Movies

Latest about Movies

-

-

Fast And Furious 11 Details Are Being Kept ‘Under Wraps,’ But An Exec Confirmed A Major Promise Vin Diesel Made

By Eric Eisenberg Published -

‘You Look So Pretty.’ See The Moment A Sheerly Stunning Gwyneth Paltrow Ran Into Fellow Awards Contender Kate Hudson

By Heidi Venable Published -

Bond, James Bond: All 8 Actors Who Played 007, From 1954 To Present

By Mike Reyes Last updated -

Legendary Actor Robert Duvall Has Died At The Age Of 95

By Eric Eisenberg Published -

How An Aimee Lou Wood Play In London Just Led To Some Brand New James Bond Gossip

By Ryan LaBee Published -

Crime 101 Is About 30 Minutes Too Long, And There Was Such A Simple Way To Shorten It

By Hugh Scott Published -

Bill Murray Confirms He Really Did Get ‘Bitten Twice’ During Groundhog Day, And The Backstory Is Wild

By Mack Rawden Published

-

Explore Movies

Box Office

-

-

One Of The Biggest Box Office Weekends Of 2026 Sees Wuthering Heights Dominate For Valentine's Day

By Eric Eisenberg Published -

Send Help Survives At Number One With Solid Numbers On A Slow Box Office Weekend

By Eric Eisenberg Published -

Send Help Wins The Box Office With The Biggest Weekend Of 2026 So Far, But It Had Some Surprising Competition

By Eric Eisenberg Published -

Avatar: Fire And Ash Falls From The Top Of The Weekend Box Office As Mercy Takes #1

By Eric Eisenberg Published -

Will 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple Take Down Avatar: Fire And Ash At The Weekend Box Office? It's Going To Be A Photo Finish

By Eric Eisenberg Published -

Primate And Greenland 2 Prove Light Competition For Avatar: Fire And Ash At The Weekend Box Office

By Eric Eisenberg Published -

First Box Office Weekend Of 2026 Delivers Milestones For Avatar: Fire And Ash And The Housemaid

By Eric Eisenberg Published -

It's Christmas On Pandora As Avatar: Fire And Ash Has A Massive Second Weekend At The Box Office

By Eric Eisenberg Published -

Avatar: Fire And Ash Rules The Weekend Box Office (Duh), But Questions Linger About The Future

By Eric Eisenberg Published

-

Features

-

-

Bond, James Bond: All 8 Actors Who Played 007, From 1954 To Present

By Mike Reyes Last updated -

Johnny Depp And Amber Heard: A Timeline Of Their Professional And Personal Relationship

By Philip Sledge Last updated -

Steven Spielberg Is Now An EGOT Winner, Joining The List Of Celebrities To Earn An Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, And Tony Award

By Jerrica Tisdale Last updated -

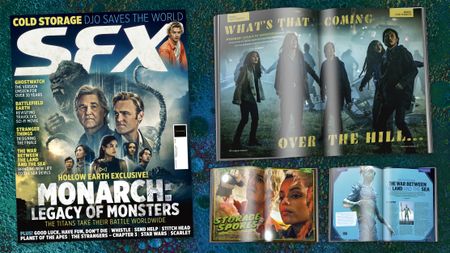

New Issue

New IssueBrace For Titan Action In Monarch: Legacy Of Monsters With The Latest Issue Of SFX

By SFX Published -

Upcoming Star Wars Movies And TV Shows

By Eric Eisenberg Last updated -

Upcoming Video Game Movies And Shows I Can’t Wait To See In 2026 And Beyond – Super Mario Galaxy, Mortal Kombat II, And More

By Philip Sledge Last updated -

Upcoming Horror Movies: All The New Scary Movies Coming Out In 2026 And Beyond

By Sarah El-Mahmoud Last updated -

Upcoming Book-To-Screen Adaptations: What To Read Before The Movie Or TV Show

By Sarah El-Mahmoud Last updated -

I Just Found Out One Battle After Another's Chase Infiniti Has 2 Upcoming Roles, And I'm Really Excited About It

By Sarah El-Mahmoud Published

-

More about Movies

-

-

Bill Murray Confirms He Really Did Get ‘Bitten Twice’ During Groundhog Day, And The Backstory Is Wild

By Mack Rawden Published -

Someone Finally Asked Cynthia Erivo About The Rumor She And Ariana Grande Were Lovers On Wicked

By Ryan LaBee Published -

James Van Der Beek’s Rep Spoke Out After Backlash Over Home Purchase And GoFundMe

By Jessica Rawden Published

-