1917 Writer Explains Why World War I Movies Are So Rare

When you look back on the history of warfare at the movies, World War II has a clear cut advantage over World War I when it comes to the quantity of films that have adapted each conflict’s respective struggles. 1917 writer Krysty Wilson-Cairns knows this fact quite well, and in her opinion, the war is underserved in film, although they’re sidelined for some specific reasons.

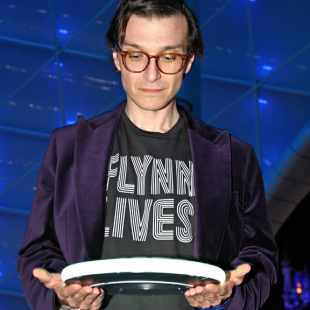

At the recent press day in London for the World War I epic she wrote alongside director/co-writer Sam Mendes, I asked Ms. Wilson-Cairns just why she felt this war in particular was at a disadvantage when it comes to cinematic output. In her opinion, the aspects that have held this specific niche of war history back are this combination of factors:

Here's the thing: it's usually compared against the second World War. [In] the Second World War, you've got very clear villains in the Nazis, just the worst people ever. You've also got movement throughout the land, whereas World War I was literally people entombed in trenches. Like buried six feet underground essentially, for three years, just lobbing munitions at each other and then trying to like move each other inches each way. So it's really hard to tell a dynamic story through that that isn't just trenches and mud.

As far as cinematic constructs go, it’s undeniable that a conflict that covers a wide scope of countries and battles makes for an easier well to go back to over the course of several decades of filmmaking. Not to mention, World War II took place during an era where the boom of cinema was just starting to take hold.

This saw the contemporary subject of WIII covered in films like The Best Years Of Our Lives, before being revisited throughout time with notables like The Longest Day, Saving Private Ryan, and more recently, Dunkirk. These iconic movies told tales of heroism from World War II’s theater of war.

That doesn’t mean that World War I is a subject less worth making into a feature film, but rather as Krysty Wilson-Cairns pointed out, it’s just going to be a more difficult undertaking. It's also important to mention notable films covering this period of warfare spanning from 1914 to 1918; as classics such as All Quiet On The Western Front and Lawrence of Arabia both cover the war to a certain extent.

However, there’s still a relative drought of content when it comes to this chapter in history, which meant that 1917’s writers would have to get creative with telling their story. Wilson-Cairns is a keen student of history, so an opportunity presented itself, allowing the film to build on one particular moment in time:

And the good thing about 1917 was we found a specific window of time, April 6, 1917, when a huge swath of land opened up where the Germans had disappeared one morning and had fallen back, and the English didn't know what was going on. You get to really play the confusion of warfare, the kind of madness of World War I, but you get to play it over a proper journey. And so you get a window into all of the war, rather than just trenches and mud.

As trench warfare and the limited scope of World War I’s area of operations may stymy a traditionally open narrative, director Sam Mendes’ real time/continuous take approach to 1917 probably made those conditions ideal to telling the story he was inspired to create with Krysty Wilson-Cairns.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

Tales from his grandfather Alfred’s service during World War I as a messenger were the initial catalyst for the journey embarked upon in 1917’s by Lance Corporals Blake and Schofield, played by Dean-Charles Chapman and George MacKay respectively. And after some initial growing pains and difficulties, a story was born, and a film could be made.

Of course, the story that Mendes and Wilson-Cairns had to work with needed to be an idea that not only fit into a World War I narrative, but also one that could change on the fly. Without the ability to film and use multiple takes in the editing process, as 1917’s continuous continuity wouldn’t allow such a practice, it was up to the writing team to make sure the film still made sense on a daily basis.

Much like the constraints of trench warfare, the real time journey of this film’s narrative provided very little room for the usual theatrical approaches that give the filmmaking team more room to breathe and find the film in the edit. So in a sense, World War I films like 1917 are not only historically difficult to make, but if you confine them to a scope as intimate and demanding as Sam Mendes’ continuous flow of action, they’re also technically and personally demanding as well.

However, that certainly hasn’t stopped Hollywood from starting to make World War I a sort of filmmaking trend in recent years. With director Peter Jackson’s documentary They Shall Not Grow Old, Dome Karukoski’s biopic Tolkien, and even Matthew Vaughn’s Kingsman prequel The King’s Man, it looks like audiences are about to get that much more familiar with a chapter of history that was previously deemed as the less cinematic of the two World Wars.

The end result of 1917 is surely going to lend to that effect, as the picture is already starting to rack up awards nominations, as well as the usual healthy buzz that will see it as a shoo-in come Oscar season.

But it’s important for anyone who wants to make a World War I movie like 1917 to realize that it is a much different beast than its more popular counterpart. Serving as the dawning of modern warfare, it’s not a battlefield the world at large is intimately familiar with, so certain care is needed when telling these sorts of stories.

1917 is currently in limited release, with the film’s wider release rollout planning to start on January 10th.

Mike Reyes is the Senior Movie Contributor at CinemaBlend, though that title’s more of a guideline really. Passionate about entertainment since grade school, the movies have always held a special place in his life, which explains his current occupation. Mike graduated from Drew University with a Bachelor’s Degree in Political Science, but swore off of running for public office a long time ago. Mike's expertise ranges from James Bond to everything Alita, making for a brilliantly eclectic resume. He fights for the user.