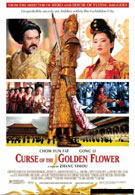

Like trying to fit a square peg into a smaller round hole, the pieces of Curse of the Golden Flower don’t seem to work together. The plot offers royal family deception and incest, yet is completely boring; the vivid colors and costumes are coupled with the computer-generated effects of a 10 year-old video game; and the grandiose set pieces are traversed via shaky, hand-held shots. When Chinese period-pieces are a dime a dozen, Curse of the Golden Flower hardly offers anything new or interesting.

The film’s story is made from the stuff that would make Shakespeare rise from his grave in copyright protest. Set in 10th century China, the Emperor’s first born son, Wan, is sleeping with his step mother, the Empress, and his half sister. Seeking revenge on his wife, the Emperor begins poisoning the Empress’ daily medicine in small doses. When the Empress receives word of this betrayal, she enlists the help of her royal guard-leading son to put an end to the Emperor. When all is revealed at the Chrysanthemum Festival, all hell breaks loose and the audience is treated to some much needed spectacle.

Perhaps it’s that the cultural relevance of the film doesn’t translate well with American audiences, leaving the Golden Flower feeling contrived and empty. For example, each Chinese hour (which equates to 2 western hours) is announced throughout the palace with a proverb and symbolic animal such as a rat, dragon, snake, monkey and so on. While these cultural symbols may be understood, they hardly resonate with the same power as the abundance of Christ imagery that is prevalent in American films, which would probably fall as flat with Chinese audiences. Similarly, we don’t feel the importance of the Chrysanthemum Festival because flowers are ornamental to us, while they carry the essence of life and prosperity with Chinese audiences.

Spectacle and violence however, is universal, and The Curse of the Golden Flower offers some of the most awe-inspiring visuals in contemporary cinema. The production value alone warrants the introduction of the film into American markets. The screen glistens with the vibrant reds, yellows and oranges and deep blues and greens and each set piece and costume is developed down to the deepest detail of texture. However, director Yimou Zhang decided to showcase the lavish sets and costumes with hand-held camera shots that pull you out of the time period and remind you of the flaws of contemporary filmmaking. In telling a classical story, it would be more appropriate to use more classic techniques, rather than inserting insulting C.G. shots of sword blades scraping across armor during fight scenes.

Speaking of fight scenes, the film’s climax offers a stunning display of what could have been an epic battle that made up for the hour and a half of cinematography misdirection and a slow, uninteresting plot. As thousands of the Empress’ troops storm the castle, they are met by 10 times as many of the Emperor’s troops, in siege towers no less. Unfortunately, the sequence features distracting C.G. effects that evoke the cut scenes of an Age of Empires video game rather than the stunning battles of Return of the King. Perhaps the film falls victim to the curse of the Lord of the Rings series, which set a new bar for set-piece spectacles.

Slow and pointless story aside, Curse of the Golden Flower half succeeds in its visual display, which sustains the audience for the first 20 minutes. The high production value provides a glimmer of hope that Zhang would pull off the much anticipated Chrysanthemum Festival climax, but Zhang remains consistently mislead in his direction and the climax fizzles with the “pop” of a bottle rocket, rather than the “boom” of a cannon.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News