“You will not like me,” claims the Earl of Rochester at the onset of the film. He claims the women will hate him because he’s a womanizer and the men will hate him because he’s better in the sack than they are. In actuality, you’ll may end up dismissing those boasts because he’s such a tragic figure. The people you won’t like are those responsible for bringing his story to the screen, mostly for the mind numbing, life draining way they go about doing it.

The Earl, John Wilmot by name, was the antithesis of the role model. A sort of Restoration Era “wild one”, his answer to the question “Against what rebelest thou, Johnny” would most certainly have been “What hast thou got?” Constantly drunk and a notorious philanderer, his final years were a race to see which he could wear out first: his liver or his genitals. The genitals won (or lost, depending on how you look at it) and he succumbed at the age of 33 to a nasty case of syphilis.

The film is far too piercing to be a simple biopic, but with a meandering storyline and an odd mix of dark humor, social commentary and stylized drama it’s hard to tell just what story the filmmakers are trying to tell. The movie centers on the idea that despite his exterior of sexual bravado the Earl was actually a man with the mother of all inferiority complexes. At the same time, the film incorporates the Earl’s risqué poetry, which didn’t become popular until decades after his death. Perhaps it’s an homage to the man’s connections with his hedonistic society and the literary inspirations those connections provided. Whatever the points of the film may actually be, they are quickly and constantly lost in all the heightened language and burdensome debauchery.

The filmmakers also go to extraordinary lengths to show how out of control 1600’s London actually was and how Wilmot fit into that picture. The city had attained the rank of Sodom and Gomorrah with its citizens paying a high price for their indulgences. The Earl of Rochester writes and produces a satirical play about England’s royal leaders, a show so bizarre that it incorporates midgets riding around stage on a giant phallus. That sort of scene is better suited to a Deuce Bigalow film, but Rob Schneider has nothing on the Earl. He was a rebel of the first order and his writings and actions reflect his edgy comfort in the runaway society.

To its credit the movie features some rather extensively and beautifully designed period sets and costumes but the ability to see them is butchered at the hands of a merciless cinematographer. Throughout the show the image is dark, grainy, shaky and out of focus. The effect is fine for the first ten minutes until a dull pain in the back of your strained eye sockets begins to set in. I’m sure it was done with some kind of artistic intention in mind but it doesn’t do any good to be artsy if it makes your film physically painful to watch.

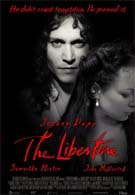

Amidst The Libertine’s many debacles shines it’s one bright spot: the cast. Johnny Depp tackles the character of The Earl with gusto, though at times he drifts into the eccentricities of Jack Sparrow and the sullenness of Gilbert Grape. Samantha Morton and Rosamund Pike, who play the Earl’s mistress and wife respectively, turn in some of their best dramatic work to date. John Malkovich is all but unrecognizable as King Charles II and unfortunately most of his understated performance is upstaged by his very large, very distracting prosthetic nose.

Sadly, the movie is most successful at giving the audience a firsthand sense of Wilmot’s experience as a terminal syphilis sufferer. We too are forced to endure some symptoms of the disease in full blown progression. Early on it’s simply a mild headache but as things progress the stir-craziness and insanity set in. Like Wilmot might have, I found myself pleading for it all just to come to an end. When the movie is done it really doesn’t matter whether we agree that we like the Earl or not. We can all agree on liking that the movie is over.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News