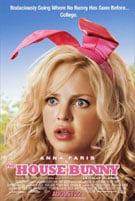

There’s nothing particularly original in The House Bunny, except perhaps for the sex of its stars. Karen Lutz and Kristen Smith’s script takes the standard college nerds make good formula, and replaces the usual slate of disgusting male dorks with girls who don’t use deodorant. It’s Revenge of the Nerds meets Legally Blonde, only without most of the things that made either of those movies fun. Instead, The House Bunny has cleavage, or the approximation of cleavage on the pumped up for screen, but probably not that well endowed Anna Faris, who muddles her way through yet another dead end comedy project.

Faris is Shelley, a Playboy Bunny who loves her life as a nookie girl at Hef’s shockingly PG mansion, but finds herself unceremoniously kicked out of the house when she turns 27 and is deemed too old to remain in residence. Lost and alone, Shelley wanders onto a college campus, where she discovers sorority houses and instantly (and perhaps correctly) identifies them as “mini-playboy mansions”. If she can’t have the real thing, Shelley will settle for a miniature version and soon she’s talked her way into playing house mother to the campus’s biggest bunch of loser girls, the Zetas.

The Zetas hire Shelley because they’re in trouble. They have to get thirty new pledges, or their sorority will be dissolved and they’ll be kicked out of the house. Since they’re a collection of misfits, no one wants to join. Luckily, being popular is Shelley’s specialty, and she jumps feet first into the task of making them pretty and interesting to boys. This is accomplished via a montage in which they all go shopping and buy bright clothes. There’s nothing more to it really. They all start wearing peach, and suddenly everyone on campus treats them as if they’re supermodels in training. A similar montage is used later on, when Shelley decides she wants to be smart, and becomes so after a music sequence in which she carries around stacks of books and scribbles notes on things. If only I’d known it was so easy, just think of all those years in community college I wasted studying. Who am I kidding. It was community college. Nobody studies.

The movie’s strength is not its script, which approaches the idea of telling a compelling story pretty casually. The House Bunny knows from the outset its plot isn’t very interesting, since it’s a plot you’ve seen dozens of times before in dozens of other movies. No, what makes it mostly bearable are some of the film’s performances. Emma Stone, whom you might recognize as Jonah Hill’s love interest from Superbad, plays Natalie, the head of Zeta’s nerd patrol. She’s cute, sweet, and funny. All the things you’d want in an awkward girl turns Cinderella story. She’s backed up by Kat Dennings, who I’ve always thought of as Scarlett Johansson without the benefit of exercise and sunlight, though you’ll probably recognize her as Catherine Keener’s step-daughter from The 40 Year-Old Virgin. They succeed, in spite of the movie’s somewhat banal setting, in turning in something relatively pleasant and appealing. And I guess I have to give some credit here to Anna Faris, who takes a thankless, empty-headed character in Shelley and manages, I suppose, to make her somewhat endearing and occasionally, even chuckle-worthy.

It is somewhat disturbing though that the movie never completely turns away from the idea that girls must be dumb and pretty in order to have any value in society. You expect The House Bunny to pursue that at first, as Shelley moves in and starts giving her Zetas makeovers. There is a somewhat half-hearted attempt by the kids towards the end of the movie, to salvage some of their personality before they turn into mindless fembots. But even as they consider a return to having brains, Dennings’ Mona character, previously the most independent of the bunch asks, “can we stay 60% Shelley?” The movie ends with its formerly smart, non-conformist girls deciding to remain at least 60% vapid bimbo. Who can blame them, when the only time they’ve been happy is when they’re shoving their breasts in the face of some drunken college frat boy who will probably rape them as soon as someone turns off the camera? House Bunny attempts to blunt this by having Shelley go after a guy who’s interested in girls with a brain, but it’s presented as if he’s some weirdo exception to the notion that men only care about tits and ass. Maybe The House Bunny has it right and all of life’s problems truly can be solved by shopping for brightly colored, slutty clothes. I’m just not sure I want to live in that world.

Final note: For any viewer awake enough to pick up on the idea that The House Bunny thinks everything will be alright if you just buy a halter top, the movie attempts to cheer you up with one of those horrible, shoe-horned in, end credits cast song and dance numbers. In this case they’re rapping, dancing, and singing; so it’s sort of a trifecta. This is one of the most annoying new trends in comedy filmmaking. It works when it serves a purpose, for instance in The 40 Year-Old Virgin when Steve Carell’s character goes Bollywood as a metaphor for finally having sex, but most of the time it has nothing to do with the movie and it’s been tacked onto the end because some studio executive heard a lot of people watch So You Think You Can Dance. You know a movie’s bad when there’s nonsensical dancing during the final credits. It’s like the Beverly Hillbillies waving goodbye at the end of each episode, only with Granny in a t-back and Jethro flashing gang signs at the audience as a way of saying thank-ya for watching, now go fuck yourself. Hey Hollywood, it really needs to stop.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News