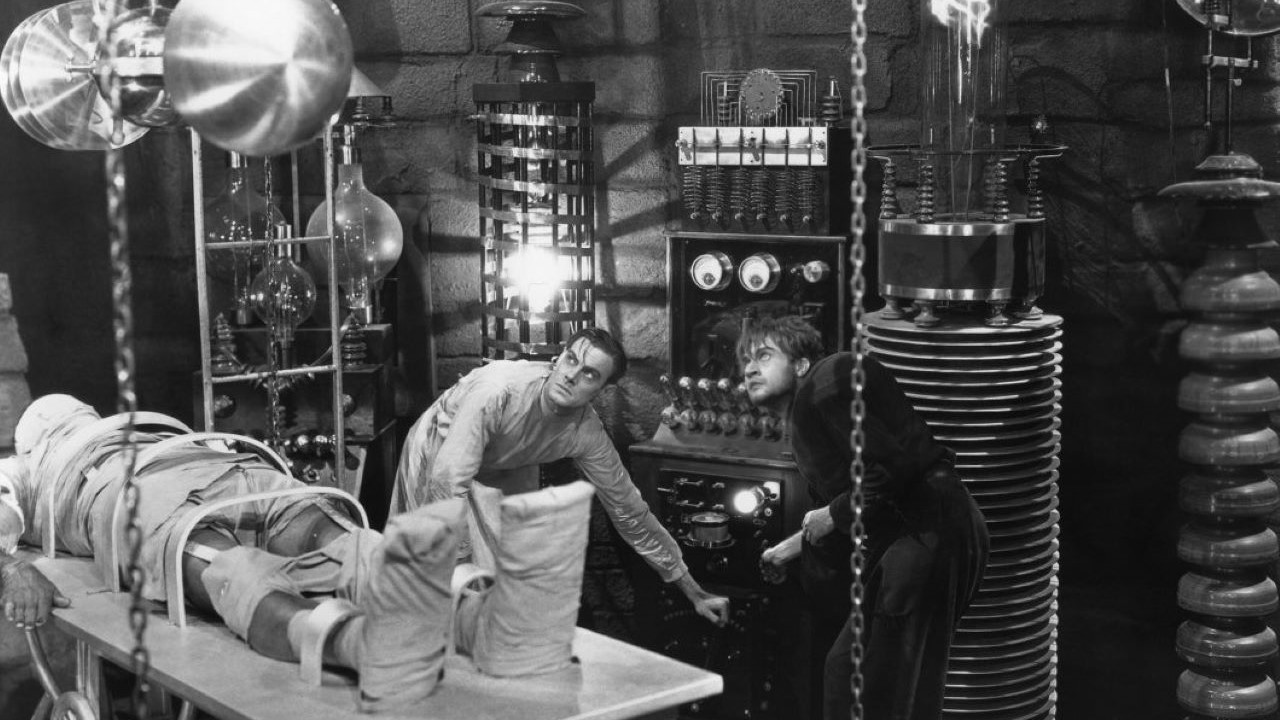

Lugosi would eventually play Frankenstein on the big screen, in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (see picture above).

Jack Pierce Was The Man Behind The Monster’s Look

The look of Frankenstein’s monster in the 1931 film has become the definitive image of the character, not least of all because Mary Shelly was not overly descriptive of the look in her novel. While Karloff’s unique features certainly played their part in, perhaps the man most responsible for what we know the monster to look like is make-up artist Jack Pierce.

A profile from American Cinematographer details that Pierce had worked on Dracula with Lugosi, though that make-up really just consisted of a light green tone to give him a bit of a ghoulish look. When Lugosi was still in consideration for Frankenstein’s monster, the star was averse to nearly all of the elaborate make-up ideas that Pierce had for the character.

Unlike with Lugosi, Pierce had a willing canvas in Karloff and together they created one of the most iconic faces of horror the big screen has ever known.

Frankenstein’s Laboratory Was Entirely A Creation Of The Movie

Much like how Mary Shelly didn’t provide too much about the monster in her book, the way that the monster was created was also left rather vague. But as with make-up artist Jack Pierce, the Frankenstein production had a creative mind that would craft an iconic Hollywood set from scratch.

This time the task fell to Kenneth Strickfaden, who as The Museum of Modern Art described in an article, was an inventor with a passion for electricity. In the 1920s he found himself working for many movie studios, including Universal. When it came time to create Frankenstein’s lab and bring it to life for the first time, director James Whale turned to Strickfaden. His creations included a large Tesla coil he dubbed the “Megavolt Senior,” along with the “Neutron Analyzer,” “Cosmic Ray Diffuser” and a “Baritron Generator.”

These machines became so much a part of the legacy of Frankenstein that Mel Brooks found Strickfaden and reused his equipment for his laboratory scene in his Frankenstein spoof, Young Frankenstein.

Frankenstein Faced Multiple Censorship Issues, Including Being Banned

Compared to horror films of today like Malignant or Halloween Kills, Frankenstein likely seems pretty tame, but it was anything but for audiences seeing it in 1931.

Turner Classic Movies cites in its notes on the film (from a file in the MPAA collection at the AMPAS library) some regional censorship agencies made cuts of the film before it could play before their local audiences, in some cases removing a close-up of a hypodermic needle or the dead body of the little girl the monster throws into the lake. Meanwhile, some countries banned it outright, including Northern Ireland, Sweden, Italy and Czechoslovakia.

The Hays Office, which oversaw censorship in the early days of Hollywood, told Universal in its report that it did have some concerns of “gruesome [scenes] that will certainly bring an audience reaction of horror.” The studio, either adhering to the Hays Office or as a gimmick, did include an introduction to the film warning audiences of what they are about to see.

However, things went further when Universal sought to re-release Frankenstein in 1937. The Hays Office had more power and was putting a tighter grip on Hollywood at that time and told Universal that in order for it to approve a re-release they would have to eliminate Frankenstein’s line where he says he now knows what it feels like to be God, shorten Fritz’s tormenting of the monster and eliminate the scene of the monster tossing the girl into the lake. Universal complied, but these scenes were added back into the film years later.

The Term ‘Horror Film’ Comes From The Press And Public Reaction To Dracula

The legacy of 1931’s Dracula and Frankenstein go beyond the actual films themselves (people go nuts over the original posters too). In fact it includes giving the horror genre its name, particularly Dracula.

In Gary Rhodes essay for the Library of Congress, he notes that Universal originally marketed Dracula as “The Story of the Strangest Passion the World Has Ever Known.” It was actually the critics and audiences that began describing Dracula as a “horror movie.” The film became a big hit and the descriptor stuck. So, officially, Dracula is the grandfather of all horror movies that followed.

Dracula is among the great movies that are available to stream for Peacock subscribers, as well as to rent on-demand. Frankenstein is available to rent on-demand.

D.C.-based cinephile. Will dabble in just about any movie genre, but passionate about discovering classic films/film history and tracking the Oscar race.