Interviews

CinemaBlend frequently sits down with the talent who are responsible for the movies, television shows, streaming features, and pop-culture moments that you want to be reading more about. From Tom Hanks to the cast of Avatar: The Way of Water, from the latest contestant on The Masked Singer to the cast of Yellowstone, CinemaBlend ample time for exclusive conversations with Hollywood's biggest stars.

And CinemaBlend prides itself on asking talent the questions that they aren't hearing from every other outlet, leading to passionate answers that are meant to educate and entertain you, our readers. If they are important in Hollywood, they are speaking with CinemaBlend.

Latest about Interviews

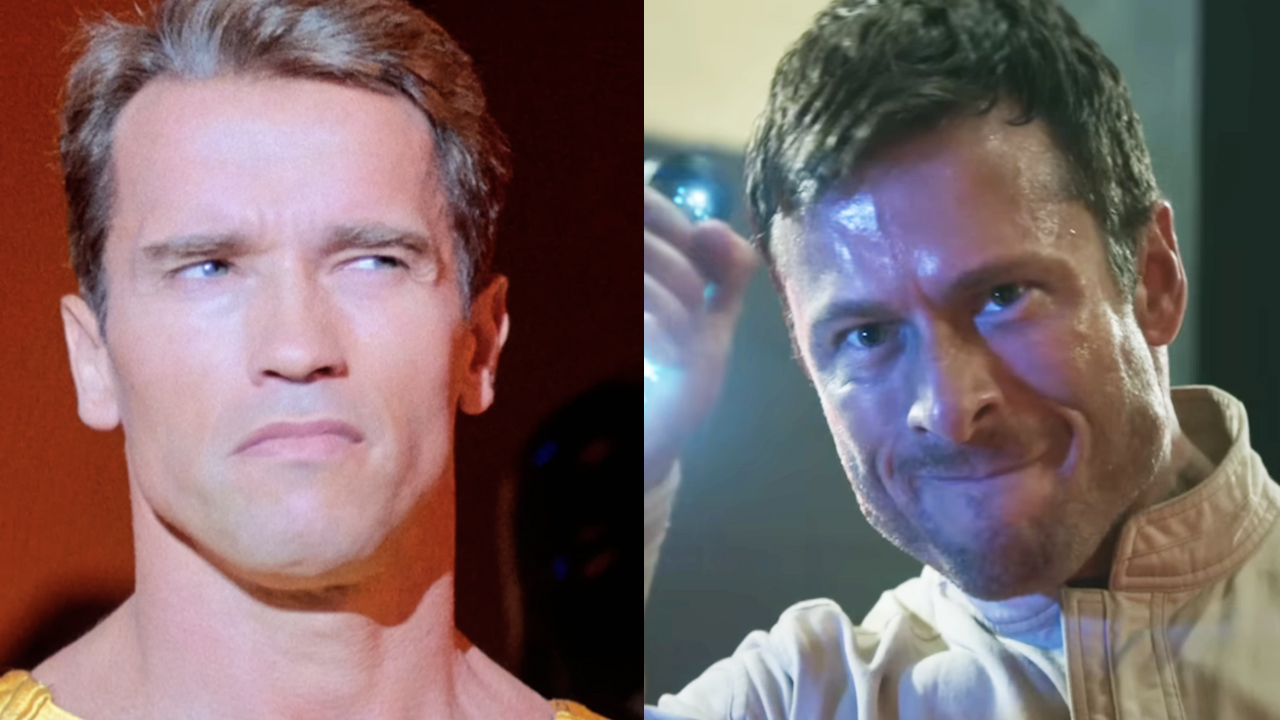

I Wasn't Expecting The Running Man To Parody The Kardashians. We Asked Edgar Wright About How It Came About

By Sarah El-Mahmoud published

Exclusives Yes, you can find reality TV in Stephen King's dystopia, too.

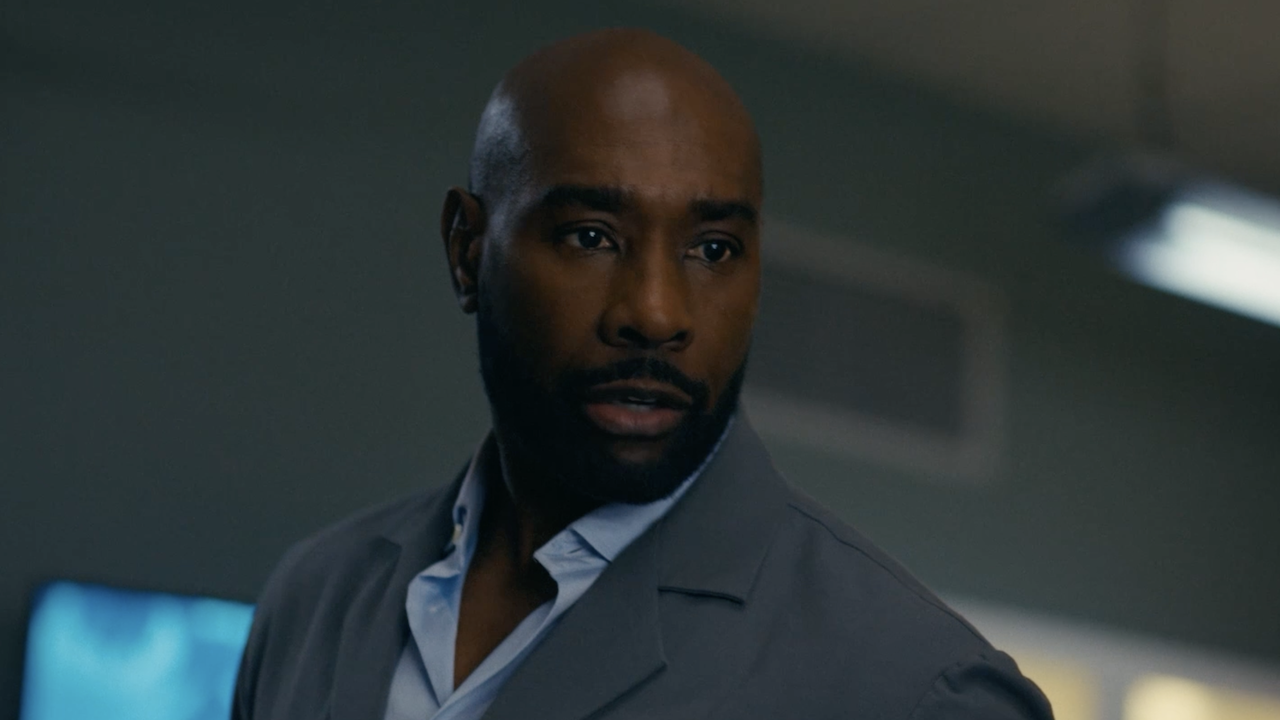

Watson Puts Himself On The Line For A Patient In Exclusive Clip, And It Fits With Morris Chestnut's Comments About Doing ‘Two Shows In One’

By Laura Hurley published

Exclusives The stakes are sky-high for John this week.

Adam Sandler Says A Joke He Made On Howard Stern Keeps Following Him Around

By Erik Swann published

Exclusives This one gag just won't go away.

Predator: Badlands’ Director Has Had Discussions About Female Yautja, But He Explains Why They Aren’t In The New Movie

By Eric Eisenberg published

Exclusives But perhaps in the near future...

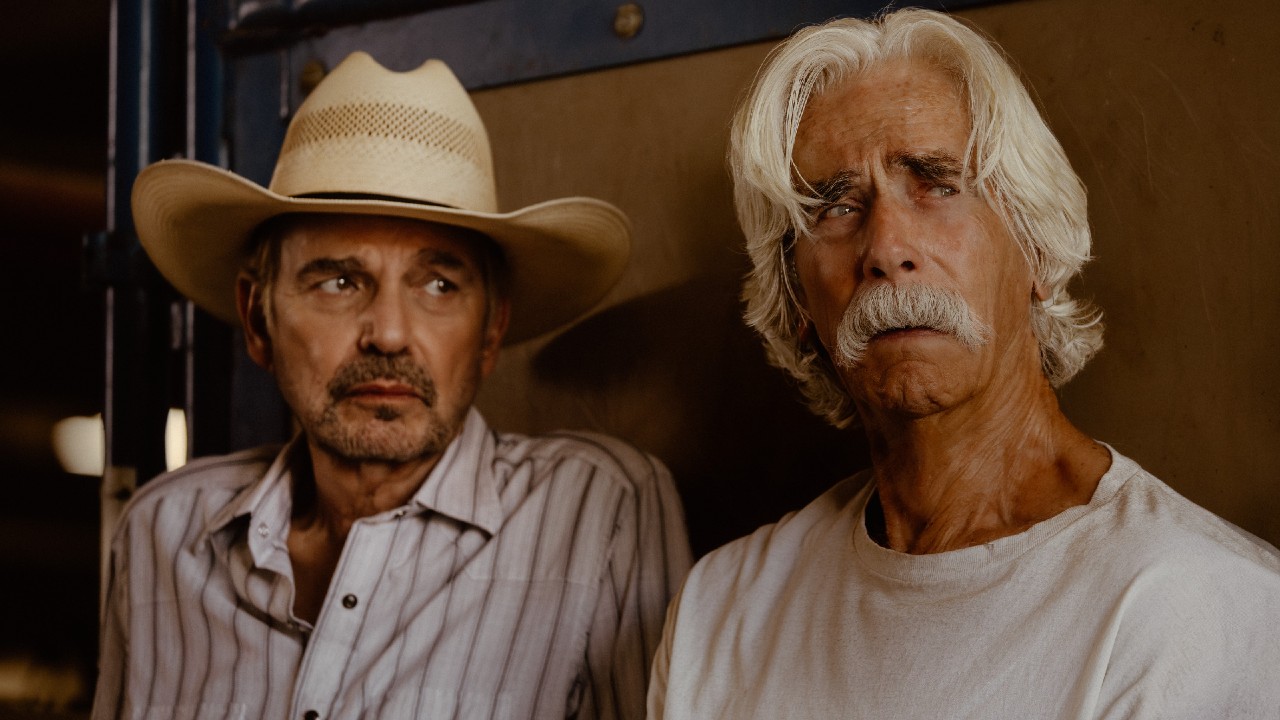

I Can’t Get Over The Amazing Way Billy Bob Thornton Reacted To Sam Elliott Playing His Dad In Landman: ‘This Is No Joke, And It’s Kind Of Embarrassing’

By Riley Utley published

Exclusives An appropriate reaction, I'd say.

NCIS's Roma Maffia Returned To The Show After 12 Years. Would She Do More With Vera Strickland?

By Adam Holmes published

Exclusives What are the chances we see her again?

The In Your Dreams Ending Twist Meant A Lot To Me, And The Director Told Me The Story Behind It

By Sarah El-Mahmoud published

Exclusives Alex Woo talks nightmares.

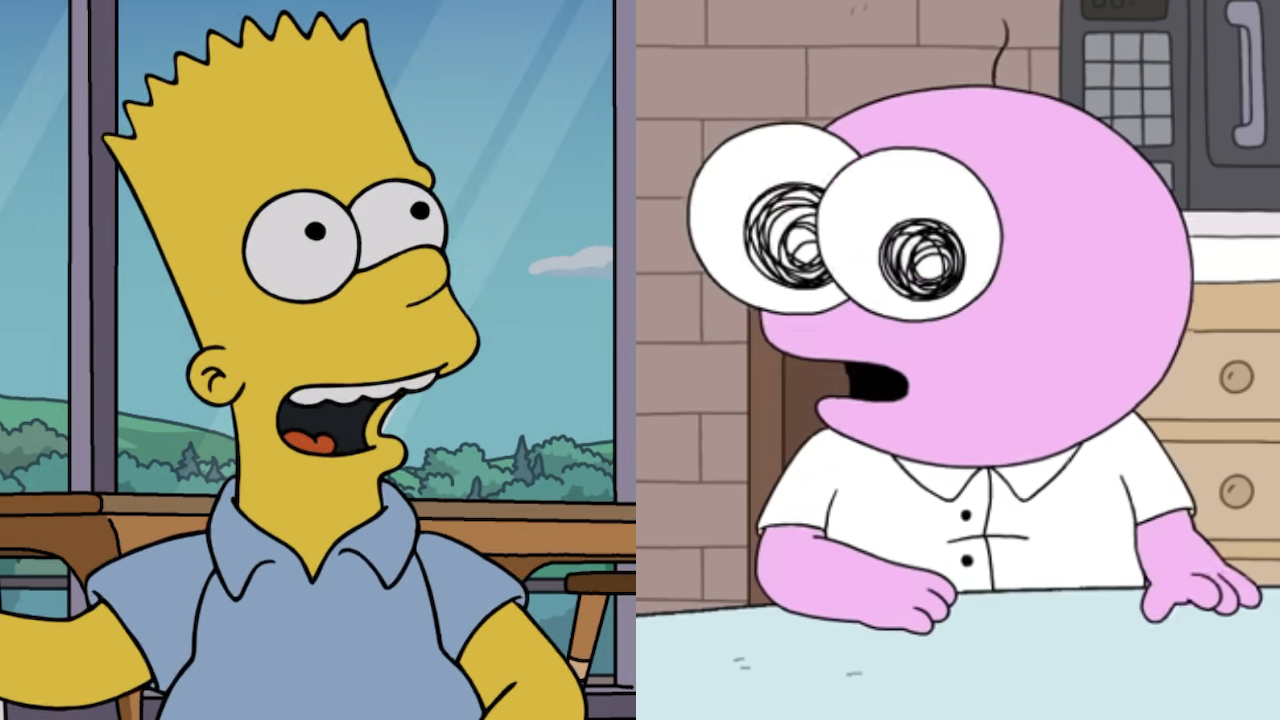

I Want To See A Gen V Season 3 If Not Just So The Show Can Try And Top That Ultra Disgusting Reveal In The Season 2 Finale

By Eric Eisenberg published

Exclusives It's a moment that will be hard to beat in terms of sheer nasty.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News